Guadalupe "Lupe" Briseño grew up without much money or education, yet went on to lead the first floral workers union in Colorado at the height of the Chicano movement.

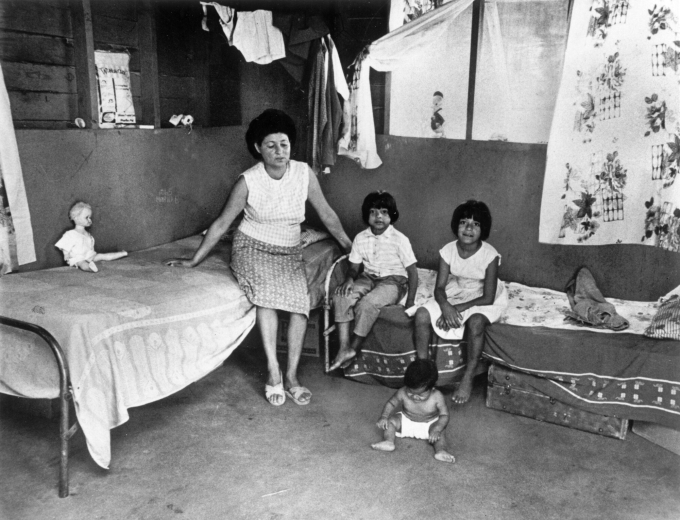

Guadalupe “Lupe” Villalobos was born in San Antonio, Texas in 1933 to Frederico and Maria Villalobos. She had seven siblings. According to her family, her future husband, Jose Hernandez Briseño fell in love with her at age 10 and proposed to her when he was 12. They married and started a family after she turned 18 in 1951. Things were not easy for Lupe, Jose, and their children. They spent a decade as migrants, moving several times a year around the Southwest while her husband performed difficult work harvesting crops. Lupe worried about their children getting a proper education with all the moves. She also faced the horror of having their three-year-old son die of pneumonia. Tired of moving repeatedly, the family resolved to settle in Brighton, Colorado in 1962. In 1968, the youngest child finally started in school and Lupe began looking for work. While she only had a high school education and little work experience outside of migrant work, she became an important leader within a much larger and important movement.

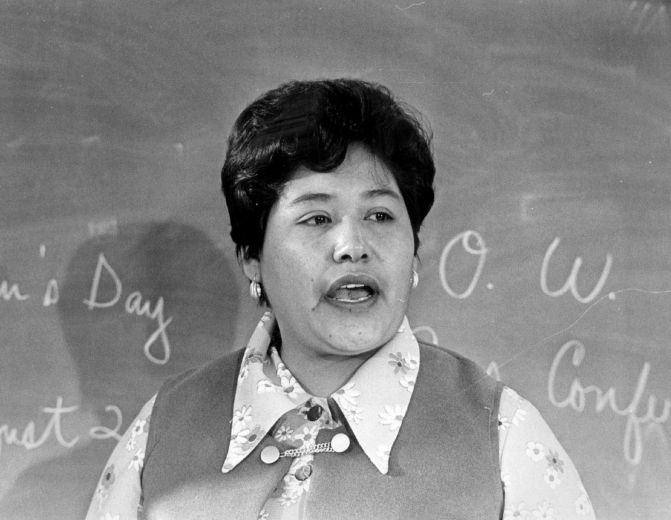

In 1968, Guadalupe “Lupe” Briseño worked for Kitayama Brothers greenhouses in Brighton. Before long, she served as president of the newly founded National Florist Workers Organization (NFWO). The NFWO sought a minimum wage of $1.60 per hour, better working conditions, and recognition of their collective bargaining rights.

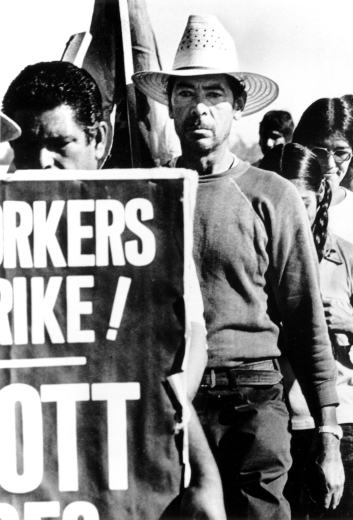

Thus, they began a strike against the Kitayama Brothers. With support from the Chicano rights group Crusade for Justice, the greenhouse workers sought the right for collective bargaining for all employees. Their strike soon received broad support that included a visit from U.S. Senator Eugene McCarthy and a donation from the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Fund, through Denver’s New Hope Baptist Church. Members of the Colorado Civil Rights Commission and Core City Ministries joined the strike through the summer of 1968. Employer Ray Kitayama accused the strikers of throwing things at floral delivery cars and told the Denver Post that the workers were quickly replaced.

A few months into the strike, Ray Kitayama was charged with misdemeanor assault for bumping Lupe in what she said was a deliberate act, though he would later be found innocent in court. Workers were also charged in Adams and Weld County courts with assault and the blocking of roads. Lupe was soon fired for organizing a union, though this is not a crime. She filed charges of unfair labor practices against Kitayama Brothers with the Colorado Industrial Commission. According to the Denver Post on 9/10/1968, Ray Kitayama stated he would never recognize the union because, “there are no unions in agriculture.” By September, the NFWO’s support on the picket line from other groups like Crusade for Justice began to severely wane. By late November, there were often only six marchers on the picket line. Later that month, however, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers would contribute $1,000.00 to the NFWO.

Solidarity also grew between groups like Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers Organizing Committee and the NFWO. The Kitayama Brothers also operated in California, and the unions sought to unify boycotts of California grapes and Colorado’s Kitayama carnations. The Church Women United organization lent their support to both groups, and pushed citizens to promote Congressional expansion of the National Labor Relations Act. Up until this point, the act did not cover farm workers. Briseño spoke at a Crusade for Justice meeting, urging support for an expansion of National Labor Relations Act coverage to protect farm workers. Lupe also spoke for expansion of the Colorado Peace Act in pursuit of labor rights for agricultural workers. In the waning days of the strike in mid February 1969, Lupe and four other women chained themselves to the greenhouse fence in a final act of defiance against a Weld County Court injunction against blocking the property. Police were brought in to spray the women with tear gas and cut the chains with welding equipment. While they still had not gotten union recognition, in the end most of their other demands were met over the year-long strike.

After the strike ended, boycotts continued and protests were organized at the Colorado State Capitol to support legislation for agricultural workers. Increasingly, more women became organized and active in the civil rights and labor movements. In 1970, Lupe Briseño received an achievement award from the National Organization of Women along with several other activists. The following year, Briseño was a prominent speaker at the Concilio de Unidad, or Unity Council, which attempted to bring together 100 Chicano organizations from across Colorado to find strength in numbers.

In 2019, the Center for Colorado Women’s History honored various leaders in the women’s rights movement, including Briseño. That same year, History Colorado hosted an exhibit on the Chicano movement featuring Briseño and other prominent Chicanas. In 2020, Briseño was inducted into the Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame for her work in the labor movement and civil rights more generally. She was given a stone and plaque along Brighton’s “Legacy Pathway” in 2024 and died that same year at the age of 91. At the time of her death, Briseño had four remaining children, eight grandchildren, and 21 great-grandchildren. She is remembered fondly by her family, and will be remembered for her contributions to a movement that still impacts life in migrant communities today.

migrants - a person who moves regularly in order to find work especially in harvesting crops

pneumonia - an inflammation of the lungs that causes breathing problems

strike - workers stopping their work in order to get an agreement from their employer

wane - to become smaller

solidarity - people standing together over an issue or cause

boycotts - to not engage with a business or buy a product because of a company's behavior

injunction - A court ordering someone to do something or to not do something

What about Lupe's life story do you think prepared her to become a leader in her union? Is there a part of your life story that might make you a good leader?

Have you ever come together with other people for a common cause? Were you able to make things better?

Clipping file (Available upon request)

Who was Cesar Chavez? / by Dana Meachen Rau ; illustrated by Ted Hammond.

Dolores Huerta / written by Monica Brown ; interior illustrations by Gillian Flint.