York and his contributions to the success of the Lewis and Clark Expedition is not a well known part of American history. When retelling the story of the expedition, historians rarely mention him or recognize him as an explorer who was instrumental in helping map areas of the western United States.

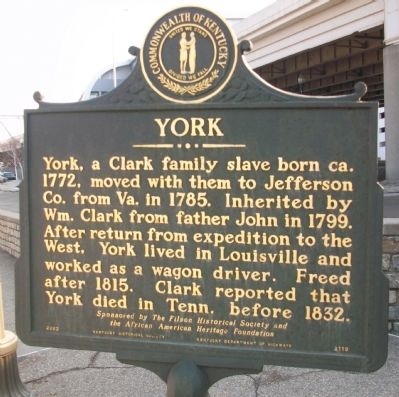

York’s story begins as an enslaved African in Caroline County, Virginia in 1784. His slave owner was named John Clark. John Clark’s son William Clark and York grew up and played together as children, but as adults, both of their lives would drastically change. York never had the legal right to a last name, so many called him York. As a teenager, John Clark gave York to his son William and made him a personal servant to William. When William Clark’s father died in 1799, the twenty-seven-year-old York legally became William Clark’s property along with the family plantation of Mulberry Hill, livestock, equipment, thousands of acres of land in Kentucky and eight slaves. Those slaves included not only York but his mother Rose, father Old York, brother Juda and sister Nancy.

From 1800-1802, William Clark and York traveled to the eastern states and Washington to visit President Jefferson. Clark became friends with the president's secretary, Meriwether Lewis, and the two served in the army together. President Jefferson wanted Lewis to prepare an expedition across the continent to the unmapped West and Lewis asked Clark to help him lead the crusade, which Clark accepted. Clark told York that he would be traveling with Lewis and Clark. York became very unhappy because he had recently fallen in love and married a young slave whom he would soon have to leave behind. As a slave York didn’t have a choice in where he went or what he was required to do. Family separation was a normal yet equally traumatic part of a slaves existence.

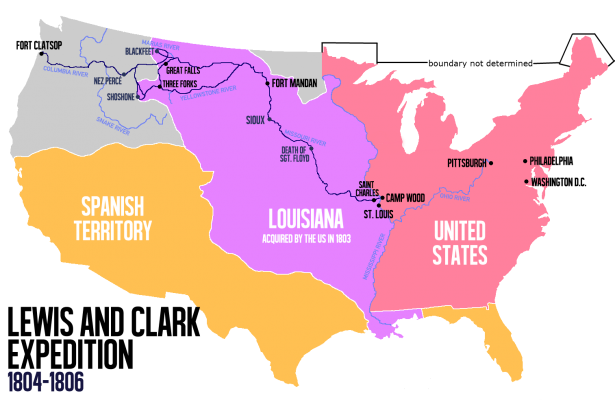

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as The Corps of Discovery, began on May 14, 1804, going by boat up the Missouri River. Both Clark and Lewis wrote detailed journal entries chronicling the journey and encounters with foreign places, animals and dangerous situations. They also wrote about York and his contributions. During the journey York lived and worked as a free person. He helped gather wild plants and vegetables, worked from sun up until sun down to ensure the safety of Clark and the other explorers and he provided valuable input on major decisions affecting the health and welfare of the expedition. In late October, the explorers decided to stop for the winter and build a small fort near the villages of two Native American tribes, the Mandan and the Hidatsa. The tribesmen had never seen anyone like York. They believed that the brown on his skin would wash away. York was named “big medicine,” and the people of the tribe admired him.

In early April, the explorers continued their journey westward. The Corps of Discovery had two new explorers: a teenaged girl named Sacagawea and her two-month-old baby boy. Sacagawea spoke the Shoshone language and Lewis and Clark hoped she would help them trade with the Native American tribe for horses to get them through the Rocky Mountains. Grueling months of travel finally led the men through the treacherous mountains and on November 7, 1805, the men discovered a bay that was twenty miles from the Pacific Ocean. They had finally arrived.

On September 23, 1806, the explorers made it to St. Louis where everyone celebrated their arrival and achievements. The explorers were all given high praise, deemed national heroes and awarded double pay and many acres of land. Unfortunately, because York was still a slave, he did not receive anything and resumed his personal servant duties for William Clark, who took a job in St. Louis working for the government. York longed to go back home to be with his wife, but he was not allowed to do so until later. York eventually spent several months with his wife, but had to return to St. Louis with Clark. Clark eventually sent York back to the family estate in Kentucky to drive freight wagons. Sadly, by then York’s wife was forced to relocate with her owner to Mississippi, and it is likely he never saw her again. Ten years after the expedition, William Clark gave York his freedom. He also gave him a wagon and six horses to start his own freight-hauling business. York’s business was not successful because White farmers rarely hired freed slaves.

Historians have stated that York died before 1832 of the disease cholera, possibly while trying to rejoin William Clark in St. Louis. Much of his life after the expedition is unknown; however, the journals of the Lewis and Clark expedition reveal pieces of who he was and what he had to endure. York risked his life many times, suffered numerous injuries from extreme heat and cold and, because of his great efforts, helped to complete one of the United States greatest expeditions. York was a former slave and an American Hero who was promoted in 2001 to the rank of honorary sergeant, Regular Army, by President William Jefferson Clinton.

More Resources:

Discovering Lewis and Clark - York

American Slave, American Hero: York of the Lewis and Clark Expedition by Laurence Pringle

The Journey of York: The Unsung Hero of the Lewis And Clark Expedition by Hasan Davis

When Winter Come: The Ascension of York by Frank Walker

York's Adventures with Lewis and Clark: An African-American's Part in the Great Expedition by Rhoda Blumberg

York, portrayed by author and historical reenactor Hasan Davis

Comments

Very interesting. Nice to

Very interesting. Nice to know more about U.S. history and those less famous in the times of it all.

Hi Nancy,

Hi Nancy,

Thank you so much for leaving your comment!

Inside tells me, that York

Inside tells me, that York was actually graduated to New York. At least that's what I'm going to call him. And there he is free. I am grateful for him, and he's the Superior in my eyes. At least, he is with his loved one now and his prayer to God was answered.

Thank you so much for this…

Thank you so much for this valuable article. I wasn’t aware of York until now and I’m well-grown.

I did not know this piece of

I did not know this piece of history. Thanks so much for this - more please!

Hi Anna,

Hi Anna,

I am so glad tha you enjoyed the blog post. Thank you so much for your comment!

hi,gabby hi Anna I want to…

hi,gabby hi Anna I want to wonder what happend in 2019 pls bc I am a intrist person

Great post! He was such a

Great post! He was such a fascinating American. I strongly recommend the historical fiction book "I Should Be Extremely Happy In Your Company," which explores the Lewis & Clark Expedition from the alternating points of views of Lewis, Clark, Sacagewea, and York. All of whom seem like incredible people, very different from each other, trying to accomplish something that had never been done before. Thanks again for bringing us this great reporting on York.

Hi Joel,

Hi Joel,

Thank you so much for reading the blog and I will definitely read that book.

Thank you for the information

Thank you for the information on York. Readers should know that African American men had a reputation of being able to get along with Native Americans. African American men often accompanied French and British fur traders and trappers in the West long before Lewis and Clark went on their expedition.

Add new comment