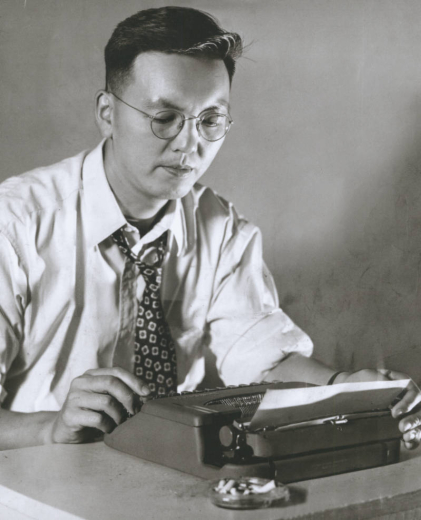

Author, Denver Post editor, and diplomat who worked to promote the rights of Japanese Americans and improve U.S./Japan relations after World War II.

Kumpei Hosokawa was born in Seattle, Washington, in 1915. Kumpei's parents moved to the United States from Japan when they were teenagers. His mother was a teacher, and his father ran an employment agency for Japanese immigrants.

Although his parents had good jobs, the Hosokawa family lived in a tiny apartment in Seattle's very poor Japantown. This was because in the early 1900s, the United States had laws preventing Asian Americans from owning property or living in white neighborhoods.

Kumpei's parents both spoke English, but only ever spoke Japanese with their children so they would not learn to speak English with Japanese accents.

The Hosokawas decided to rename their son William (Bill for short) when he was five years old. They wanted him to have a name that would be easy for American teachers to pronounce.

The first few years of school were very hard for Bill. Since he only spoke Japanese, he fell behind the rest of his English-speaking class. However, he eventually learned English so well that he almost completely forgot his first language.

Bill wouldn't become fluent in Japanese again until he was in his twenties.

After high school, Bill went to the University of Washington to study Journalism. He wanted to become a writer for newspapers. He was the first person in his family to go to college.

When Bill was in his third year of college, a Journalism professor pulled him aside for a meeting. The professor told Bill he should change his major to something stereotypically Asian, like math or engineering. The professor claimed white Americans would accept Asian Americans in those fields, but "no newspaper in the country would hire a Japanese boy."

Bill did not let that conversation keep him from graduating with a degree in Journalism. Unfortunately, the professor's warning turned out to be true - no newspapers wanted Bill to write for them.

Bill took a job writing speeches for the Japanese consul in Seattle instead. Through his job at the consulate, Bill found out that a Japanese businessman was starting an English-language newspaper in Singapore. This new newspaper, the Singapore Herald, was looking for an editor trained in American-style journalism.

Bill was twenty-five and had just gotten engaged. Bill did not want to leave the United States, but he knew his chances of getting a journalism job were much better in Asia. Bill applied for and was offered a job at the Singapore Herald. He and his fiancée, Alice, had a quick wedding before moving to Singapore.

The Hosokawas had been in Singapore for a year and a half when Alice became pregnant with their first child. She decided to return to the United States to be with family. After Alice left for the United States, Bill took a reporter position at the Shanghai Times in China.

His job was to write about the Nazis in Asia, and Japanese attempts to expand into China.

After a year, Bill realized that living in China as a Japanese American was getting too dangerous. Many anti-Japanese riots broke out, and Bill decided to return to the United States, as well.

He arrived in Seattle in October of 1941.

As Bill himself said in later years, his timing could not have been worse.

On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked the U.S. Naval Base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Bill was horrified by this event, and volunteered to join the United States Army. He was rejected.

Overnight, Japanese Americans were seen as enemies. Bill helped create an Emergency Defense Council for the Japanese American Citizen's League in Seattle. He wanted to make sure the United States government would not retaliate against Japanese Americans.

Seattle city officials promised the Japanese American Citizen's League that Japanese Americans would not be targeted by the government.

However, in February 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. This order called for the "evacuation" of 122,000 Japanese Americans, 11,000 German Americans, and 3,000 Italian Americans who lived on the West Coast.

These people were deemed to be national security risks to the United States and moved into incarceration camps. Because Bill had worked for the Japanese consul and written for Japanese-owned newspapers, the Hosokawas were among the first families ordered to report to a camp.

The camp was not finished yet so Bill, Alice, and their one-year-old son, Michael, were held at a fairground outside of Seattle with 7,000 other detainees. The Hosokawas had to live in a horse stall for three months until they were sent to an interment camp in Heart Mountain, Wyoming.

After being sent to Heart Mountain, Bill once again volunteered to join the United States Army, and was once again rejected.

Bill became the editor of the Heart Mountain Sentinel, the newspaper for prisoners of the camp. He taught classes to Japanese American prisoners who did not speak or write English well.

The Hosokawas were at Heart Mountain for a little over a year. Because so many men were at war, prisoners could petition to be released from incarceration camps (under supervision) to do jobs that were left unfilled. Bill was able to use his journalism experience to get a job as a copy editor at the Des Moines Register. The Hosokawas were released and sent to Iowa.

Even though Bill was not in an interment camp for the entire War, he never forgot how Americans could imprison their own people out of racism and fear.

After the end of the War in 1945, Bill began looking for another journalism job.

He learned that the Denver Post was hiring writers and editors. Bill did not want to apply for these jobs because the Denver Post was well known as one of the country's most anti-Japanese newspapers. They published many untrue stories that turned popular opinion against Japanese Americans during World War II.

In 1946, the Denver Post got a new editor-in-chief from Oregon. His name was Palmer Hoyt, and he wanted to change the Denver Post's reputation to become a more serious and progressive newspaper. Bill decided to apply to the Denver Post after this, and was hired as a copy editor.

Bill worked in various writing and editing positions at the Denver Post. He helped Palmer Hoyt establish the Sunday magazine for the Denver Post, the Rocky Mountain Empire. The Empire focused on cultural events in the Denver and Colorado region. Palmer Hoyt made Bill the editor of the Empire, and Bill wrote many of the columns for the magazine, as well.

After Bill became the editor of the Rocky Mountain Empire, he and Alice wanted to move their growing family to a larger house in a less expensive neighborhood. They decided on Park Hill, a white neighborhood in segregated Denver.

Bill and Alice soon found that no real estate agents would sell them a house. At the time, real estate companies did not allow agents to sell non-whites a house in a white neighborhood. The Hosokawas finally found someone who was willing to sell them a home privately. However, when they moved into the neighborhood, many Park Hill residents protested that the neighborhood would no longer be fully white.

In response, fifty of Bill's white Denver Post coworkers held a barbecue at the Hosokawa house to show their support for Bill and his family. The Hosokawas did not have any more trouble with the neighbors after this. In his autobiography, Bill wondered if Japanese Americans could have been kept out of incarceration camps if their white friends had shown similar support.

Bill served as a war correspondent for the Denver Post during the Korean and Vietnam Wars. This was because of Bill's previous experience living in Asia, and because the Denver Post thought an Asian American reporter would attract less notice than a white reporter in Asian countries. He reported from Asia frequently, and was nominated for the 1961 Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of student riots in Japan.

Bill became the assistant managing editor of the Denver Post, making him the highest-ranking Asian American in journalism for many years.

Bill remained active in the Japanese American community throughout his life. He served as an executive member of the Japanese American Citizen's League, and was always willing to help new Asian immigrants.

Bill wrote eleven books on the history of Japanese Americans in the United States. His most famous book, Nisei: The Quiet Americans, was published in 1969.

The Quiet Americans documented the experience of second-generation Japanese Americans (called Nisei), including their imprisonment in incarceration camps. The 1960s and 1970s were a time when many minority groups worked for a greater voice and more influence in America. Because of this, The Quiet Americans was very controversial. Some people thought it glorified Japanese Americans for not fighting arrest and incarceration during World War II. However, The Quiet Americans was the first major book published on Japanese American history, and it inspired many people to look more closely at Japanese American life and culture.

Bill also wrote a weekly column for the Japanese American Citizen's League newspaper, called the Pacific Citizen. The column was titled "From the Frying Pan," and discussed Japanese Americans readjusting to life after incarceration. Bill wrote "From the Frying Pan" starting in 1945, and continued throughout his life. It encouraged Japanese Americans to see things like intolerance and prejudice through a lens of humor instead of anger.

Because of Bill's prominence in the Japanese American community, in 1976 he was asked to become the honorary Japanese consul for the Western states. Bill used this position to help rebuild relationships between the United States and Japan.

In 1984, Bill left the Denver Post to become the reader ombudsman for the Rocky Mountain News. He wanted to spend less time editing, and more time helping people. In 1986, Bill became a lecturer at Denver University specializing in Asian Affairs, and helped create an exchange program for American and Japanese students. He dedicated himself to his work as Japanese consul, a position he held until 1999. Bill was one of the chief consultants for the Washington, D.C. Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism During World War II, and some of his writings are carved on the memorial.

Bill traveled around the country giving speeches on the dangers of racism. He spoke out against anti-Muslim backlash following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in the United States. Bill wanted to make sure that all people were treated equally, regardless of their race.

In 2003, Bill was honored with the lifetime achievement award from the Asian American Journalists Association. In 2007, the Anti-Defamation League presented Bill with their annual Civil Rights Award.

Bill passed away later that year, at the age of ninety-two.

Two identical memorials to Bill Hosokawa stand at the Denver Public Library and in the Bill Hosokawa Bonsai Pavillion at the Denver Botanic Gardens. They were dedicated in 2012.

employment agency – a business that helps people find jobs

fluent – able to speak, read, and write a language easily and accurately

stereotypical – an exaggerated or oversimplified generalization of a group

consul – a person appointed by a government to move to a foreign city and assist the citizens of their home country living abroad

consulate – the building and employees that support a consul

retaliate – to make an attack in return for an earlier attack

Executive Order 9066 – the “evacuation” of people of mostly Japanese descent, but also German and Italian, from the West Coast to forced camps further inland following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, by Japan. The majority of Japanese Americans in Hawaii were not sent to incarceration camps, though Japanese Americans were 40% of Hawaii’s population.

incarceration camps – a prison or detention center used for civilians in wartime

detainees – people held in custody for political reasons

copy editor – a person whose job is to improve the formatting, wording, and accuracy of an article

segregation – the enforced separation of different racial groups

war correspondent – a journalist reporting from a scene of war

controversial – something that inspires public debate and differing opinions

prejudice – an unfavorable opinion formed without knowledge or reason

prominence – leading, important, or well-known

ombudsman – someone who investigates and resolves complaints in an impartial way

backlash – a widespread negative, sometimes violent reaction to an event

Have you ever seen someone treated badly because of their race? What did you do? Would you do anything differently?

People in the United States were very afraid of Japanese Americans during World War II. Do you see anything similar in the United States today?

Imagine you are a newspaper writer. What would you write about?

Why do you think Bill Hosokawa wrote so many books on the history of Japanese Americans?

Bill Hosokawa Manuscript Collection (Primary sources including photographs, letters, book drafts and articles by and about Bill Hosokawa. The Bill Hosokawa manuscript collection can be viewed in person on the 5th floor of the DPL Central Library.)

Biography Clipping Files (Newspaper and magazine articles, including obituaries, about Bill Hosokawa that can be seen in person on the 5th floor of the DPL Central Library)

Bill Hosokawa in the Denver Public Library Digital Collections

Books by Bill Hosokawa at the Denver Public Library:

- The Uranium Age (talks about the creation of nuclear weapons and the relationship between the US and Japan)

- The Two Worlds of Jim Yoshida (a biography of a Japanese American stranded in Japan at the outbreak of WWII and drafted into the Japanese army. IN JAPANESE)

- Thunder in the Rockies: The Incredible Denver Post (a history of the Denver Post, with biographies of its writers, editors, and publishers)

- Nisei: The Quiet Americans (Bill Hosokawa's most famous and most controversial book)

- They Call Me Moses Masaoka (written with Mike Masaoka, a biography of the complicated Japanese American civil rights leader)

- JACL: In Quest of Justice (a history of the Japanese American Citizen's League)

- Old Man Thunder, Father of the Bullet Train (a biography of Shinji Sogo, the Japanese railroad executive who created the high-speed bullet trains of the 1960s)

- Colorado's Japanese Americans: From 1886 to the Present (a comprehensive history of Colorado's Japanese American population)

- East to America: A History of the Japanese in the United States (co-written with Asian Literature scholar Rob Wilson)

- Thirty Five Years in the Frying Pan (Bill Hosokawa's autobiography, includes many of his "From the Frying Pan" articles on post-incarceration life for Japanese Americans)

Books about Bill Hosokawa at the Denver Public Library:

- Bill Hosokawa: Journalist (part of the Great Lives in Colorado History series. Perfect for 3rd to 5th grade readers. In English and Spanish)

Biography of Bill Hosokawa from the Densho Encyclopedia

Photographs of Bill Hosokawa and Family from the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley (most are from the Hosokawas incarceratio at Heart Mountain)

Transcript of Interview with Bill Hosokawa by former Wyoming State Historian Mike Junge

Video of Interview with Bill Hosokawa at Discover Nikkei (a website for Japanese migrants and their descendants)

He went to University of

He went to University of Washington

He was an amazing student he

He was an amazing student he stayed 2 hours at school after it ended.

Add new comment