The Whittier and San Rafael neighborhoods' early development was influenced by the Denver fire of 1863, which prompted the institution of a city ordinance that mandated a change in the quality of construction from wooden frame to brick structures. Increased urban population, a need for quality family housing, and the emphasis on permanent brick construction combined to shape this area of Denver. The first subdivision in the area, the Case Addition, located in the northeast quadrant of the Whittier neighborhood, was filed just after the Civil War in 1868. Significant development of housing followed in the 1870s and 1880s. In February 1874, the first annexation to the city of Denver included the area of San Rafael and a portion of what is now Whittier. An early advertisement described the area as “beautifully located overlooking the city with a glorious view of the mountains.” The majority of homes were built for middle-income Anglo-Americans. Residents included carpenters, bricklayers, and metalworkers—artisans who crafted many of the architectural details of Denver’s finest homes and buildings. Those details were often incorporated in many of the smaller houses constructed in these neighborhoods.

The San Rafael neighborhood, named for San Rafael, California, is comprised of three subdivisions filed for in 1874, 1882, and 1886 respectively. The San Rafael Historic District, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, is bounded by Washington Street on the west, Downing Street on the east, and 20th Avenue through 26th Avenue on the south and north.

Whittier is named for the school that dominated the area located on the boundary of the two neighborhoods between 24th and 25th Avenues on the east side of Downing Street. The school’s name honored the nineteenth-century abolitionist poet John Greenleaf Whittier. The boundaries of Whittier neighborhood extend from York Street on the east side to Downing Street on the west end. Twenty-third Avenue marks Whittier’s southern boundary, while Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard serves as its northern edge.

Beginning with the integration of the San Rafael and Whittier neighborhoods more than one hundred years ago, episodes of segregation and integration have played out there decade by decade.

To prevent them from living in other parts of the city, African-American residents were restricted to housing in the Whittier and San Rafael neighborhoods and the adjacent Five Points neighborhood. “Color lines” were drawn through the area, restricting the habitation of races to precise streets and alleys.

Whittier and San Rafael have been racially mixed neighborhoods for more than a century and have therefore been a flashpoint for many issues. In fact, the city’s history of segregation and integration was played out in large part in these neighborhoods. While portions of that history are painful, they should not be forgotten.

Fire Station No. 3 has been an integral component of the surrounding communities since it was first organized as a professional department in 1882. The station’s original home, from 1888–1931, stands across the street from its current location and is the Wallace Simpson American Legion Post at 2563 Glenarm Place. In 1892, it became the first Denver fire station with black members and provided the only opportunity for African-Americans to serve as firefighters.

In 1895 Station No. 3 suffered a terrible tragedy when four of its members were lost while battling a hotel fire in downtown Denver. The St. James Hotel, located at 1528 Curtis Street, was considered one of Denver’s finest hotels. Company No. 3 was one of the first to reach the fire that had started in the hotel’s basement. Captain Harold Hadwell, who was white, and African-American firefighters William Brawley, Richard Dandridge, and Steve Martin worked their way across the hotel lobby to the source of the fire below. Without warning, the lobby floor collapsed. The four firefighters tumbled to their death in the basement fire. The funeral for the four men, held in the Denver Coliseum, was unlike any seen in Denver before. Four caskets, exactly alike and all treated equally, were surrounded by police officers and firefighters. Attendees filled the coliseum beyond capacity.

The original Whittier School (now demolished) consisted of a three-story red brick building facing Marion Street, with entrances on the southeast and northeast corners. The school’s grand scale, spacious central hall, and decorative elements made Whittier one of Roeschlaub’s most exuberant schools.

Roeschlaub was invited to present the plans and photographs of Whittier Elementary School at the World Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exhibition in New Orleans in 1884. In 1885, the School District Number One report noted, “the finest view in Denver . . . may be obtained from the roof . . . a board walk is provided for their accommodation.” A north wing was added in 1888, a south wing in 1894, and a gymnasium in 1934 (which remains today). In 1970, Langhart, McGuire and Hastings designed the modern building, and the original school was torn down.

The city’s first African-American teacher, Marie Anderson Greenwood, was hired by the Denver school system to teach first grade at Whittier Elementary School in 1938. She was hired under a three-year probationary agreement, with the understanding that the school system would not hire another black until she passed her probation. Her success opened the school district to many African-American teachers.

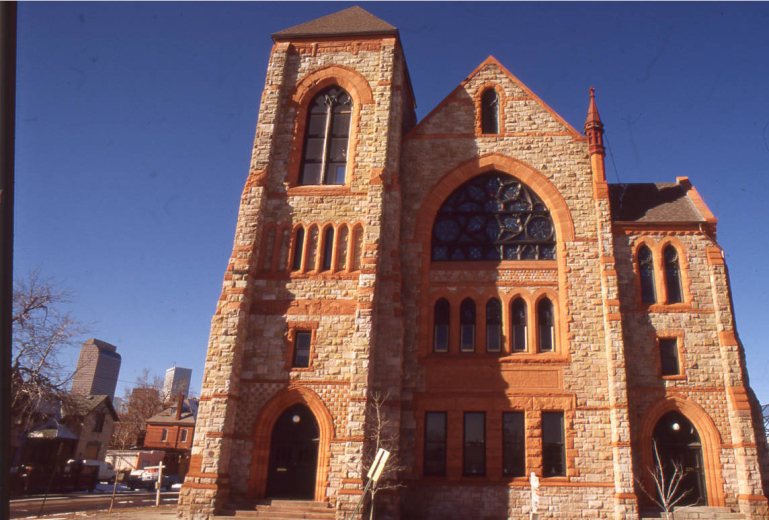

St. Ignatius Loyola

This beautiful brick Gothic Revival church was built in 1923 and dedicated in 1924. Classically arched windows soar toward the church's pinnacled roof. Modeled after a church in Cork, Ireland, St. Ignatius Loyola towers over the western edge of City Park.

St. Ignatius Loyola's parish fortunes have waxed and waned with those of the Whittier neighborhood. The congregation's numbers peaked in 1940 with approximately 1,100 families attending. Current [2004] attendance is slightly more than 300 families. St. Ignatius Loyola Catholic Church was recently listed on the National Register of Historic Places, largely due to the volunteer efforts of its congregation.

Architects Frank W. Frewen Jr. and Frederick J. Mountjoy designed the impressive structure. Frewen grew up in the Whittier neighborhood, attending Manual Trade School on Williams Street and 26th Avenue. Frewen designed approximately eighty buildings in the Denver area and was noted for his school designs. Mountjoy and Frewen jointly designed several other prominent structures in Denver, including Elbert and Park Hill Elementary Schools and the Fairmount Cemetery Communal Mausoleum.

Zion Baptist

The congregation of Zion Baptist Church was established in 1865 by freed slaves and is Denver’s oldest black congregation. Originally housed at 20th Avenue and Arapahoe Street, Zion Baptist purchased this church building in 1913. One of Zion’s most influential pastors was Wendell Theodore Liggins, who led Zion Baptist from 1941 until his death in 1991. Liggins served as chaplain for both the House of Representatives and the Senate for the State of Colorado. Zion member and Civil War veteran Rufus Felton was the first African-American teacher in the Colorado Territory.

Rev. Wendell T. Liggins, a noted orator, served as pastor from 1941 until his death in 1991. The building previously housed Calvary Baptist Church.

This building embodies typical Romanesque Revival style. It was designed by Frank J. Jackson and George F. Rivinius. The walls are massive rhyolite stone over brick in heavily rusticated horizontal bands. Most of the windows are rectangular, with round arches over a few.

Scott United Methodist Church/Sanctuary Lofts

In 1927, this church was renamed for pioneer black Methodist Bishop Isaiah B. Scott after its African-American congregation acquired the property. Originally constructed as Christ Methodist Episcopal Church, this building boasted the tallest spire in Denver in 1891. Originally constructed as Christ Methodist Episcopal Church, this beautiful stone building, built of gray rhyolite, trimmed with red sandstone, became Scott United Methodist Church in 1927 and was later sold to Greater Jerusalem Church of Christ. Since then, the building has housed a daycare, temporary employment service, and offices. In 1995 the church was remodeled into condominiums, now known as the Sanctuary Lofts. The building combines Romanesque and Gothic architectural influences.

Thirteenth Avenue Presbyterian Church

The Thirteenth Avenue Presbyterian Church was dedicated May 20, 1883 at the corner of what were then Pierpont Street and 13th Avenue (now Washington Street and 23rd Avenue). The church served the San Rafael neighborhood. The original congregation had eighty-seven charter members. The congregation grew so rapidly that by November 1883 they voted to build an addition to house the Sunday school. On December 15, 1886, the name of the church was changed to Twenty-third Avenue Presbyterian Church to reflect the renaming and renumbering of the Denver streets. The church’s asymmetrical design includes a cross-gabled roof that supports a four-story spire, which is accented by pinnacles at the four corners of the spire. The prominent gables house Gothic stained-glass windows.

Church of the Holy Redeemer/ St. Stephen's Episcopal Church

Holy Redeemer is the oldest African-American Episcopal congregation in Denver. The congregation was originally organized in 1892 as a mission, composed of Catholic whites and African-Americans who met at Emanuel Chapel at 10th Avenue and Lawrence Street. In 1931 the congregation moved to the Whittier neighborhood, eventually purchasing St. Stephens. This building was built in 1909 and designed by renowned Denver architects William E. and Arthur A. Fisher.

Holy Redeemer Episcopal Church parishioners enjoyed the services of Rev. Harry E. Rahmling for forty-six consecutive years, from 1920 to 1966. When he came to Holy Redeemer in 1920, there were only 75 parishioners; at the time of his retirement, the church boasted a membership of more than 7,000.

Reverend Rahmling was the first African-American to receive a master’s of theology degree from Iliff School of Theology and ranked second senior priest in the state of Colorado at the time of his retirement.

Architect Robert Roeschlaub designed the original Manual Training High School. The building was completed in 1894, occupying only the southwest corner of the current campus. Roeshchlaub’s design reflected the school’s curriculum: first floor—foundry, forge, and machine shop; second floor—drawing rooms, carpenter shop, and pattern shop; third floor—sewing room, cooking room, and physics and chemistry laboratories.

After a fire destroyed the original school, the present three-story building was dedicated in 1953. Manual High School is historically significant for the societal changes it contributed to Denver. Not only did the school evolve over time from being a segregated school for blacks only to an integrated school, but many of its graduates became leaders in the city.

May Cody Decker resided in the house at 2932 Lafayette Street in the Whittier neighborhood. It was built circa 1892 in a Queen Anne style and designed by Arthur Hughes. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody died in this house on January 10, 1917. Cody was a major contributor to the myth of the American West. He had a career as a Pony Express rider, army scout, Indian fighter, and buffalo meat supplier for the railroad. Cody is best remembered, however, for his Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows that toured both in the United States and abroad for two decades. He actually coined the phrase “Wild West.”

Cody visited Denver often enough to feel free to comment on the “skyscraper” Daniels and Fisher Tower. “Every time I see the new massive steel frames of skyscrapers spring into the air, I cannot but think of the time where a view of the foothills could have been obtained—and a good one, too—from any point in the city.”

Although Cody died penniless, the Rocky Mountain News reported his wife left a fortune of more than $90,000 when she passed away in Cody, Wyoming. Because of the difficulty of transporting Cody’s body during the winter to his requested burial site, he lay in state at the Colorado State Capitol until he could be interred on June 3, 1917. He chose Lookout Mountain (near present-day Golden) as his final resting place so that he might “gaze out” over the Great Plains and the Rockies. Twenty thousand people attended his burial, reaching the summit by railroad, bus, horseback, and on foot. It was reported to be the first traffic jam in the history of the state.

View of houses on E 24th Avenue, in the San Rafael Historic District of Denver, Colorado. Houses in this middle-class residential neighborhood date from the early 1870s to the 1920s. Of architectural interest is the chronological progression of the district from early woodframe and Italianate style buildings to the large and elegant Queen Anne style houses. The district also includes several terrace-style apartment buildings, two-story carriage houses, and six churches.

Babcock Row: 2337, 2343, 2349, 2361 Vine Street

Henry C. Babcock a prominent Denver businessman, purchased all of these lots in McCullough's Addition in 1879 and subsequently developed the houses using the architectural firms of Balcomb and Rice and E. Rogers.

The most interesting of the houses is the Albert Sechrist House at 2361 Vine Street. Sechrist's residence stands out among the seven Balcomb and Rice houses of the Whittier Neighborhood. The front porch pediment is decorated with floral swags and incised detail. Most unusual are the solid arched supports flanking the offset porch entry. Romanesque influences are evidenced in the narrow eyebrow dormer in the roof peak, which peers over the more prominent roof dormer, and the round top window at the front facade. Typical of Balcomb and Rice designs, this building appears to embrace the asymmetry of the Queen Anne Style.

Robert G. Balcomb and Eugene R. Rice formed their architectural partnership in 1886, designing numerous houses in the Whittier and San Rafael Neighborhoods. Their partnership was dissolved in 1897.

This duplex is a classic Queen Anne with irregular shapes, including four front-facing gables. The patterned brickwork avoids a smooth-walled appearance. The asymmetrical facade and partial front porches further break the mass of the structure.

Many Denver houses built in the 1880s are in the Queen Anne architectural style. After the Silver Crash of 1893, the Queen Anne Style was abandoned in favor of the less extravagant Foursquare Style.

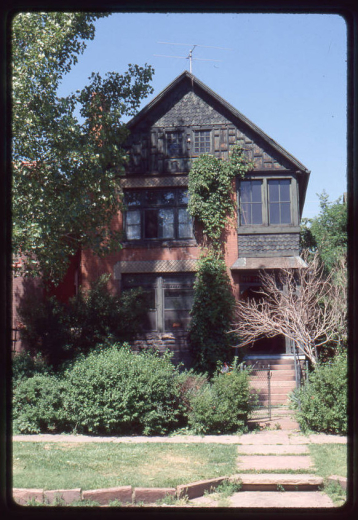

The Thomas Hornsby Ferril House at 2123 Downing Street was built in the Queen Anne Style in 1889 by architect/builders Franklin Goodnow / Hughes J. Llewellyn.

Colorado's Poet Laureate Thomas Hornsby Ferril's great-aunt, Mrs. J. N. Palmer, built this house. The first two floors are of brick and the attic story is of wood with decorative diamond-shaped shingles and latticework. Geometric East Lake trim decorates the front dormer. Ferril lived in the house from 1900 until his death in 1988. The house is now [2004] occupied by the Colorado Center for the Book, continuing the house's importance to the literary arts in the state.

Architect Goodnow was a charter member of the Colorado AIA. He designed houses through the Whittier and San Rafael Neighborhoods, including 2123 Downing Street, 2307-09 Clarkson Street, 2323-39 Race Street, and 1925 East 23rd Avenue.

McBird House

This Second Empire house was designed and built by Architects Matthew John McBird / Fleming Brothers at 2023 Lafayette Street in 1879, and moved to its current location at 2225 Downing Street in 1993 to accommodate the expanding hospital district. Denver architect Matthew John McBird occupied this residence from 1880 until his death in 1903.

Second Empire was a popular style for American houses constructed between 1860 and 1880. The distinctive roof was named for the seventeenth-century French architect François Mansart. The style dates from France's Second Empire during the reign of Napoleon III and takes its name from the period. The style was used for many public buildings in America during the Grant administration (1869-77) and is sometimes referred to as the General Grant style.

The Gebhard Mansion is generally recognized as one of Denver's finest examples of the Italianate architectural style, with its hipped roof, decorative gables, and bracketed cornice. Master builder Henry Gebhard built the house in 1883 and lived in the mansion until 1938. Gebhard was also a state legislator, and the president of Western Manufacturing Company and the Colorado Packing Provision Company. The latter company became the largest packer of pork and beef in Colorado. These days the mansion is a medical office, owned and restored by Dr. Charles Brantigan.

John Huddart was an English-educated architect whose work in Denver spanned forty years. He is recognized as one of Denver's most talented nineteenth-century architects. In his commissions Huddart combined elements of both Queen Anne and Richardsonian Romanesque styles, developing a decidedly eclectic architectural style.

This three-story brick house sports and enormous tower on the south side. The complex roofline and partial-width front porch are more classically Queen Anne, while the feeling of weight and heft of the building suggest a Richardsonian Romanesque influence.

Unverified neighborhood lore suggests the original owner of the property had a tunnel running under Humboldt Street that gave him access to a dairy barn. During Prohibition, the tunnel was said to be used for hiding illegal liquor.

2501 High Street

This lovely rusticated Castle Rock lava stone house was designed and built by master stonemason, contractor, rancher, and banker Robert Russell. Note Russell's typical use of fanciful gargoyles peering from the roofline. The walls are trimmed in red sandstone at each set of pilasters that outline the arched windows.

Byron L. Miller, a banker and realtor, commissioned the house and lived here until 1948, when the family sold the house to a Pullman conductor named Talbert Bartholomew.

Russell was born in Scotland and came to the United States at the age of seventeen. He worked as an excavator on the Panama Canal prior to moving to Denver. He died in March of 1937 and is buried in the Fairmount Communal Mausoleum.

The Neef house stands directly north of Fuller Park, Denver's second oldest park. Horace J. Fuller donated the square block of land in 1879 specifically for use as a park. During the 1880s, approximately 2,000 trees were planted by Fuller in the surrounding neighborhood.

Although technically almost a decade past the Gothic Revival period, the Neef house can arguably be described as heavily influenced by that period's style. The highly decorative vergeboards, finials, and window crowns of the Neef House, coupled with the undecorated masonry that stretches into the gables, are all characteristic elements of the Gothic Revival style as more commonly seen on wooden construction in the eastern parts of the United States. However, the architect included elements also commonly seen on Queen Annes, including the two-story front porch and classically proportioned porch columns.

Brothers Frederick and Max Neef left Germany in 1971. They moved to Colorado from St. Louis in 1872 to try their luck at the Del Norte, Colorado gold strike. Learning that the strick was not as big as they had heard, they stayed in Denver and opened a saloon. Trade was good and they expanded their business with the construction of a three-story brick building in Lower Downtown, which included a dance hall and rooms to rent on the upper floors. The Neefs sold the business in 1891 to William Fair so that they could shift focus from retail to beer brewing. Fair continued to run Neef's Hall until it closed in 1912. The Neef brothers bought the old Western Brewing Company at West 12th Avenue and Quivas Street in 1892. Their brewery was known as Neef Brothers Brewing Company, and its Gold Belt Beer became nationally known. They continued operations with their sons until Colorado voted for Prohibition in 1916. After unprofitably turning to producing "near beer," the brewery was closed and the company dissolved in 1917.

The information regarding the Whittier and the San Rafael neighborhoods are pulled primarily from a Historic Denver Guide, Whittier Neighborhood and San Rafael Historic District. There are many more entries in the Guide than are represented in this exhibit. Historic Denver, Inc. has published a number of guides for the various historic districts and building styles in Denver. These guides can be purchased at the Historic Denver, Inc. website. The guide for Whittier and San Rafael, includes more information and tours of the area. More information on the City Beautiful Movement can be found in Denver, The City Beautiful by Thomas J. Noel and Barbara S. Norgren, also available on the Historic Denver website. This blog entry explores the City Beautiful movement through the eyes of Colorado photographer Louis C. McClure.