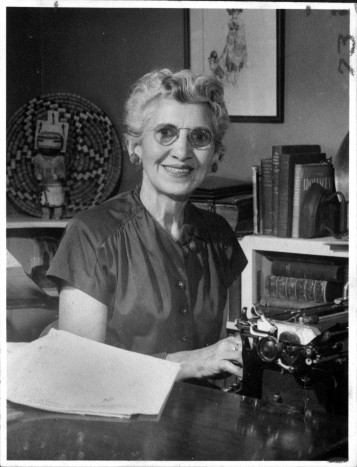

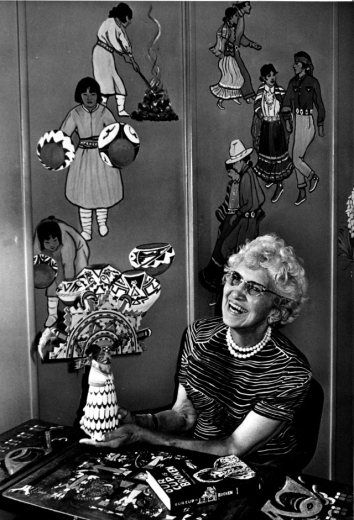

Florence Crannell Means was a children's book author who was willing to learn about and write about marginalized groups when most did not.

Florence Crannell Means was born May 15, 1891, in a house adjoining the Baptist church in Baldwinsville, New York. Her parents were Baptist minister Philip Crannell, and his wife Fannie. In her later years, Florence remembered hearing the church bells ringing regularly above her childhood home. She also remembered her father giving her a notebook and encouraging her to take notes on his sermons, and to try her hand at drawing illustrations. As the child of a minister, she also got to know people from all walks of life. She was invited to fancy dinners at the homes of the wealthy, but also became close friends with children who lived in the poorer areas of town.

In her autobiography, Florence wrote, “In a wholesome and practical way we learned that people were interesting and valuable not because of possession or position.”

This perspective would lead her to a lifetime of writing books that explored the lives of people who were marginalized and discriminated against.

When Florence was eight years old, the family moved from New York to Topeka, Kansas. She was very homesick for New York, but became fascinated by the history of westward expansion. The topic of settlement across the American West would be the basis for her first book. Florence’s father continued to encourage her writing, while her mother helped her develop her artistic skills. When she was 17, she moved with her mother and her sister to Denver in an attempt to aid her sister’s failing health. Her sister likely suffered from tuberculosis and Colorado's dry climate made many suffering with the disease feel better. Florence attended East High School at its old location downtown, and continued to write and study art. Her sister died not long after moving to Denver and her mother returned to Kansas, but Florence would stay and start her life as an adult in Denver.

In 1912, Florence married Carleton Bell Means and the following year they had a daughter named Eleanor Crannell Means. Florence co-wrote her first book with Harriet Louise Fullen in 1929. The book, titled Rafael and Consuelo, focused on the lives of Latinos in the United States. This was a rare subject, particularly for a children’s book at the time, and it set her apart as an author interested in documenting the lives of people that were largely ignored by mainstream publishing. In researching these stories, Florence and her husband spent a great deal of time visiting Latino communities in Southern Colorado and New Mexico. She believed that knowing too little about people different from ourselves led to distrust, which led to hatred and violence.

In 1936, Florence published Tangled Waters, a book about growing up on the Navajo reservation in Arizona. To prepare for the book, she spent a great deal of time on the reservation attending religious ceremonies and meeting local people. She even met Henry Chee Dodge, an important Navajo leader. He personally remembered the 1863 “Long Walk,” when Kit Carson forced thousands of Navajo from their land in Arizona to Fort Sumner in northeastern New Mexico. On that walk, hundreds of men, women, and children died along the way and, after suffering in New Mexico for years, most eventually returned to Arizona in rags. Florence’s novel tells the story of a Navajo girl named Altolie who experiences the changes her culture is going through as she interacts with people her own age, as well as people like her step-grandmother who is angry about what was done to their people.

One of Florence’s most controversial books was published in 1938. It had been inspired by two African American girls she met while visiting South Carolina. They asked her to write a book about people like themselves. At the time, the publisher was nervous about the project because they believed no one would buy such a book. The book, Shuttered Windows, was one of the few early books written by a white author with African American main characters. The main character, Harriet Freeman, is a 16-year-old girl from a well-funded Minnesota high school who goes to live with her great-grandmother in a very poor community on islands off the coast of South Carolina. Many of these islands, such as the ones Florence visited and wrote about, are home to the Gullah Geechee people. This community has their own language, called Gullah. They were also able to maintain many more African traditions than the descendents of enslaved people on the mainland were able to do. While Florence was writing about these people in the 1930s, even today many Americans are still not aware of their rich history.

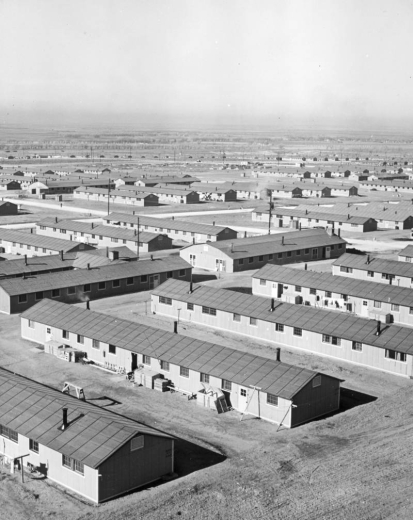

While many of Florence’s books deal with different groups of people in very different locations all around the country, one of her most important books–The Moved-Outers–took place in the state of Colorado. During World War II, thousands of Japanese American families on the west coast were sent to concentration camps around the country. This was done because some in the American government feared that Americans of Japanese ancestry would work to serve the Japanese government with whom we were then at war. One such concentration camp was called Amache, and it was located near Lamar, Colorado. Florence and her family had friends in the Japanese American community and she pushed to get permission to visit the camp. In her recordings, she talked about not being allowed to take photos or stay in the camp overnight, as the government restricted what the American public was allowed to know about these camps.

In her recordings, she also spoke about how hard Japanese Americans worked to make the camp comfortable, but also what an injustice it was that these Americans lost their homes and businesses simply based on their ethnicity. Her 1945 novel The Moved-Outers was all about these families trying to adjust to life in these concentration camps. Her book was the only novel written about the subject at the time, and it was the first time one of her books inflamed hatred against her.

“Words of hate were directed against me as a result of that book. It was the first time I’d ever seen hate in another person’s eyes. I’m not a courageous person.” Boulder Daily Camera interview, June 3, 1973

While Florence downplayed her own courage, she also continued to write about those marginalized by society. For decades, she continued to write books with marginalized main characters, including African Americans dealing with education discrimination in the American South, Indigenous Americans growing up on reservations, and early Spanish-speaking families colonizing the Southwest. She was even able to meet famous African American scientist George Washington Carver, about whom she wrote a biography.

Florence Crannell Means died November 19, 1980 in Boulder, Colorado. She and her husband Carl Means are buried at Crown Hill Cemetery in Wheat Ridge, Colorado. While most of her books are no longer widely read, The Moved Outers received a prestigious Newbery Medal and was reprinted in 1993. Florence and Carl’s daughter Eleanor Hull also went on to publish several children’s books dealing with race and social issues. Eleanor lived to be 100 and died in 2013.

Autobiography - the story of a person's life written in their own words

Marginalized - treated differently because one is different from the people in the majority

Indigenous - the earliest known inhabitants of a place and especially of a place that was colonized by a now-dominant group

Why do you think someone born in New York early in the 1900s became so interested in minorities living in very diverse places across the country?

What do you think motivated her to speak out against injustices inflicted upon these various groups?

Are there any injustices going on today that you would want to speak out against?