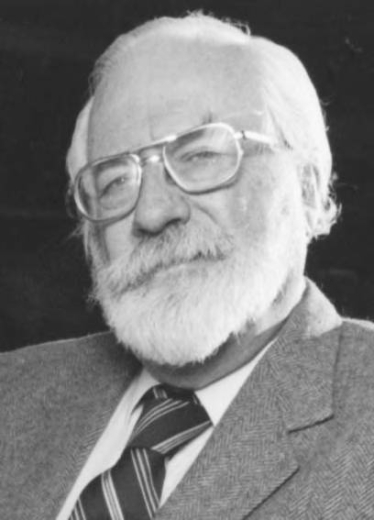

The "Father of Denver Theater," Henry Lowenstein survived the Holocaust to become one of Denver's most famous stage producers.

Heinrich Lowenstein was born July 4, 1925 in Berlin, Germany. His father was a doctor and his mother was an artist. Heinrich grew up immersed in the busy Berlin art and theater community.

Heinrich loved to draw, and spent much of his childhood sketching and painting. The Lowensteins' happy home life came to an end in the late 1930s, when Adolph Hitler took power in Germany.

Hitler thought that Jewish people were the cause of all trouble in Europe. He wanted to get rid of Jewish people living in Germany.

Heinrich's father was Jewish, but his mother was not. Heinrich had an older half-sister named Karina, who was not Jewish either. The Lowensteins still were very afraid, because many of their friends and neighbors were killed in the Holocaust.

In 1939, the Lowenstein family was ordered to report to a concentration camp.

Thirteen-year-old Heinrich was saved and taken to England on the famous Kindertransport. Karina managed to escape the concentration camps because she was not Jewish. She sent important information to the United States to help them defeat Germany.

Heinrich's parents were lucky that they were not sentenced to death - because Maria Lowenstein was not Jewish, she was able to protect her husband. However, they were held prisoner in forced labor camps until the end of World War II.

In England, Heinrich became fluent in English and took drawing classes. He changed his name to the English version of Heinrich, Henry.

He lived in London until 1940, when the city was bombed for fifty-seven days straight by Germany.

Like many Londoners, Henry fled into the countryside, and worked on farms until the end of the War in 1945.

In 1946, the United States government arranged for the Lowenstein family to move to Pennsylvania to thank Karina for the information she had sent during the War. Henry moved from England to the United States, and was reunited with his family for the first time in seven years.

Henry attended high school for the first time in Pennsylvania. Even though he was much older than the other students, he loved his advanced art classes.

In 1950, Henry joined the United States Army. He illustrated training manuals for soldiers fighting in the Korean War. Henry served in the Army while he worked on becoming a United States citizen.

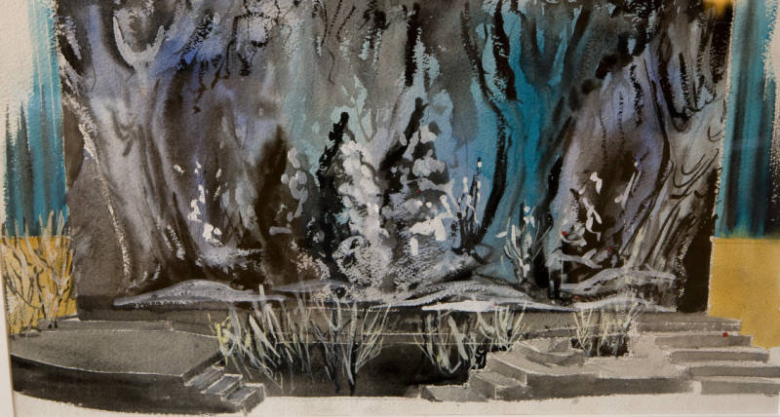

Henry earned his citizenship in 1953. That same year, he applied to the Master of Fine Arts program in Theater Set Design at Yale University.

Even though Henry had never been to college, the admissions committee at Yale was so impressed by his drawings that he was admitted into the program without needing to get a college degree. Henry helped create sets for Broadway plays while he was in school.

In 1956, Henry met the Denver Post heiress Helen Bonfils. She came to Yale to find a set designer for her new theater in Denver. Helen Bonfils was very impressed with Henry's work, and offered him a job at the Bonfils Theatre. Henry agreed, and moved to Denver after his graduation.

The Bonfils Theatre opened in 1953 and was the first live theater to open in Denver in over forty years. It was considered one of the best theaters in the country, and was one of the biggest parts of Denver's social scene.

Henry worked as the set designer and producer for the Bonfils Theatre. In 1967, Henry became the general manager of the the theater as well.

Right before Henry's first show opened at the Bonfils Theatre in 1956, the building's custodian died of a heart attack. Henry knew he had to find someone to take over the building before opening night. The next day, a young man and his son walked into the theater, and the man told Henry he was looking for a job. The man's name was Jonathan Parker - he wanted to become a doctor, but he was willing to do any work available to support his family. Henry offered him the job as a custodian, and Jonathan accepted.

Many people at the theater were upset with Henry for offering a job to Jonathan. Denver was segregated in the 1950s, and Jonathan was African-American. Some white actors did not want to work in a building with a black custodian.

This made Henry very angry. He did not want black Americans to be treated the way his Jewish family was treated in Germany. He called Helen Bonfils and told her what happened. Helen Bonfils wanted her theater to be open to everyone. "Of course you will hire him," she told Henry.

Jonathan Parker did not become a doctor. Instead, he became one of Denver's most successful stage actors. Henry cast Jonathan in many roles. Jonathan's daughter, Cleo Parker Robinson, became an internationally known dancer and choreographer.

Henry and Helen Bonfils worked hard to make sure that the Bonfils Theatre was a place without discrimination. Henry hired talented people who could not get jobs at other theaters because of their race. He helped many women become directors at a time when directing was considered a job for men only.

Henry designed and produced over 400 plays between 1956 and 1986.

Henry knew it was important for people to be involved in theater. He helped bring theater programs to Denver schools, and hosted the Creative Drama program for Colorado students at the Bonfils Theatre.

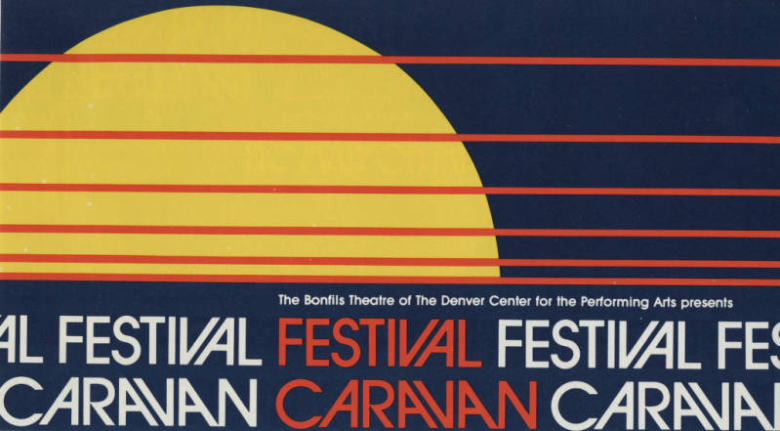

Henry also wanted to make sure that people who were not able to go to the theater had a chance to enjoy plays. In 1967, Henry brought summer musicals to Cheesman Park. In 1972, he created the Festival Caravan Theatre. These were mobile stages that toured throughout Colorado bringing musicals and plays to the public.

In 1985, the Bonfils Theatre was renamed the Lowenstein Theatre after Henry. Henry retired in 1986, after opening the Denver Civic Theatre downtown.

Henry remained active in the theater community, and helped create the Scientific Cultral Facilities District in Denver. He decided he loved working directly in the theater too much to stay away, and came out of retirement only a few months later.

Henry produced more than 90 additional shows before retiring for good in 1995.

Henry continued to encourage aspiring actors and directors of all backgrounds, and loved to help with school theater programs.

Henry also thought it was important to work with Holocaust groups. He did not want people to forget what had happened in Germany. Henry helped connect people who had moved to America after the Kindertransport, and he was active with many Holocaust survivor groups and museums.

Henry changed the face of Denver theater to include women, children, and people of all races. He brought plays to schools, parks, and communities that would not have been exposed to drama otherwise.

The Colorado Theater Guild named their annual awards "The Henrys" in his honor.

When Henry Lowenstein passed away in October of 2014, he left behind a thriving theater community. Henry opened the doors of the theater to whoever was interested, and dedicated his life to promoting diversity in Colorado theater.

immersed – deeply involved in an activity or group

Holocaust – the killing of around 6 million Jewish people by the Nazis between 1933 and 1945

concentration camp – a small, often dirty area to house a large number of political prisoners or persecuted people

Kindertransport – German for ‘Children’s Transport’. An effort by England to help Jewish children escape the Holocaust in Germany. Some children, like Henry, lived in group homes, while others were fostered by English families. Parents were not allowed to travel with their children. Most children were orphaned after the War – over 90% of the families of Kindertransport children were murdered during the Holocaust.

set designer – the person in charge of props, scenery, and often costumes for a play

custodian – a person whose job is to take care of a building, including cleaning and maintenance

segregated – the forced separation of different races in a community, including different facilities for white and non-white people

choreographer – a person who creates dance sequences and shows for a dance group

discrimination – unjust or unfair treatment of people based on race

thriving – successful or popular

Why was it so important to Henry that everyone be included in the theater?

The Kindertransport took children ages 14 months to 16 years who were trying to escape the Holocaust. They could not travel with parents.

- Who in your family would qualify for the Kindertransport? You? Siblings? Friends?

- Imagine you had to go to a new country with only those people. How would you feel? What would life be like?

Do you have a favorite play, movie, or tv show? What do you like about it?

Do you think it is still important for people to be involved in drama programs? Why or why not?

Henry Lowenstein Manuscript Collection (Primary sources including letters, drawings, scrapbooks, posters, and photographs about Henry Lowenstein and his work. The Henry Lowenstein collection can be seen in person on the 5th floor of the DPL Central Branch.)

Henry Lowenstein Oral History (In the 1981 interview, Henry discusses the Holocaust, the Bonfils Theatre, and members of the Denver theater community. The oral history is on audio cassette. Please visit the 5th floor of the DPL Central Branch to listen to the casettes in person.)

The Magic of Henry: Tribute to Henry Lowenstein (This 1990 video cassette can be viewed in person in the audio-visual room on the 5th floor of the DPL Central Branch.)

Henry Lowenstein in the Denver Public Library Digital Collection

Biography Clipping Files (Newspaper articles, journal articles, and obituaries of Henry Lowenstein that can be seen in person on the 5th floor of the DPL Central Branch.)

Biography of Henry Lowenstein from the Southwest Orlando Jewish Congregation

The Lowenstein Family: A Story of Survival Denver University Online Exhibit

The Lowenstein Family Papers at Denver University

Obituary of Henry Lowenstein by Colorado Public Radio (includes audio)

Obituary of Henry Lowenstein by the Denver Center for the Performing Arts

Obituary of Henry Lowenstein by the Denver Post

Video Tribute to Henry Lowenstein by the Denver Center for the Performing Arts