You may be inspired to research your family history after watching “Who Do You Think You Are” or “The African-Americans: Many Rivers to Cross.” The Denver Public Library is here to help you in your quest.

Everyone begins the same.

- identify facts about those who came before you

- find their dates and places of birth, marriages, divorces, and death.

- gather the same information about your aunts and uncles and previous generations of aunts and uncles.

- A network of family and extended family members develops.

Interview family members to see what information is already known.

- A cousin may be working on a family history

- They may have newspaper clippings of weddings and anniversaries photographs and Bible records.

- They will have stories to share about their own lives and what other relatives have done in their lives.

Organize your findings using two basic forms.

Educate Yourself

Take a genealogy class. Attend the Beginners Genealogy Class the second Saturday of most months, and the Special Interest Classes the third Saturday of most months. They are free and open to everyone.

You will learn basic research methods and be introduced to various records such as home sources, interview techniques, vital, census, land, tax, cemetery, and military records.

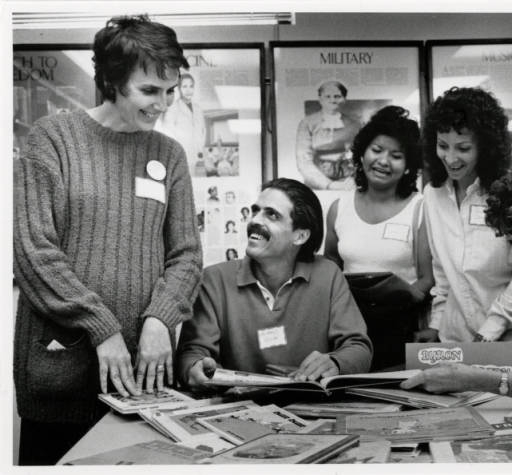

The Denver Public Library has a great genealogy collection and western local history collection. The staff is ready and waiting to help you explore your roots.

Our collection emphasizes United States genealogy.

- Explore county histories, church anniversary booklets, high school yearbooks, compiled cemetery listings, tax lists, and census records.

- Discover military records and hereditary and lineage society publications. Open compiled genealogies and family histories.

- Look at maps, atlases and place name guides. Read articles from genealogy and historical society publications such as journals, quarterlies, magazines and newsletters.

- Scroll through electronic subscription and free web sites dedicated to genealogy and history.

- Experience digital information and images from home or the library or slip on a pair of gloves and read archival and manuscript materials.

Special Collections and Archives items cannot be checked out, they will be available when you visit (unless they are being used by another researcher).

Calvary Cemetery Listing 1889-1893

Calvary Cemetery Listings are an index to lot purchases in Denver’s first Roman Catholic Cemetery from

1889 to 1893.

Historical background and a list of current cemeteries.

Fairmount Sexton Records 1891 – 1953, Fairmount Cemetery, Denver, Colorado

The Fairmount Sexton Records 1891–1953 are arranged in rough “alphabetical order” by age, sex, race, date of burial, and other information.

Riverside Cemetery Burial Register Index, 1876 - 1963

The index includes date of burial, name of deceased, age, location of burial and some additional information.

Members of the Grand Army of the Republic from Colorado who were buried in the G.A.R. burial ground at Riverside Cemetery. Includes those buried and later removed from Calvary [Catholic], Hebrew, and Old City [Mount Prospect] cemeteries, in Denver.

When you've gathered as much information as seems possible through your family interviews and vital records searches, it's time to consider more complex sources of information. There are a number of options for the researcher: military records, census schedules, probate records, local history sources, immigration information, land and tax records, among others.

The census is the backbone of American genealogical research. The U.S. government has been collecting census data every 10 years since 1790. You have a window into your family’s home every ten years. Due to privacy laws, it takes 72 years after a census has been recorded before the information is opened to the public. The 1940 census is the last census open for researchers.

It's a good idea to start with the 1940 census and work backwards, trying to locate an individual or a family in each census.

Expect to find variations in the answers given from decade to decade on the census. Year or place of birth may change, the given name might be slightly different, and anything is possible.

Keep in mind that the surname spelling may be far different from what you expect. The spelling could have changed over the years, or, more likely, the census taker spelled the name as she heard it, not as the family spelled it.

Your Guide to the Federal Census for Genealogists, Researchers, and Family Historians by Kathleen W. Hinckley was published in 2002 by Betterway Books (G317.3 H582yo 2002). It is still the best introduction to the federal census for any researcher.

Land records are the written evidence of people’s entitlement to land and property and goes back in time further than virtually any other type of record a genealogist might use. In America, land and property records apply to more people than any other type of written record. Land records will locate an ancestor in a particular area and allow further research of other records in the area.

Occasionally a land record will contain valuable genealogical information, perhaps stating family relationships, or listing children, or mentioning a previous place of residence.

There is no one central location for land records. They will be found at federal, state, and local government agencies. You need, at least, the name of the county in which property was owned.

To search for homestead records, you will need legal description of the homesteaded land.

To better understand land records you will want to consult Land and Property Research in the United States by E. Wade Hone (G929.1072073 H756Lan).

You may also wish to review the National Archives & Records Administration's page on land records and search the Bureau of Land Management's General Land Office Records database.

The immigration process produced a number of records of value to the genealogist. The two types most frequently sought out are ships passenger lists and naturalization papers.

After 1820, ship captains were required to file lists of those passengers disembarking at a U.S. port. These lists are held by the National Archives. Many passenger lists are available through AncestryLibraryEdition.

They Came in Ships by John Philip Colletta published in 1989 by Ancestry (G929.07073 C689th) is an easy introduction to passenger lists.

Images of the U.S. Federal Census from 1790 forward, the American Genealogical Biographical Index, immigration lists and over 9,000 more databases.

People could be naturalized in any court of record until 1906. These records are to be found in various courts, archives, and historical societies. After 1906 naturalizations were supposed to take place in the Federal District Courts. Following are descriptions of three of the most common immigration records. Remember that these might contain valuable information, but it's just as possible that they will list only an ancestor’s name.

Declaration of Intention is sometimes called “first papers”: this document was filed some years prior to naturalization, was the first step in the process. First papers might contain birthplace, personal description, and port and date of entry, among other information.

Petition for Naturalization is also known as “final papers”: this document was filed at the time of naturalization, and might contain such information as date of filing of first papers, name and age of spouse and children, last foreign residence, date and port of entry.

Certificate of Naturalization is the last step in the process. It might also contain the type of information found in the first and final papers.

For further you may enjoy: Guide to Naturalization Records of the United States by Christina K. Schaefer published in 1997 by Genealogical Publishing (G929.373 S294gu) or How to Find Naturalization Records by Elaine Alexander published in 2004 by Delphic Press (G929.1072073 A374ho 2004).

Bibliography

If you would like to do further reading on the subject, here is a list of books to help in your research. There are also circulating copies of these and many other titles throughout the DPL system.