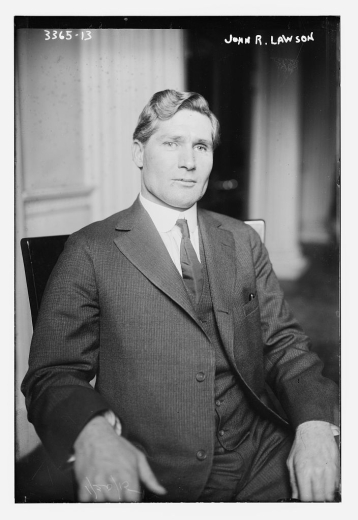

John Lawson was a union organizer during the Colorado Coal Field War.

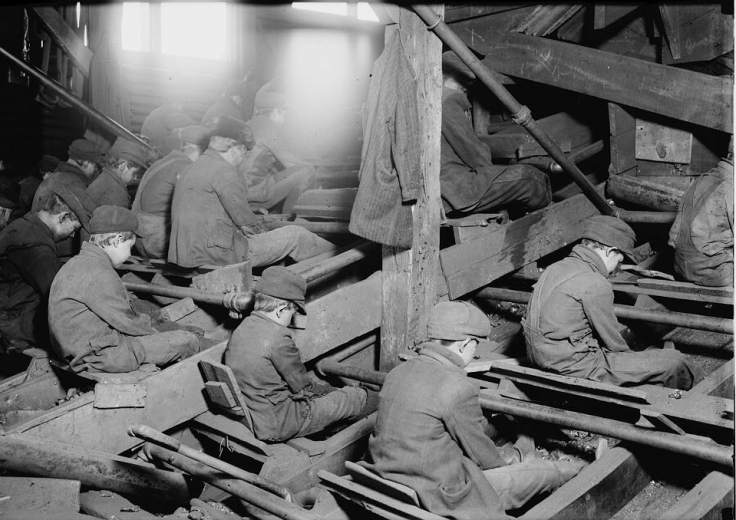

John Rankin Lawson was born in Pennsylvania on March 5, 1871. His parents, John Lawson and Margaret Rankin Lawson, were immigrants from Scotland. His father was a miner and an active union member with the Knights of Labor and later the United Mine Workers. Against his parents' wishes, John left school in the second grade to work in the mines as a "breaker boy". Breaker boys would spend ten hours per day, six days per week hunched over coal chutes to separate the valuable materials from the loose rocks. Many other boys his age were doing the same work for the 50-cent-per-day wages, but many also ended up with crooked backs, looking like old men at a young age.

John wanted to join the union immediately, but his father insisted that a man should be grown-up before becoming part of the organization. By the age of 10, John had worked his way up to the job of "trapper boy" in the Reliance Mine. Trapper boys were responsible for opening and closing ventilation shafts in order to prevent the build up of flammable gases and coal dust. Later in his life, he would try and catch up on his education through night school and correspondences courses in mining and mathematics. At 17, John was sent to Philadelphia to join his eldest brother, Colin, and learn to cut and polish granite blocks. He even helped construct some famous buildings in Philadelphia such as the Reading Railroad Terminal and the Pennsylvania Railroad Station.

In 1895, John decided to strike out for the West and meet his father who had been working in Roseburg, Oregon. His father had trouble negotiating a mine lease with a couple of mine owners, so the two soon moved to Rock Springs, Wyoming, where they worked in Mine No. 9. At the end of the season, they moved again to the coal camp of Walsen, Colorado, to work in a mine operated by Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, one of the biggest coal operators in the state. Walsenburg, near Walsen, would end up being one of the most important locations of John's life, but that would come years later.

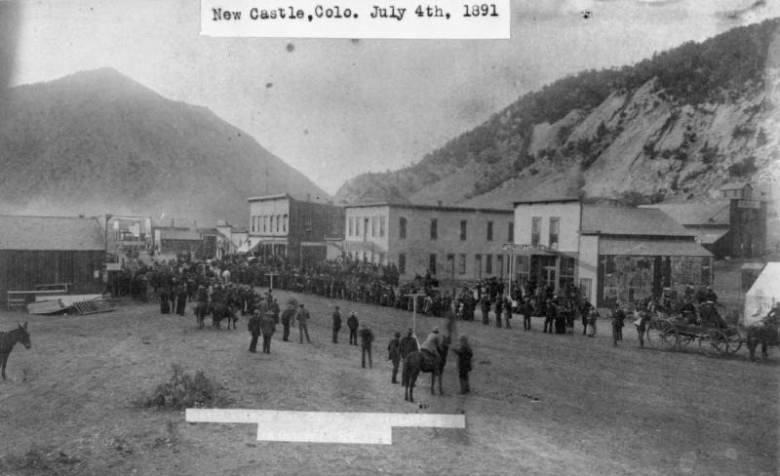

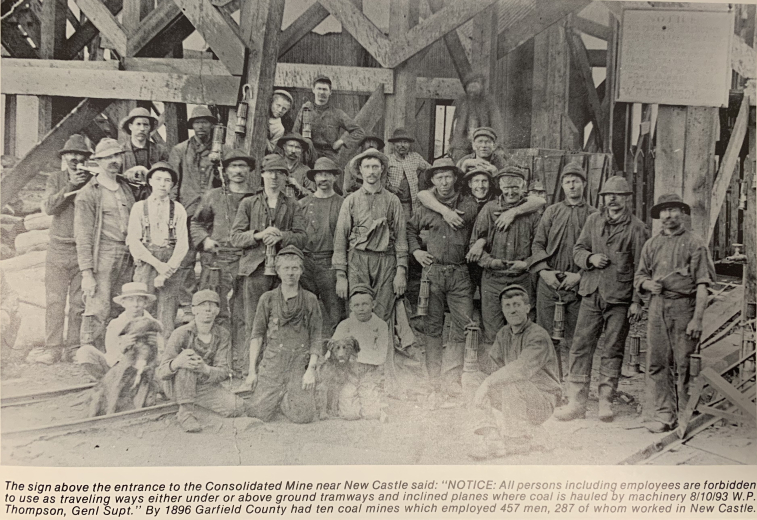

In 1896, John and his father moved to New Castle, Colorado, to work on the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company's Consolidated Mine. His father soon left for Pennsylvania, but John remained because he had fallen in love with Olive B. Hood, a local landscape architect's daughter. They were married in 1898 and went on to produce a daughter named Fern who was born during their 1900 visit to Philadelphia. By summer of that year, John returned to New Castle to begin work on the Coryell Mine, which would become central to his labor activism.

At the Coryell Mine, Perry Coryell had put in charge his own brother-in-law, Bill Rodgers, who had no experience in mining. He would even test for explosive gases using an open flame. John and his friends, who were also experienced miners, decided to get out while they could. Not long after that, an explosion killed Frank Grandi and Joe Leo and injured many others. A coroner's investigation and a jury found that Coryell had been negligent in constructing the ventilation system, in his use of open flames and in his refusal to file the required reports on mine safety.

Coryell saw no real consequences for his actions and, soon after this, the same mine experienced a massive fire that ended up closing it for good. Coryell then opened a new mine. When workers showed up, however, they were informed that he was lowering salaries below previously-established rates in that mining district. This led the United Mine Workers of America union, of which John was a member, to declare a strike on the mine and most workers moved on to the South Canon Mine down the road.

John and the other miners had established a good relationship with management of the Boston Colorado Coal Company, which owned the mine, and were able to negotiate successfully whenever any issues arose. In 1903, however, a statewide strike was organized to support the plight of other miners, particularly in Huerfano and Las Animas Counties. While the miners in South Canon were able to come to an easy agreement with management at the mine, the board of directors of the company forced management to reject any such deals.

While most of the state was on strike, miners back at the Coryell Mine had not begun striking yet. On the day the strike began, an explosion rocked the mine killing Tony Zullo. Perry Coryell immediately tried to blame the union for the explosion. The union called on the mine inspector to investigate and he found, again, that this explosion was caused by a lack of safety practices within the mine. At this point, Coryell's miners went on strike. Coryell forced them to leave their company-provided housing and most relocated to New Castle.

The strike went along peacefully until December 17th, 1903, when several strikers, including John Lawson, had dynamite exploded under their homes at 4:47 in the morning. Luckily, no one was killed, but Lawson's child, Fern, had been thrown from her crib by the explosion. At first, local law enforcement refused to come investigate. Eventually, the Lake County sheriff agreed to send a dog to sniff out the culprits, but delayed sending him. When the dog and his handler arrived, the handler would jerk them back every time they found a scent. It was clear that those in authority were covering for a potential crime committed by the mine operator.

The mayor formed an investigative committee and hired an outside detective to investigate. It began to look like the conspiracy had been between Perry Coryell, the local taxidermist who opposed the union, and the brother of the man who had been killed in the mine explosion. Dominic Zullo had blamed the union for the explosion that killed his brother. Coryell blamed the attack on the miners' homes entirely on Zullo and, though the committee didn't believe him, faced no consequences.

Not long after this, Coryell's own newspaper began publishing slanderous stories about Lawson. Lawson confronted Coryell in a barbershop and Coryell suggested they go to the street to settle things. Lawson waited in the street, thinking that Coryell meant to fight him. Instead, Coryell went to his horse and buggy, where his wife and child sat, pulled out his shotgun, aimed at Lawson's private parts and fired. Lawson was injured, but recovered. The local District Attorney refused to charge Coryell claiming that this was a common side effect of labor disputes. Eventually, Coryell would be convicted of murdering two men in Seattle and go to jail.

In 1906, Lawson was elected to the Executive Board of the United Mine Workers of America. He was now an official organizer and sought to organize areas that had been particularly hostile to unions. He went to Durango where a friend warned him,

"Get away from this field. Get away if possible before they find out who and what you are."

Within two weeks, he had organized three different local unions.

As 1913 approached, there was more success organizing the Southern Colorado coal fields. Much of this area was controlled by the Rockefellers (a powerful East Coast family) through their Colorado Fuel and Iron Company. It had been particularly hard to unionize as they would hire spies to report any men talking about unionizing. The big coal companies also brought in Baldwin-Felts and the Pinkerton Detective Agency. These were, basically, groups of hired gunmen meant to protect the mines and intimidate mine workers. During a large gathering of state labor leaders on August 17, 1913, two Baldwin-Felts gunmen approached Gerald Lippiott, a United Mine Workers organizer, and shot him dead in the middle of the street.

Despite the constant violence and intimidation, the convention passed a series of demands including an eight hour work day and the enforcement of mine inspection laws. John Lawson, Ed Doyle, Frank Hayes and John McClennan, who made up the policy committee, then called for a district convention of miners in Trinidad. Three hundred miner representatives attended and a resolution was passed to strike because of the absolute refusal of the companies to even entertain their demands. Lawson tried meeting with management of the coal companies, but they refused to even consider a settlement.

As with previous strikes, the miners and their families were forced to leave their company housing and set up a tent city. Lawson went to meet with Colorado Governor Elias Ammons who informed him that the coal companies were pressuring him to declare martial law and force the miners back to work. Lawson said he would take charge of the camp city himself and make sure that peace was maintained in the camp in order to avoid providing an excuse for extreme action by the state.

He assured the governor that not only would there be peace within, but that he would assure the people that their homes would not be threatened by the coal companies' hired gunmen. He organized groups to look after sanitation, welfare, distribution of supplies and a very effective police force. The police force included many men who had immigrated from Europe and several had military experience from various European conflicts.

The company gunmen, who had been provided with machine guns by John D. Rockefeller Jr., did not cease their intimidation and there were several clashes between them and miners outside the camp. They even built an armored vehicle named "Death Special" with machine guns on it that they would drive around shooting at people. They even mistook a man working on a ranch (Mack Powell) for a striker and shot him in cold blood. They also started firing machine guns into the camp at night. Random people were killed and others dug cellars under the tents to sleep in to avoid being shot at night.

By October 1913, the state militia had been sent by the governor and soon joined up with the companies' militia. The local Sheriff, a pro-company man, also deputized the Baldwin-Felts gunmen. Things continued to heat up and Rockefeller, even after being asked by Congress to find a way to peace, refused to bring an end to the violence. On April 20, 1914 everything boiled over.

Several National Guardsmen came to talk to Louis Tikas about reports that a man was being held against his will. Louis, a Greek miner and union organizer agreed to talk to them. At that moment, Karl Linderfelt, a Colorado Guardsman with a very violent past set off three explosions nearby. He claimed that they were to call for reinforcements. Whatever the motivation, the explosions set off shooting between the strikers and the National Guard and the companies' militia.

Some of the women and children ran to a dry creek bed for cover. Others hid in the cellars beneath the tents. The shooting lasted all day and machine gun fire poured into the tent city. Later, Linderfelt and his men stormed into the camp and set fire to the tents. Four women and 11 children suffocated to death while the fire raged above them. Shortly after, Karl Linderfelt ordered Louis Tikas and other strikers brought before him. Linderfelt then cracked Tikas' skull with his rifle stock. The bodies of Tikas and his friends were found three days later.

US President Woodrow Wilson tried to appeal to Rockefeller and other mine owners, but they refused to seek peace. Eventually, Wilson had to send in federal troops in order to end the bloodshed. By December, the union was out of money and the strike ended. The company tried to get Lawson and others convicted of the murders of mine guards. Eventually, using a hand-picked jury and other corrupt practices, Lawson was convicted, but the conviction was overturned by the Colorado Supreme Court in 1917.

John R. Lawson kept busy for the rest of his life. He remained on the executive board of the United Mine Workers of America for a decade. He served as a coal mine inspector and, eventually went on to serve as vice president of Rocky Mountain Fuel Company from 1928 to 1939. He also served as the dean of the labor college at Grace Community Church in the 1930s. He died in his home at 1720 Sherman Street in 1945 at the age of 74 and is buried in Fairmount Cemetery.

John grew accustomed to hard work starting in the second grade and never stopped working. His focus gradually shifted from merely working to feed himself to working to make sure his fellow workers got a fair deal. He tried to achieve that goal through peaceful means, but often found himself and other miners met with violent resistance. It is due to the persistence of John and men and women like him that most workers today are guaranteed a 40 hour work week, safer working conditions and a ban on child labor. The struggle did not begin or end with John Rankin Lawson, but he played a vital role in making America a better place for millions of people.

union - workers that organize to negotiate as a group with an employer

ventilation - working to make sure fresh air flows through an area

correspondence courses - learning done with educational materials sent by mail

negligent - failure to take proper care of someone or something

plight - a struggle

culprit - someone responsible for doing something wrong

martial law - controlling an area through military force

What do you think motivated John Lawson to become a union organizer?

Why do you think mine owners were able to get away with so much?

Are there any conflicts today that remind you of these conflicts a century ago?

![Hundreds of coal miners march in a funeral procession for Ludlow Massacre victim Louis Tikas, on North Commercial Street in Trinidad, Las Animas County, Colorado during the UMW labor strike against CF&I. Business signs read: "Laundry", "Trinidad Hotel", "[New Met]ropolitan Hotel", "Wrigley's Spearment", "Colorado [S]upply Co.", and "The Pierc[e.]"](/sites/history/files/styles/story/public/cdm_35199.jpg?itok=-e1wEyOc)