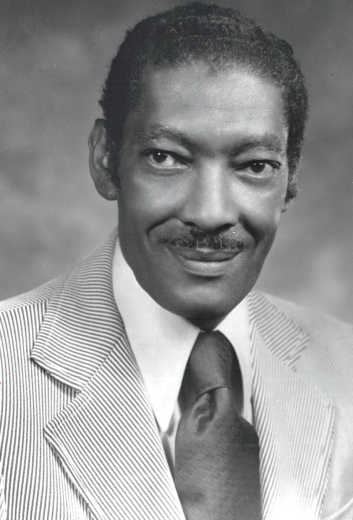

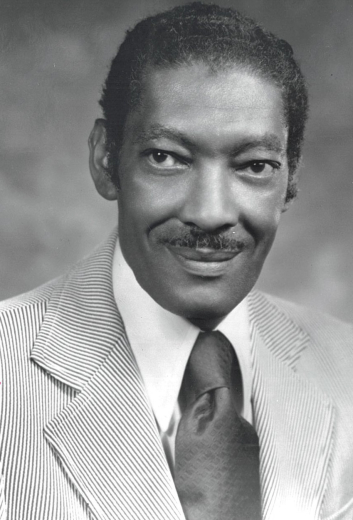

Omar Blair served in the segregated U.S. military during World War II and returned to Denver where he joined the school board and worked to integrate Denver Public Schools.

Omar Drufus Blair was born to Omar O. Blair and Lillian Ballard Blair in Houston, Texas on July 16, 1918. Omar spent his early childhood in Denver living with his mother and stepfather. Like many families during the 1920s and the Great Depression, Omar’s family struggled with poverty and tried many different means of getting by. One way they made money was by producing and selling alcohol to speakeasies, during the period known as Prohibition. Omar would sometimes deliver the alcohol to Denver speakeasies hidden in his pants, and would also catch crawfish from City Park Lake and sell them to local restaurants. Making a living during this period was particularly difficult for African Americans in Denver, because both the city and state governments were controlled by the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan fought for white supremacy and against the interests of racial, ethnic, and religious minorities.

For high school, Omar and his family moved to Albuquerque where, although the schools were integrated, he still experienced racist policies like having to sit in the back of the auditorium. Omar worked hard and achieved straight As in his classwork and, decades later, would be declared his high school’s most distinguished graduate.

Because of his excellent grades, Omar won scholarships to the University of California, Los Angeles. In 1941, after two years of school, he was recruited by the United States Army Air Force. For most of U.S. history, the military had been segregated and most African Americans were given lower status positions. Omar, however, had been recruited for a new elite group of African American pilots and support crews that would become known as the Tuskegee Airmen. Omar worked as an armorer who made sure pilots had things like fuel and ammunition. He was an original member of the 332nd Fighter Group in Europe, known as the famous “Red Tails.”

During the course of the war, Omar rose to the rank of captain and served as a supply officer. His favorite story involved him and other U.S. soldiers stopping an American supply train in Italy and taking large aircraft fuel tanks without permission. Omar’s fighter squadron needed the larger tanks in order to escort a large group of bombers that were on their way to attack Berlin and help end World War II.

As the war came to an end, many of the brave African American veterans returned to towns in America where they were still forced to drink from separate water fountains and sit in the back of buses. Years later, it even came to light that the government had performed medical experiments on some of these Tuskegee Airmen, which cut their lives short.

While Denver did not have laws that forced African American and white students to attend separate schools, communities were so separated from one another that schools ended up segregated even without such laws. In 1973, the Supreme Court of the United States upheld a lower court’s order to Denver schools to end segregation, and a program of busing began. School buses were provided to take children from distant communities around the city and bring them to different schools in neighborhoods with different ethnic and racial make-ups from their own. The program was intended to create more diversity among students from different racial, ethnic, and economic groups across the entire city.

Like with many cities and states nationwide that ended segregation with busing, changes in Denver were met with violence by those who opposed diversity within the schools. A man named Wilfred Keyes brought a lawsuit to end school segregation in Denver, and had his house bombed in retaliation. When buses were purchased to fulfill the 1970 court order that created the busing program, 37 buses parked overnight in a school lot were bombed.

Omar, who had played an important role in making the busing program work, also refused to back down to racist death threats.

“We got a lot of crackpot calls. Some fools with hoods and shotguns didn't scare me.” - Omar Blair, Rocky Mountain News April 26, 2003

Despite opposition to the program, busing was successful in making sure that public money and resources were not going mostly to wealthier white neighborhoods, but that all students had improved access to education, regardless of race or wealth. To prove the program was working, Omar set up Knight Fundamental Academy in the Bonnie Brae neighborhood. He found the best teachers for the school, and brought children in from all over Denver. When people complained about busing, he would point to how well students were doing at this new school, regardless of each student’s background. Eventually, Omar would become the first Black president of the Denver School Board in 1977.

While he was passionate about education, Omar also sought to serve the community in other ways. In 1985, he worked with others to start the Greater Park Hill Sertoma Club. After losing some of his hearing in the war, he sought to aid others, particularly children, who experienced hearing loss. Among the work done by the Park Hill Sertoma club were free hearing tests provided to newborn babies and others, and hearing aids donated for those who couldn't afford them. Omar also worked to name a Denver middle school after Martin Luther King, Jr., and was active in Denver’s historic Shorter Community AME Church.

In April 2003, the CIty of Denver bestowed a great and lasting honor on Omar. A new branch of the Denver Public Library was named “Blair-Caldwell” after Omar Blair and Elvin Caldwell (Caldwell was a state representative and city councilmember). Blair-Caldwell houses a branch library, a museum, and the African American Research Library.

Further honors include Denver Mayor John Hickenlooper declaring December 20, 2003 “Omar Blair Day.” Omar died in 2004, at the age of 85, and over 1,000 people attended the celebration of his life held at the Shorter Community AME Church. The service was attended by old friends, like Rachel Noel and former Denver Mayor Wellington Webb, along with current U.S. Representative Diana Degette, and former state Senator Penfield Tate. Omar’s memory lives on in all the students whose lives his policies touched, as well as the library that serves the Denver community in his name.

“Omar Blair created opportunities for people of color. He opened the door for a lot of folks and kept it open.” - Cleo Parker Robinson

speakeasies - secret bars people would attend to drink alcohol when it was made illegal during the 1920s and 1930s.

integrated - permitting a wide array of people regardless of race, ethnicity, region, class, etc.

distinguished - standing out in a group because of one's positive traits or skills

Do you think serving in World War II helped prepare Omar to fight for desegregation when he returned home? If so, how?

Do you think growing up in poverty influenced Omar's focus on learning in school? Why?

Do you think schools are stronger when your classmates come from many different backgrounds?

Omar Blair Clipping File (Available upon request)

Spirit at the Mountaintop Documentary

Who were the Tuskegee Airmen? / by Sherri L. Smith ; illustrated by Jake Murray