Hattie McDaniel was the child of former slaves who grew up to be the first African American to win an Academy Award.

Hattie McDaniel was born June 10, 1893, to Henry McDaniel and Susan Holbert. Henry had been born into slavery on a Virginia plantation. During the Civil War, he served as a Union soldier and, after the war, he traveled around doing odd jobs as well as performing. In 1875, he settled in Nashville, Tennessee to serve as a Baptist preacher. This is where he met Susan, who was already a popular religious singer in Nashville. Following the end of the Civil War and the freeing of enslaved people, in 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes unfortunately ended Reconstruction laws that had served to protect African Americans in the South from legal discrimination. This change in legal protection allowed for the beginning of Jim Crow laws and caused many African Americans, including Hattie’s parents, to move west in search of greater freedoms and a better life.

The couple ended up in Wichita, Kansas, where they had 13 children. More than half of their children died at birth or in early childhood. Of those who survived, Hattie was the youngest. In the early 1900s, the family moved to Fort Collins, Colorado, and then settled in Denver. During her childhood in Denver, Hattie’s love of song and dance would develop and grow. Hattie attended 24th Street Elementary school, where she enjoyed reciting poetry and singing popular songs in front of her teacher and classmates. After completing elementary school, Hattie and her best friend, Willa May, went on to East Denver High School together. She continued to excel at song, dance, and theater. Hattie even received a standing ovation and a gold medal from the Women’s Christian Temperance Union for her rendition of the poem Convict Joe, a story about the evils of alcohol abuse.

By 1910, Hattie’s father Henry and her brothers Otis and Sam had a change in careers. Henry formed his own minstrel show with Otis and Sam. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, minstrel shows had become a popular form of entertainment among white audiences. The shows focused on racist stereotypes of African Americans performed by white singers and comedians with their faces painted black for laughs. This type of performance was called “blackface.” While these shows promoted racist ideas that thrived across the country, minstrel shows were one of the few places where African American artists could highlight dance and musical styles that grew out of their communities, such as Ragtime and Jazz. Hattie’s mother forbade her from joining the family show, because her father and brothers traveled around the state, and many remote parts of Colorado were not safe places for African Americans to travel and stay.

Hattie would not be dissuaded from her desire to perform, and she left high school in her sophomore year in order to pursue her dream of making a living as an entertainer. Her departure broke her mother’s heart, as she had hoped to see her daughter graduate high school. Hattie preferred to spend the next several years perfecting her craft on the road. She would travel across Colorado and as far out as California. She sometimes performed with the Spikes Brothers Comedy group, but mostly traveled with her father’s minstrel show. In addition to practicing and perfecting her performing skills on these tours, Hattie also developed new abilities in songwriting. During this time, she also married her first husband, Howard Hickman. They lived for a short time at 32 Meade Street in Denver, until he died of pneumonia in 1915. In 1916, after a few years traveling with the family, her older brother Otis died from an unknown illness. With Otis gone, the act suffered, and the family spent less and less time on the road.

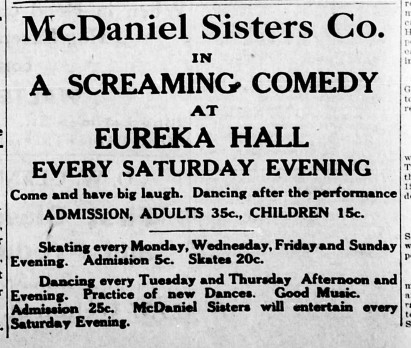

Hattie soon became more and more popular in Denver performance halls. She often performed with her sister Etta in local theaters, including the East Turner Hall, a German-American community center located at 22nd and Arapahoe in Five Points. By 1916, Etta and Hattie, now billed as “The McDaniel Sisters,” were performing their own two-act comedy with a full cast, and music performed by George Morrison’s orchestra. One 1917 review from the Denver Star newspaper said the performance brought the house down, that Hattie left people screaming with laughter, and that George’s orchestra was unforgettable. George and his orchestra would soon relocate to New York to record and launch national tours. Hattie would join them to take part in those performances.

In the early 1920s, Hattie began touring with George Morrison’s orchestra on the Pantages Vaudeville circuit. This circuit was a series of theaters across the West and Midwest where singers, dancers, comedians, and other performers would tour and perform before different audiences. Unfortunately, as moving pictures, or “movies” grew in popularity, the interest in these shows decreased. In 1926, Hattie found herself stuck in Milwaukee, Wisconsin with no money and no show, and took a job as a maid at Sam Pick’s Suburban Inn.

As Hattie later recounted, one night past midnight when Hattie was working late at the Inn, the performers who had been entertaining at Sam Pick’s that evening had all left and the manager needed more entertainment for the customers. Hattie volunteered to perform. She went immediately to the stage and started singing the song “St. Louis Blues.” The audience loved her performance, and Hattie ended up performing at the inn for the next two years. In 1931, she decided to move to California to try and work in the film industry. From this point on, her Hollywood career grew in leaps and bounds.

After arriving in California, Hattie began working as an extra, performing in the background of movie scenes. She continuously visited various movie studios in order to make herself known and began taking acting roles in films such as The Little Colonel, Showboat, and many more. Her biggest break, however, came when she was given a role in the 1939 film Gone with the Wind. Her performance in this film led her to become the first African American actor to receive an Academy Award, or Oscar, for her role as the enslaved house servant “Mammy." While her performance in the role made her famous, it was also one that embraced many early twentieth century stereotypes of an enslaved African American during the Civil War.

Despite Hollywood racism that led to fewer acting roles available for people like Hattie–and many of those roles being limited to playing enslaved people or servants– her performance in Gone with the Wind led to universal acclaim. Despite their work on the film, Hattie and other Black cast members were not allowed to attend the premiere of the film in Atlanta. While she was awarded her Oscar in Los Angeles, because the Academy Awards were also held at a “whites only” hotel, she had to receive special permission to attend the event and receive her award. She was also seated separately from the white cast members in attendance.

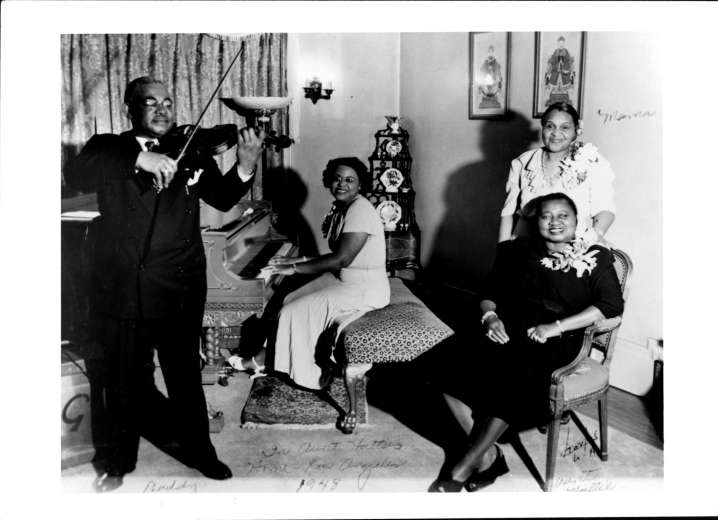

Hattie McDaniel would continue to work into the 1940s, including publishing three of her own songs: “Just One Sorrowing Heart,” “I’ve Changed My Mind,” and “Boo-Hoo Blues.” She was also part of the cast of the national radio program Showboat. In 1941, she paid her last visit to Denver and was welcomed by Colorado Governor Ralph Carr, as well as her longtime friend George Morrison. When television started to grow in popularity, she starred in her own show “Beulah.” While she was still limited to playing a servant, the show was one of the first with an African American playing the lead role. Unfortunately, Hattie had already begun her struggle with breast cancer, and she eventually died in 1952. Her last wish was to be buried in the Hollywood Forever Cemetery where many other movie stars are buried, but she was denied because the cemetery was “whites only.” In her will, she left her Academy Award to Howard University, a historically Black college, but it disappeared in 1972.

Jim Crow - a system of legal discrimination against African Americans

Temperance - the movement to ban alcohol

Stereotypes - often inaccurate views of a certain group of people held by another group of people

What do you think it was like being born to former enslaved people and still having to accept negative stereotypes of people like you in order to be a performer. Why do you think Hattie was willing to do that?

Can you think of any other groups of people who are often portrayed as certain stereotypes in movies and television? Why do you think that continues to happen?

Do you have certain abilities that you seek to develop and become the best at the way Hattie did? What are those?

Clipping Files (Available Upon Request)

Hattie : the life of Hattie McDaniel / Carlton Jackson

Hattie McDaniel : Black ambition, White Hollywood / Jill Watts