Captain Silas Soule of the Colorado Cavalry refused to participate in the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre, where one hundred and fifty unarmed Cheyenne and Arapaho women and children were murdered. His letters and testimony about the events of that day are the reason the truth of Sand Creek is known as a massacre rather than a glorious battle.

Silas Stillman Soule was born July 26, 1838 in the town of Bath, Maine. The family later moved outside of Boston, Massachusetts.

Silas' parents were very progressive. They had strong abolitionist beliefs and Silas' father, Amasa Soule, belonged to many anti-slavery groups.

In 1854, the Kansas Territory was opened to settlers from the United States. Since Kansas bordered both free and slaveholding states, it was uncertain if Kansas would become a free state or slave state.

Pro-slavery and anti-slavery Americans flocked to Kansas to try and influence what the state would become. This led to fighting between those who supported slavery and those who did not. Kansas was such a violent area that it was nicknamed "Bleeding Kansas." Silas' father and older brother William moved to Lawrence, Kansas to join abolitionist groups fighting there in 1854.

Fifteen-year-old Silas became the head of his family in Boston, and worked in several factories to support his mother, sisters, and younger brother.

In 1855, the rest of the Soules moved to the town of Lawrence, Kansas. Like many of the settlers who came to Kansas because of political beliefs, the Soules made terrible pioneers. The house Silas' father and brother built did not keep out the weather or animals, so the Soules often woke up covered in snow in the winter and had to fight off rattlesnakes in the summer.

However, the Soule house became an important stop on the Underground Railroad, an illegal secret organization that helped enslaved people escape into Canada.

Silas found he had a taste for the exciting life Kansas offered. He soon became a conductor on the Underground Railroad, leading groups of enslaved people between many stops into freedom. It was extremely dangerous work, as both the conductor and those who had been enslaved were always at risk of death.

He also fought with the abolitionist militia in Kansas called the Jayhawkers. They were named after a mythical Irish bird, the Jayhawk, which according to legend could not be killed.

Although Silas was only in his teens, his bravery, skill with a gun, and sense of humor made him one of the most popular fighters among the Jayhawkers. He became a member of an elite group of Jayhawkers who raided pro-slavery towns, liberating enslaved people to bring them into freedom, and helped imprisoned Underground Railroad conductors escape jail.

Though they called themselves the "Jayhawker Ten," the group was commonly known as either the "Immortal Ten" by those they fought with - or the "Terrible Ten" by those they fought against.

Silas was particularly skilled at helping people escape jail. In late 1859, he was contacted to help with a high-profile prison break. John Brown, a famous abolitionist and family friend of the Soules, had tried to organize a revolt of armed enslaved people in Harper's Ferry, Virgnia. The revolt failed and Brown was sentenced to death.

Silas was supposed to get himself arrested, and from there try to sneak Brown out of prison. Silas never got the chance to do so - when Brown learned a rescue attempt was being planned, he sent a message that he would rather become a martyr for his cause. John Brown was executed on December 2, 1859.

Silas was then asked to help free two of John Brown's followers who had also been imprisoned. Silas pretended to be drunk, yelling and tripping in the streets, until he was thrown into jail overnight for public drunkenness. From there, he was able to make his way to where the two men were held. They rejected his offer of rescue, saying they would follow in John Brown's footsteps and be executed as well.

Silas was disillusioned after his failed rescue attempts in Virginia. He did not think it was right that Brown and his men would rather die than continue to fight. While in Virginia, he received word from his family that the "Terrible Ten" were being hunted in Kansas. They warned him not to return right away. Silas decided to take time off from his life as a Jayhawker and moved to Boston, where he had lived as a child.

He spent a year in Boston, working as a printer in a publishing company. There he became friends with the poet Walt Whitman.

In mid-1860, Silas learned that his father had gotten ill and passed away. Silas' brother William, who was also tired of years of fighting, moved to Colorado after their father's death.

William told Silas he had successfully mined quartz outside of Denver, and invited his brother to join him in Colorado. Silas agreed.

Silas was not a successful miner in Colorado. However, he was soon occupied with other matters.

The Civil War broke out across the United States in April of 1861. Although Colorado was not yet a state, most Coloradans sympathized with the Union. Colorado created a pro-Union volunteer army, called the Colorado First Regiment. Silas was among the first to enlist.

Although he was only twenty-two, Silas had more military experience than most of the regiment, and quickly became a First Lieutenant.

He went on to fight in the Battle of Glorietta Pass, in which the First Regiment successfully blocked the Confederate army from moving into the West. The Regiment was promoted to an official United States cavalry unit after the battle.

The men and their leader, Colonel John Chivington, were considered war heroes. Silas in particular stood out for his bravery. Used to fighting in the bloody Kansas wars since he was a teenager, his superiors noticed that Silas was as calm during the Battle of Glorietta Pass "as if he were at a parade."

Chivington promoted Silas to Captain, and placed him in charge of Fort Lyon with Major Edward Wynkoop, one of the founders of Denver.

Silas and "Ned" Wynkoop became extremely close friends. They both wanted to make sure the Native American tribes of Colorado were treated fairly.

This was not a popular idea. Many Coloradans - including Colonel Chivington and territorial Governor John Evans - believed that Native tribes would kill all settlers unless they were killed first.

Captain Silas Soule and Major Edward Wynkoop helped negotiate two important treaties with Colorado's native Cheyenne and Arapaho populations.

The first was the Smoky Hill Council, where the United States promised peace to the Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle in exchange for the return of four white children who had been kidnapped. The second was the Camp Weld Council in late September 1864.

The Cheyenne and Arapho left the Camp Weld Council believing they had made peace and were under the protection of the United States government. Silas Soule and Edward Wynkoop thought peace had been made as well.

However, it is commonly believed that Colonel Chivington and Governor Evans, who were present at the council, were already planning an attack on the two tribes.

On November 28, 1864, Colonel Chivington gathered his troops, telling them they were facing a hostile attack. Ned Wynkoop was at Fort Riley to handle the release of Native American prisoners, so Silas spoke for the soldiers of Fort Lyon in his place.

Silas soon realized that Chivington did not have any information about an attack. Instead, he was planning to raid the peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho village in Sand Creek, where the wives, children, and elderly of the tribes were living while warriors were at the Camp Weld Council.

Silas violently opposed Chivington's plan to raid the village. No one was armed at Sand Creek, he argued, and Chivington was a coward and a murderer if he went through with his attack. Colonel Chivington threatened to hang Silas and take control of his men, but Silas continued to argue against any attack in Sand Creek.

Despite Silas' protests, on November 29th, the members of the Colorado Cavalry gathered at Sand Creek. The Union Flag was flying in the village, to signify that they were friendly to the Union and under United States protection.

Colonel Chivington gave the order to attack, but Silas warned his regiment that he would personally shoot any of his men who followed the order. Instead, the members of Silas' regiment set themselves up as a barrier between the Colorado Cavalry and the peaceful village.

Although Silas was able to save a few people - including Charlie Bent, the half-Cheyenne son of famous frontiersman William Bent - around one hundred and fifty people were murdered that day. The majority of the villagers were unarmed women, children, and the elderly, just as Silas had said.

After the massacre, Colonel Chivington wrote a letter to his superiors in Washington, D.C. stating that the Colorado Cavalry had bravely fought against hostile Indians and earned a great victory for the United States.

In his letter, Chivington mentioned that he would be keeping close watch on a troublesome captain named Silas Soule, who had proved himself "a greater friend to the Indians than the whites."

Silas was shocked and horrified at the violence of the Sand Creek Massacre. He was angry that Chivington had described the massacre as a battle, and that members of the Colorado Cavalry were treated like heroes afterward. He was determined to prove the truth of what happened that day.

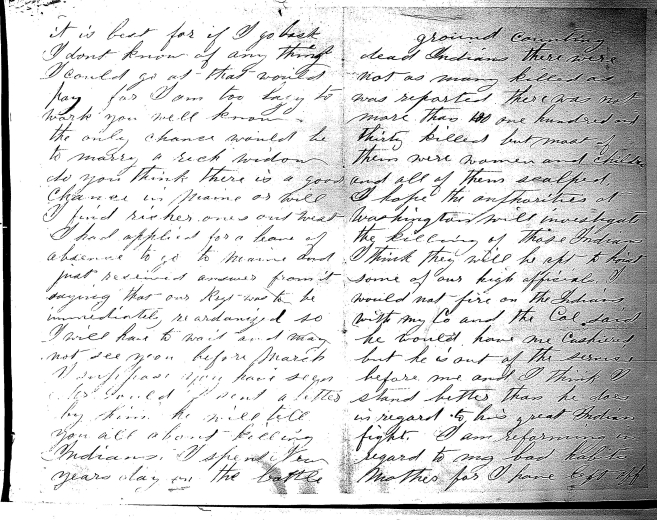

Silas wrote letters to Ned Wynkoop, explaining the graphic violence of the massacre. "I tell you Ned, it was hard to see little children on their knees have their brains beat out by men professing to be civilized," he wrote. Silas wrote letters to congressmen in Washington, D.C. and to his friend Walt Whitman, telling the truth of what happened November 29th - and that it was not at all the glorious battle Chivington described.

In January of 1865 the United States government launched an investigation into the Sand Creek Massacre. Silas was the key witness who testified against Chivington and the Colorado Cavalry, explaining the extreme violence and bloodshed against unarmed Native Americans.

By January, Chivington had retired from the army, so he could not be tried in a military court. He was not convicted of criminal charges because of the key role he played in the Civil War.

However, Chivington ended his career in disgrace. He wanted to become a governor or politician, but his political hopes were ruined once he became known as "The Butcher of Sand Creek." Chivington never forgave Silas for what he considered a betrayal.

After the end of the investigation, Silas hoped his life would return to normal. He left the army and accepted a job overseeing military police in Denver.

He and Ned Wynkoop liked to visit Coberly's Halfway House, a famous saloon between Colorado Springs and Denver. The saloon was run by Sarah Coberly and her three daughters. The middle daughter, Hersa, was known for her quick wit and intelligence. She and Silas were often seen laughing and dancing together.

In April of 1865, twenty-six-year-old Silas married nineteen-year-old Hersa. Because they both liked practical jokes, they married on April Fool's Day so none of their friends would know for sure if they had really gotten married.

On April 23rd, just weeks after their marriage, Silas and Hersa were on their way home from visiting friends when they heard shots fired in an alley nearby. Silas went to investigate.

He walked right into a trap. Waiting in the dark alley were two assassins who shot Silas, killing him instantly. A neighbor of the Soules found Silas minutes later and alerted the police, but his murderers had already disappeared.

Ned Wynkoop and Silas' brother William took Hersa to live with Silas' mother and sisters in Kansas after the murder, as they worried her life was in danger as well.

The assassins were tracked down and arrested, but they escaped prison before their trial. The two men had served in Chivington's army. Many suspected Chivington hired them to murder Silas, but it was never proven.

Silas Soule is the reason that the truth of the Sand Creek Massacre is known today. He is remembered for his strong morals and bravery. The Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes visit the grave of Silas Soule every year during the annual Healing Run to honor victims of the Sand Creek Massacre.

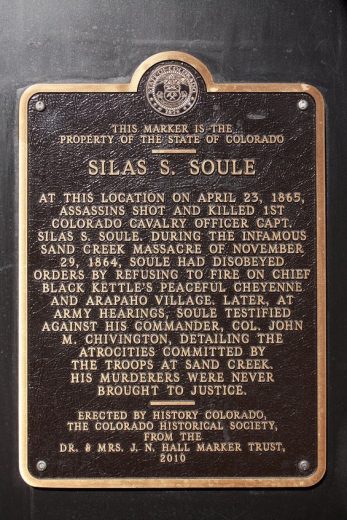

In 2010, the Colorado Historical Society unveiled a historical marker at the spot in downtown Denver where Silas Soule was murdered. Although he only lived to twenty-six, Silas Soule is remembered as one of the most important people in Colorado's history.

progressive – people who support social reforms and liberal ideas

abolitionist – someone against slavery

Underground Railroad – a secret network of people who helped slaves escape and transported them to either free Northern states or Canada. The Underground Railroad was made of abolitionist white Americans, black and white Canadians, former slaves, and free black Americans.

militia – an unofficial military force made of everyday citizens, either support an army or to rebel against it

elite – a select few considered better than the rest of the group because of skills and abilities

revolt – a violent uprising of people against the established order

martyr – a person who dies for a cause or belief in order to strengthen that belief among others

disillusioned – to be disappointed in something or someone that does not live up to expectations

cavalry – soldiers who fight on horseback

negotiate – two opposing sides come together through talking

signify – an indication of something

testify – to give evidence in a court

assassin – a murderer hired to kill a political opponent

Have you ever had to stand up for what was right, even though it was hard to do?

- What happened afterward?

How was Silas Soule's life different from teenagers you know today?

Where would you look to find out more information about the Sand Creek Massacre?

Silas Soule Manuscript Collection (Primary sources about Silas Soule, including letters and military records. Because the collection is so fragile, a copy of the collection on microfilm is available to view in-person on the fifth floor of the Denver Central Library).

Silas Soule in the Denver Public Library Digital Collections

Books about Silas Soule at the Denver Public Library:

- Silas Soule: A Short, Eventful Life of Moral Courage (The only full biography of Silas Soule. This book can be read in person on the 5th floor of the Denver Central Library.)

- Forgotten Heroes and Villains of Sand Creek (Profiles some of the key players on both sides of the Sand Creek Massacre. Short biographies of Silas Soule, Ned Wynkoop, John Chivington, Black Kettle, and others. This book may be viewed in person on the 5th floor of the Denver Central Library.)

- Ned Wynkoop and the Lonely Road from Sand Creek (Though the biography is about Ned Wynkoop, Silas Soule and the Sand Creek Massacre play a central role in the story. This book is available for check out or may be viewed in person on the 5th floor of the Denver Central Library.)

- Pilgrimage to the Site of the Sand Creek Massacre (A short booklet of photographs of the Sand Creek Massacre site and the story of the events of that day. This book can be viewed in person on the 5th floor of the Denver Central Library.)

Biography of Silas Soule from the Colorado Virtual Library

Biography of Silas Soule from the Sand Creek Massacre website

Biography of Silas Soule from the Soule/Sole Family Society

The Life of Silas Soule from the National Parks Service (Warning: includes a letter written by Silas with a GRAPHIC description of mutilations and murder at the Sand Creek Massacre.)

Testimony of Silas Soule at the Sand Creek Massacre Investigation from the Kansas Historical Society