In 1887, Baron Allois Gullaume Engine von Winckler designed the original Park Hill development on 32 acres of land he owned in northeast Denver. As the neighborhood grew, settlers from many nations, including England, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, and Italy, moved into the neighborhood, as did African Americans. Today, both South and North Park Hill remain diverse communities representing many ethnic backgrounds.

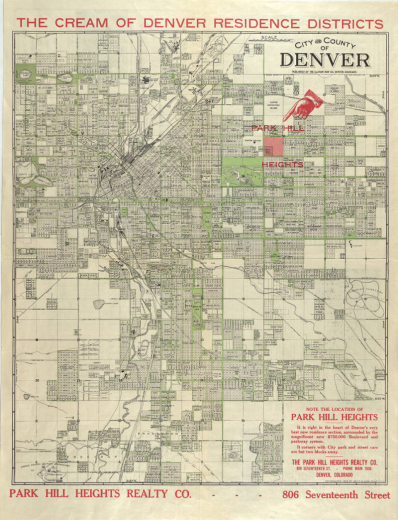

Park Hill traces its origins as a community to Baron Allois Gillaume Eugene A. von Winckler, who arrived in Denver in 1884. Like his contemporary and fellow Prussian, Baron Walter von Richthofen, Winckler established himself in east Denver. Taking Richthofen's Montclair neighborhood as his inspiration, Winckler purchased land east of Denver's City Park and north of his countryman's development, and platted Park Hill in 1887. For a developer, the eccentric baron was surprisingly intolerant of his neighbors, and preferred the company of Walter Cox, Denver's pound master and dogcatcher. After Winckler took his own life in 1898, his property soon became available to other developers.

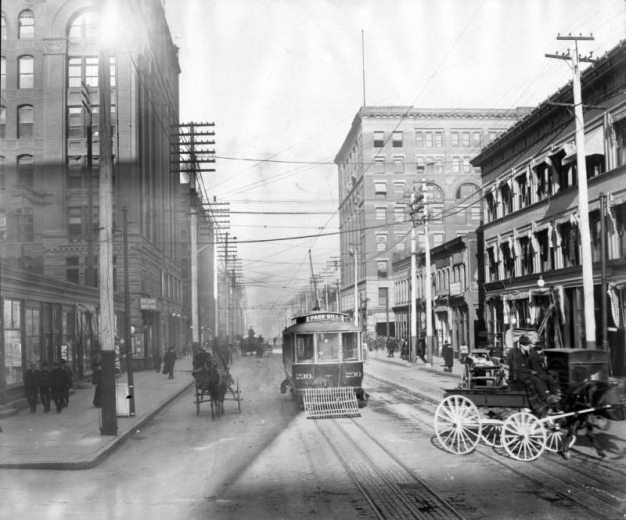

Those developers began the creation of Park Hill as a residential neighborhood, making over what had been a setting for dairies and brickyards into tree-lined streets with attractive homes, offering a quiet life removed from the city. Early developers presented the immediately adjacent City Park not merely as a place of relaxation and leisure, but also as a buffer between residents and a city often characterized as a place of noise, hustle, and iniquity. Developers also drew a contrast with Capitol Hill, which they represented as a neighborhood then in decline. In most respects, Park Hill's early development was similar to so-called streetcar suburbs established in other turn-of-the-century American cities. As urban populations increased, public and private interests built transportation systems for communities at the edges of cities, allowing urban centers to extend their bounds and pursue growth rather than address the problems of density. The Park Railway Company, established in 1888, operated until 1899 when the Denver Tramway Company absorbed it. By the early 1930s, Park Hill had become an automobile suburb, as the majority of Denver commuters now made their way to work by private car.

The development of Greater Park Hill over the course of several decades ensured a significant diversity in its streets and the architecture of its homes. The twentieth century would see the most significant building in Park Hill during the 1920s and 30s, and again in the 1940s and 50s to meet the post-World War II demand for housing, especially in the vicinity of Stapleton airport. Consequently, Park Hill's residential styles range from various Victorian forms to the Arts and Crafts homes of the early twentieth century, to modest mid-century homes constructed for new postwar families.

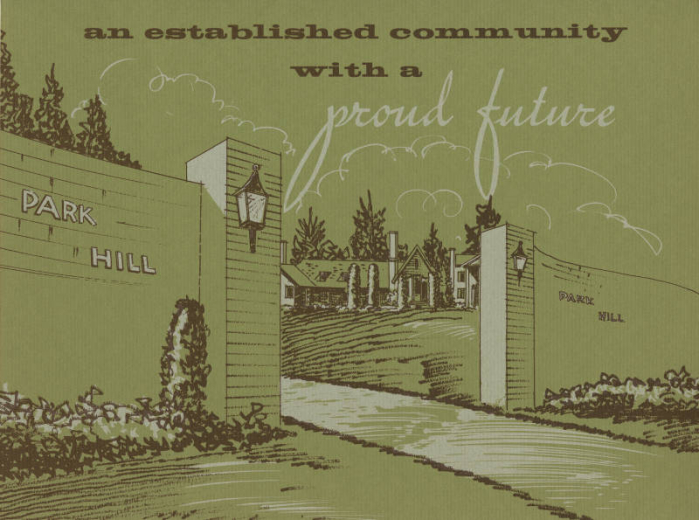

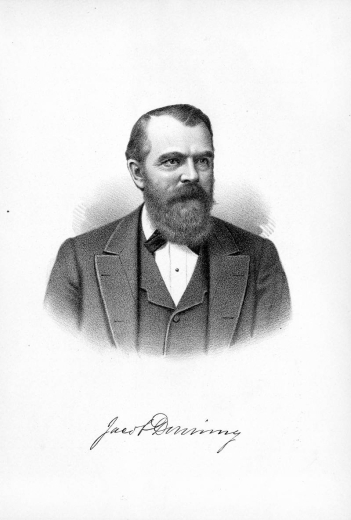

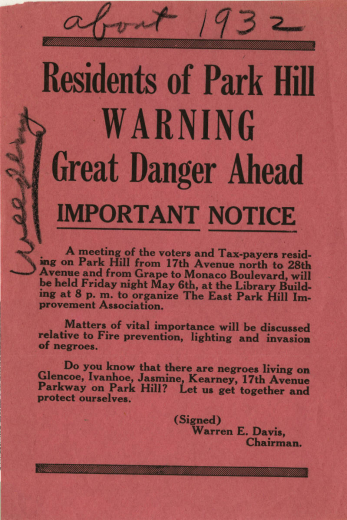

From the early 1920s, Park Hill was an established neighborhood, one frequently characterized as among Denver's most desirable places to live. Developers presented the neighborhood not merely as a place to call home, but as a reflection of accomplishment and affluence, and they appealed to the aspirations of prospective homeowners. Similar appeals continued throughout much of the twentieth century. A brochure published in the 1960s to promote the neighborhood captured the appeal: "In Park Hill you can be pardoned for feeling quietly pleased with yourself... just a bit smug." Park Hill developers also took steps to assure prospective residents that their community would suffer no future decline or the encroachment of whatever, or whomever, they might deem undesirable. Like other Denver neighborhoods, including Montclair, South Denver, Highlands, and Berkeley, Park Hill developers established restrictive covenants and limited the use and nature of residential neighborhoods and homes. To the west, Jacob W. Downing's "Downington" included racial restrictions, and by the early twentieth century, Downing Street marked a racial divide between black and white in Denver.

In the years immediately after World War II, Denver's population growth and the increased demand for housing created the basis for the conflict central to Park Hill's contemporary identity. Middle-class African Americans, many from the Five Points neighborhood, began to purchase homes to the east, moving closer to the almost exclusively white Park Hill neighborhood. Within a few years, black families seeking the same quality of life as their white neighbors were poised to move into Park Hill. Unscrupulous realtors used the racial divide to their advantage, steering black families onto streets where their arrival precipitated white flight. The practice, known as blockbusting, provided realtors with a flurry of sales. Race also stood between prospective black homeowners and a Park Hill home, as they faced banks unwilling to lend and realtors unwilling to sell on particular streets. George Morrison, Jr. and his wife, Marion, sought a home in Park Hill in 1958, and struggled to secure a mortgage from a local bank. Morrison's familiarity with mortgage law and his family's relative affluence eventually secured them both a mortgage and a home. Nonetheless, fear took hold, and flight followed. "The 'for sale' signs sprouted like dandelions," Morrison recalled in 1991, evoking a familiar image of white flight from Park Hill's northern streets.

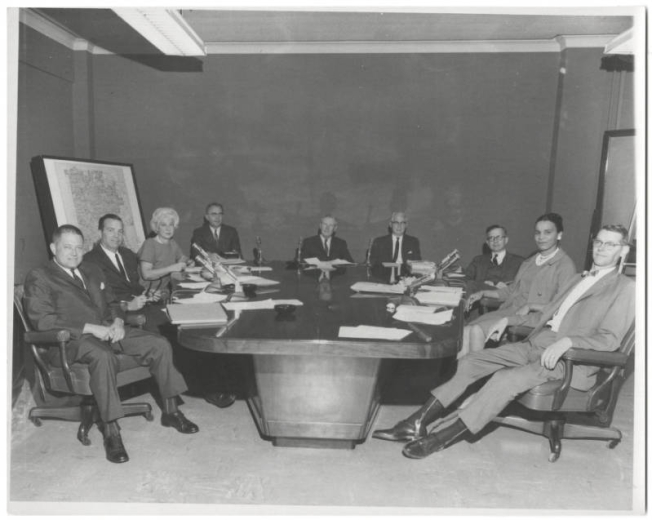

Some Park Hill residents organized to seek an orderly integration of their neighborhood. In 1960, a coalition of Park Hill churches, their congregants, and other neighborhood residents met at the Montview Presbyterian Church. Together, they established the Park Hill Action Committee, later to become the Greater Park Hill Community, Incorporated, which would become almost synonymous with the neighborhood and its civic efforts. Leah Dillard, whose family purchased a home on Ash Street, found some neighbors less than receptive to the arrival of an African American family. But the Dillards did find neighbors who welcomed them, including Father Marion Hammond at St. Thomas Episcopal Church, and their fellow congregants, Bea and Art Branscombe. For their part, the Branscombes were determined to create an inclusive Park Hill, in no small measure because of their own experiences. As Art Branscombe explained at the time of his wife's death in 2002, Bea had fled Austria after its annexation by Nazi Germany, and the trauma forever shaped her perspective. "When she got here," he recalled, "she said, 'I'm not going to move again.'" For decades thereafter, the Branscombes remained active in the life and community of Park Hill, and came to serve as its unofficial historians.

Park Hill Action Committee and its successor, Greater Park Hill Community, Incorporated, organized neighborhood events to foster awareness and address issues that threatened to divide the community throughout the 1960s and 70s. Conflict over the integration of Park Hill's residential streets soon spilled over to the larger question of Denver's segregated public schools. In the mid-1960s, the movement for school integration found a champion in Rachel Noel, a Park Hill resident, whose single term on the Denver School Board would see her put in motion events that would forever alter Denver's public schools. Noel's 1968 resolution, a call for a plan to integrate Denver's schools, initially carried the School Board, only to lose support after a subsequent election. That reversal precipitated a lawsuit that eventually saw court-ordered integration.

In recent decades, as the conflicts of the 1960s and 70s receded, the Park Hill community continued to demonstrate notable activism on a variety of quality-of-life issues, such as the disposition of toxic waste, flight paths at Stapleton airport, and recurrent experiences with violence, crime, and gang activity. A legacy of integration has left many residents of Park Hill with an understandable pride in the tradition of tolerance and diversity in their community. At the same time, differences and divisions have remained, sometimes making it difficult for residents to reconcile their present circumstances with accomplishments of the past. From the early 1970s to today, the unfulfilled promise of an integrated Greater Park Hill has proved a disappointment to some residents, who point to a community still divided by race and class. Census figures from 2000 demonstrate a racial divide within Greater Park Hill, with Northeast Park Hill's residents predominantly African American (68.5%) and a now substantial and growing Latino population (23.8%). North Park Hill's residents remain predominantly African American (56%), but with Latino and non-Latino/white populations showing a modest increase in recent decades. South Park Hill remains predominantly white (74.6%), with a Latino population that has nearly doubled since 1980, and an African American population that has declined since 1990. Similarly, census figures also demonstrate significant differences in wealth amongst the neighborhoods of Greater Park Hill. In 2000, the average income for Northeast Park Hill households ($37,468) was notably smaller than households in North Park Hill ($58,392) and Denver as a whole ($55,129), and less than half of South Park Hill households ($88,479). Nearly one-quarter of all Northeast Park Hill residents lived in poverty (23.8%) in 2000, a proportion much higher than in Denver (14.3%), North Park Hill (9.4%), or South Park Hill (6.9%).

Regardless of promises realized only in part, or not at all, pride in Park Hill runs deep. Annual tours, civic and neighborhood events, and a near-certain response to any challenge to safety or security characterize Park Hill's community life. One former resident, the NBA star Chauncey Billups, wears his love for his neighborhood on his sleeve, with "King of Park Hill" tattooed on his arm. When Billups played in the 2006 NBA All Star game, he dedicated his effort to his home state, but saved his heart for his neighborhood. "I'm representing the state of Colorado," he remarked, "even though my pride is in Park Hill."

Greater Park Hill is comprised of three smaller neighborhoods, known as Northeast Park Hill, North Park Hill, and South Park Hill. Greater Park Hill's boundaries are Colfax Avenue on the south, Colorado Boulevard on the west, 52nd Avenue on the north, and Quebec Street and Syracuse Street on the east. With common east and west boundaries, Northeast Park Hill and North Park Hill share a boundary with Martin Luther King Avenue, while North Park Hill and South Park Hill share a boundary with 23rd Avenue. Park Hill derives its name from its proximity to Denver's Central Park, and its place on the gentle rise onto the high plains east of the Platte River Valley.

Margaret Evans, wife of Territorial Governor John Evans, realized that Colorado had thousands of poorly housed or homeless children. In 1876, she, Elizabeth Byers, Elizabeth Iliff Warren, and other women formed the Denver Orphan’s Home (renamed the Denver Children’s Home in 1962), as the first annual report stated, “Take little children by the hand and safely guide to honorable manhood and womanhood the little feet which might else go far astray and help to swell the annals of crime and wretchedness and degradation.”

In 1902, the Denver Orphan’s Home moved to its current home at 1501 Albion. One hundred thirty children, ages three to twelve, moved in. A basement baby ward provided care for infants, while the third floor included an infirmary. With various additions, the home is now a fifty-room complex, including a playground. Numerous large windows brighten the red brick, sandstone-trimmed residence.

The Denver Children’s Home provides food, shelter, clothing, medical care, and education for children. Dr. Skip Barber, director of the Children’s Home, reported in 2001: “Today we have sixty-two adolescent residents daily and last year we also opened a group home for eight more around the corner. We also treat more than 150 outpatient kids every day and do outreach to communities throughout the metro area. As orphans are increasingly placed with families, the Denver Children’s Home focuses on treating emotionally distressed children and adolescents. We launched outpatient services in 1987, an after-school program in 1989, intensive in-home programs in 1995, and a day treatment center at Highlands Ranch in 2000.” Thanks to this home, thousands of Denver’s children have had a second chance at a nurturing start.

Noel, Thomas J., and William J. Hansen. The Park Hill Neighborhood. Denver, CO: Historic Denver, 2002. Print.

Park Hillers quickly outgrew the two-room frame Park School built at the northwest corner of 18th and Forest in 1894. The 1901 replacement, a much more elegant and substantial structure, was renamed Park Hill School in 1904. It served eighty-six children with three vigilant teachers and included outdoor privies and a hitching post for horses.

The large, three-story 1912 addition brought the fresh outside air indoors with its numerous windows, especially those facing south. The windows remained open even in the winter as an inducement for the students to work harder.

The three-story school wears a stuccoed light skin, red tile roof, and curvilinear parapets of the Spanish Colonial Revival style. In 1928, Mountjoy & Frewan added a gymnasium on the west and an auditorium on the east, which matched the stucco building mass, terracotta detail, and red tile roof of the original 1901 school. After World War II, Park Hill became the most crowded elementary in the Denver Public School system, with over 1,060 children by 1948. Architects Phillips-Carter-Reister designed the 1969 kindergarten wing and a cafeteria.

Longevity, social history, and outstanding architectural elements such as the medallion busts of Beethoven and Shakespeare in the florid terra-cotta trim gained this school a Denver Landmark designation in 1994.

Built when this area contained little besides prairie dog villages, the school and its playing fields occupy 4 full blocks between 26th and 25th Avenues and Kearney and Holly Streets. It sits on the site of the Ezra M. Bell estate, which included a three-story Victorian house whose immense grounds were later developed as Park Hill’s Bell Park and Belmont Subdivisions.

The school was first named Holly Junior High School and later called Park Hill Junior High School, and then Smiley Middle School. Now called Smiley Campus - McAuliffe International School , it honors Dr. William H. Smiley, a popular Denver Public School superintendent from 1912 to 1924. In 1969, Smiley became the first desegregated junior high school in Denver as a result of the Keyes v. DPS case.

Its original three-story western facade has a crenelated parapet with a dominant Jacobethan entry arch and is brightened by numerous windows overlooking the city and the mountains. The 1949, a $375,000 east wing almost doubled the size of the school with sixteen new classrooms, a music room, a gymnasium, and an expanded cafeteria for a population that peaked at about 1,900 students in the 1960s.

Architecturally, various shades of red brick are set in contrasting buff-colored cement and enriched with light terra-cotta ornament sheath this Tudor Revival school. The Tudor theme is continued inside with a dark oak finish and Tudor ornament in the form of roses, shields, and banners. The distinctive octagonal, crenelated towers are capped by elaborate domes whose paneling, curved roofs, and finials are accentuated by green and white glazed terra-cotta.

Noel, Thomas J., and William J. Hansen. The Park Hill Neighborhood. Denver, CO: Historic Denver, 2002. Print.

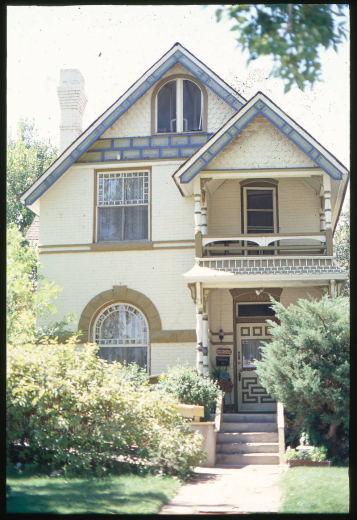

“This was all rural and there was nothing east of us,” recalls Helen Harper, who was raised in what may be Park Hill’s oldest remaining house. “We were in the city yet so isolated…We had city water, but didn’t get electricity until 1921…”

Jay A. Robinson, the first person to live here, was described by Denver city directories as a grocer and “inventor.” The Robinsons’ place lay on the edge of John Cook, Jr.’s 1880s residential development, which stretched west across Colorado Boulevard. A May 5, 1889, full-page advertisement for Cook’s Addition in The Denver Republican touted “A nice class of houses.”

The Robinson and McCoy Houses and a few other quaint Victorian structures are remnants of the days when the Cook Addition streetcar connected these prairie pioneers with downtown. Cook powered his streetcar with a horse, which strained to pull the car up East 34th Avenue to the street named after him. From there, passengers walked to their homes and the horse stepped happily into a cart attached to the streetcar for a gravity-powered ride back to Denver.

In 1913, Helen Harper’s grandparents, James and Mary Roe, bought the three-bedroom Robinson House with its 12-foot ceilings. They farmed here, building a now-gone barn, chicken coop, and other outbuildings.

Their home’s Queen Anne detailing includes the original two-story gingerbread porch, an arched window with stone surround and keystone, an ornamental bargeboard above fish-scale shingle work, and a tall corbelled chimney. The romance of this residence, with its garden and rural air, enhanced what was Kate’s Restaurant from 1983 - 2011.

Its beautiful original Queen Anne detailing has prompted Greater Park Hill Community, Inc., to nominate it for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places.

Noel, Thomas J., and William J. Hansen. The Park Hill Neighborhood. Denver, CO: Historic Denver, 2002. Print.

Before the neighborhood became residential, Park Hill’s grasslands fed the cattle herds of several dairy farms. The original Park Hill Dairy was operated by the Obrecht family, whose 1890 Queen Anne home survives at 17th Avenue and Glencoe. Buildings survive from the Quinn Brothers Dairy at 5335 36th Avenue and 3604 Glencoe Street, the Johnson Dairy Farm at 3339 Olive Street, and the North Capitol Hill Dairy at 3327 Olive Street. Larger dairy operations also thrived. The City Park Dairy on the north side of City Park from 1899 to 1908 became City Park Golf Course. The huge London Dairy would eventually become Denver’s Stapleton Airport.

The Park Hill Golf Club opened in 1932 on what had been the Clayton College Dairy Farm and the original Lowry Airport, whose runway became the No. 6 fairway. This city-owned golf course, clubhouse, restaurant, and lounge are open to the public seven days a week. The clubhouse at 4141 East 35th Avenue is a sleek, low-slung, earth-sheltered complex replacing an old Tudor-style house. The swanky dining room with its fireplace and picture windows overlooking the golf course makes the clubhouse one of Park Hill’s special places.

Besides a flourishing dairy industry, Park Hill had clay soil that attracted brickmakers. The largest operation was the Farrey Brickyards at 34th Avenue and Dahlia Street.

Park Hill also became the home of Denver’s fledgling aeronautical community. Colorado’s first commercial airport, Curtis Humphrey Field at 26th Avenue and Oneida Street, began offering regional passenger air service in 1919 aboard open-cockpit Curtis Jenny biplanes. Other scattered airfields soon followed. Lowry Field opened in 1924 on 120 acres north of 38th and Dahlia as the Colorado Air National Guard Training Center. The flag was finally lowered at the original Lowry Field in 1938 when it relocated to the new Lowry Air Base on the east side of Quebec Street.

Noel, Thomas J., and William J. Hansen. The Park Hill Neighborhood. Denver, CO: Historic Denver, 2002. Print.

Architect Harry James Manning made St. Thomas Episcopal Church one of Denver’s best examples of the Spanish Colonial Revival mode with a fabulous Churrigueresque entry surrounded by cast stone. A triple-arch bell tower, stucco walls, and red tile roof distinguish this church, which, with its auxiliary buildings and cloister, frames a lovely enclosed courtyard. The Mission-style interior features a wood-beamed, open-truss nave. Shields of the twelve apostles are depicted in the handmade tile inserted in the reredos on each side of the main altar.

Social activism, as well as outstanding architecture, has distinguished one of Denver’s first racially integrated churches, which was also one of the first to give women and girls roles as clerics and acolytes.

This outstanding example of Spanish Colonial Revival-style architecture became Park Hill’s first officially designated Denver Landmark in 1977. Manning’s 1929–1930 remodeling and subsequent additions have erased the small, modest brick church erected here in 1908.

The Reverend Alexander T. Rankin, Denver’s pioneer Presbyterian minister, arrived in the dusty, godless town on July 31, 1860. After meeting in downtown halls and in small churches, Presbyterians finally found a beautiful, permanent home in 1892 when they built Central Presbyterian Church at East 17th Avenue and Sherman Street. Frank Edbrooke, Colorado’s premier nineteenth-century architect, used red sandstone for this magnificent Romanesque Revival edifice that is crowned by 136-foot-high, square belfry Romanesque arches. Even with seating for 1,200 people, Central could not hold everyone.

In 1900, Presbyterians decided to build a new church in northeast Denver’s Park Hill neighborhood. The thirty-one original members erected a wooden-floored, canvas tent tabernacle in 1902. They replaced it the following year with the 1893 Park School, a secondhand frame building bought for $500 and hauled to the site.

In 1910, Montview Presbyterians built a chapel, using rhyolite stones from the demolished old Central Presbyterian Church at 18th and Champa downtown. This chapel became the east wing of the large new church built in 1918 of pink and gray rhyolite from Castle Rock with its distinctive three-story corner square tower with a castellated parapet. The 1926 education wing, containing many classrooms, a kitchen, a dining room, and a gym, used the same polychromatic rhyolite as the 1918 church.

Dr. Arthur Miller, the pastor of Montview from 1947 to 1967, presided over a period of tremendous growth. The sanctuary was expanded to the south in 1958, using a plan by Chicago architect Edward F. Jansen. The church’s many additions, despite the use of both Romanesque and Gothic elements, harmonize because of the consistent use of the same rhyolite stone in soft shades of gray, tan, and rose.

Even more impressive than its architecture is Montview’s outreach to the community. Among the many groups to find a home at Montview over the years was the Denver League of Women Voters. Montview opened a community preschool in 1964, where parents could volunteer as helpers instead of paying tuition, as well as Montview Garden Columbarium (1977), Montview Peace Garden (1990), and a neighborhood playground (1995). For its 2002 centennial, Montview sent missions to Mexico and Nepal.

Montview remains socially active, befitting an institution that led the way in organizing parishioners and nearby churches to quell racial tensions. At the height of Park Hill’s black-white crisis, Montview brought in Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., to preach to a crowd that overflowed onto the boulevard out front.

Father Fred McDonough rode his bicycle around the neighborhood in 1912 to organize Park Hill Catholics. He gained a new parish, which initially met for Mass in the original Park Hill Methodist Episcopal Church at 23rd and Dexter.

The baby parish built a Neoclassical, gray brick, three-story chapel rectory-parish hall, adorned with Corinthian pilasters, in 1913. It is now the elementary school. During the prosperous 1920s, the growing parish commissioned Denver architect Harry James Manning to design a $250,000 Gothic church with twin spires soaring over Montview Boulevard. The Great Depression killed this cathedral-sized fantasy. Manning died in 1933 and his associate, William F. Andres, scaled back the project considerably. The present one-story church opened in 1935.

Blessed Sacrament remains an interesting example of Gothic Revival with its abbreviated front towers, square-cut, ashlar limestone walls, rich but miniature Gothic stained-glass windows, slit windows, and mini-buttresses. Further additions included a parish school, the 1923 rectory at 4930 Montview just east of the church, and a 1942 convent (now a Park Hill residence) at 1901 Eudora to house the ten sisters teaching grade school. The $225,000 Machebeuf Junior High School was completed in 1951 and named for Denver’s pioneer missionary priest and the first bishop of Colorado, Joseph Projectus Machebeuf. Another $250,000 later in 1958, Machebeuf High School opened. After the high school moved to the Lowry neighborhood in 2000, its former building became part of the Blessed Sacrament Elementary and Middle School.

Park Hill Methodist Episcopal Church started out in 1911 in a tent tabernacle at 23rd and Dexter. After this twenty-lot site on Montview was purchased for $15,000 in 1921, William N. Bowman and Company designed the church, completed for 1924 Christmas services.

The L-shaped, two-story structure faces the southwest sun, which shines on the Spanish Mission Revival-style, four-story, central domed bell tower, and the two-story wings with curvilinear parapets. The 500-seat sanctuary features stained-glass windows illustrating Bible stories and a magnificent pipe organ built by the M. P. Moller Company of Hagerstown, Maryland.

By 1956, a thriving congregation peaked at more than 2,500 members and built a much larger, beige brick, $689,000 sanctuary attached to the east side of the original complex. Head Pastor J. Carlton Babbs, who welcomed blacks into the neighborhood and into this church at a time when many did not, is honored by the Babbs Memorial Chapel.

Reflecting Park Hill’s ethnic diversity, this church has had black, Hispanic, and Korean pastors. Looking forward to the next generation, Park Hill United Methodist has focused on its Children’s Center, which opened in 1981 in the original education wing. The center, which operates on an annual budget of $665,000, offers preschool, daycare, and kindergarten to more than 135 students.

Noel, Thomas J., and William J. Hansen. The Park Hill Neighborhood. Denver, CO: Historic Denver, 2002. Print.

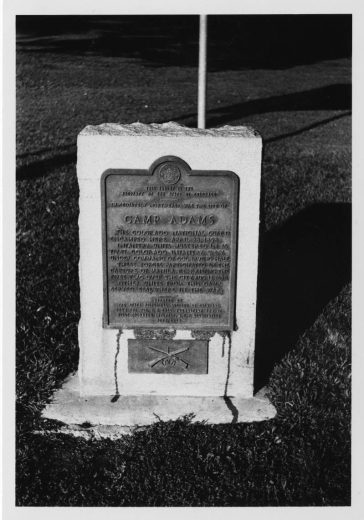

In April 1898, President McKinley declared that the United States was at war with Spain. The Spanish-American War, which was mainly fought for Cuban independence, lasted only 10 weeks with a U.S. victory. The Treaty of Paris, signed on December 10, 1898, gave the U.S. temporary control of Cuba and colonial authority of over Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. The treaty resulted in the purchase of the Philippines for $20 million dollars by the United States. The Philippine-American War between the Philippines and the United States occurred after the First Philippine Republic tried to gain independence following annexation by the U.S. The war began on June 2, 1899, and ended on July 4, 1902, after President Emilio Aguinaldo’s surrender.

In Colorado, Governor Alva Adams was the first governor to lead the state during a national war. President McKinley requested that Colorado provide one regiment of infantry and two troops of cavalry to support the war effort. On April 29, 1898, the Colorado Guard was mobilized for service in the Spanish-American War. 1400 men were activated into the First Colorado Volunteer Infantry. Due to a housing shortage, a military camp named after Adams was established on land donated by Baron Winckler in City Park. The camp was located northeast of the park, on the east side of Colorado Boulevard between 25th and 26th avenues. On May 17 after two weeks of training and enduring harsh weather conditions, the regiment sailed for the Philippines to fight the Philppine-American War. Led by Colonel Irving Hale, they participated in numerous battles and played a large role in the capture of Manila. Captain Alexander M. Brooks of Denver, Colorado raised the Stars and Stripes over captured Manila on August 13, 1898. The war had actually ended the day before the Manila attack. The regiment spent several months on guard duty in the Philippines, and went home exactly one year after its arrival. Twelve men were killed in action and another thirty-four died from disease and wounds received in battle. A Spanish American War memorial was created in City Park featuring a gazebo, flower garden, and statue. The site of Camp Alva Adams was marked with a tablet in June, 1954. Our C Photo Album 255 contains 22 images from the Spanish-American War in the Philippines.

Enlarging a basic Foursquare plan, this house has an expansive full-length front porch with distinctive Craftsman brackets, and was designed by William A. Fisher. Terra-cotta diamonds in the brick porch posts and recessed panels in the second-story facade are among the few ornaments in this buff brick residence.

Anyone peeping through that still strange-looking window in the early hours of January 13, 1917, might have witnessed one of Denver’s most titillating society murders. Five years before, socialite Stella Newton Britton Moore left her daughter and husband, a man twice her age, to elope with the family chauffeur, John Smith. His gambling, drunkenness, and womanizing soon depleted her resources and soured their marriage. She left him and returned to her daughter and the home of her former husband. Armed and drunk, Smith forced his way into the house where, after enduring hours of his physical abuse and indignations, Stella shot him with two different pistols, including one she had secreted beneath her pillow. The second shot through the mouth when he twitched prompted murder charges.

Her ex-husband hired psychiatric experts to defend her on grounds of temporary insanity and self-defense. After a long, lurid, and sensational trial, from which women were barred over the protests of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, the jury took just fifteen minutes to acquit Stella in one of Denver’s earliest successful spousal abuse defenses.

Noel, Thomas J., and William J. Hansen. The Park Hill Neighborhood. Denver, CO: Historic Denver, 2002. Print.

This stylish branch of the Denver Public Library matches Montview Boulevard’s distinguished residential designs. A one-story Carnegie Foundation-funded library with a basement auditorium, it wears an entry cartouche with the lamp of learning commemorating Andrew Carnegie’s slogan, “Let There Be Light.”

This library was originally designed by Merrill H. and Burnham Hoyt, renowned Denver architects. The cornice, trim, and exterior decorations are cast stone with rough-troweled cement hiding the brick walls. This stucco-like skin along with the red Spanish roof tiles, coffered eaves, and wrought-iron entry lamps suggests a Mediterranean air enriched by such details as the acanthus leaf balustrade motif separating the clerestory windows. Leaded, diamond pane windows, wrought-iron and glass globe reading lamps, and built-in bookcases and window-bay seating adorn the single large interior room with its richly textured walls and beamed ceiling. The breast of the cast stone fireplace is adorned with a bas-relief ship from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, by Denver sculptor Robert Garrison.

Noel, Thomas J., and William J. Hansen. The Park Hill Neighborhood. Denver, CO: Historic Denver, 2002. Print.

The Pauline Robinson Branch Library sits at the corner of East 33rd Avenue and Holly Street. Prior to the passage of a city bond issue approved in 1990, many heavily-minority communities like Northeast Park Hill had only a small leased storefront to serve as the local library. With the passage of the bond, Denver Public Library was able to construct a sleek, modern structure with plenty of room for books, programming, and computer access. It was designed by architect Bertram Bruton and named for the first African-American librarian in Denver.

Pauline Short Robinson grew up at the height of anti-black bigotry in Denver. She remembered being forced to sit only in the balcony at Elitch Theater and being denied access to restaurants downtown. After earning a degree in education, Denver Public Schools superintendent, Archie Threlkeld told her that he, “wasn't interested in hiring negroes.” She rebelled against this toxic bigotry by becoming the first African-American library student to graduate from the University of Denver and eventually served Denver Public Library until her retirement in 1979. In 1996, she was able to see the opening of the branch named in her honor and expressed pride and joy at the beautiful new space designed to serve the community.

Stapleton International Airport was located next to the Park Hill neighborhood of Denver, Colorado, and was an important air transportation center and airline hub from 1929 to 1995. It was decommissioned and replaced by a new airport, Denver International Airport (DIA). The site is now the award-winning redeveloped Stapleton neighborhood, one of the largest new urbanist projects in the United States. Stapleton served as a major air hub at various times for TWA, Peoples Express, Frontier Airlines, and Western Airlines as well as for Continental Airlines and United Airlines, the latter of which had the largest operations at the airport.

Stapleton was opened on October 17, 1929, as Denver Municipal Airport, which was later renamed Stapleton Airfield after expansion in 1944. The renaming was in honor of Benjamin F. Stapleton, the city's mayor at various times from 1923 to 1947. As airline deregulation took hold, Denver’s air traffic increased, and airplane congestion and passenger numbers made Stapleton ill-equipped to handle future passenger and airline growth.

By the 1980s, plans were underway to replace Stapleton with a new airport. A major impetus for a new airport was a lawsuit over aircraft noise, brought by residents of the nearby Park Hill community. While Stapleton was a rich part of the history of Park Hill, parts of the neighborhood were directly under the takeoff and landing paths of aircraft. Airline traffic, noise, and public opinion eventually made the airport untenable and spelled its demise. The Colorado General Assembly established a deal in 1985 to annex a plot of land in Adams County into the city of Denver and use it to build a new airport. Adams County voters approved the plan in 1988, and Denver voters approved the plan in a referendum in 1989.

On February 27, 1995, a Continental Airlines flight to London Gatwick was the last commercial flight to take off from the airport. Stapleton was closed later that evening and Denver International Airport opened the next morning. All of Stapleton's airport infrastructure has been removed except for the control tower and a parking structure which remain standing as a reminder of the site's former days as the premier airport of the Rocky Mountain West.

Greater Park Hill Community (GPHC) was founded in response to the paranoia that swept Park Hill during the late 1950s when the real estate industry – not just brokers and salesmen but bankers, appraisers, and insurance firms, black as well as white – began a brutal but money-making “Drive-out-the-whites and fill-in-the-blocks-with-blacks” push for a racial transition. This system had started in Chicago during World War I, and continued afterward, creating ever-expanding minority ghettoes in Milwaukee, Los Angeles, New York, and dozens of other cities nationwide, before arriving in Denver.

Park Hill white families suddenly became aware that something had changed in their neighborhood when they began to see more and more “For Sale” signs going up on homes around them, and more and more black home seekers – usually only blacks – driving up and down the streets looking at homes. What had changed? The real estate industry in Denver had quietly taken down an invisible wall around Park Hill that said, “No blacks allowed.” We who lived there had never been aware that there was such a wall, but it had been there, unbreakable, for 20 or 30 years. The “wall” consisted not of bricks and mortar, but simply of human will.

If a black family wanted to buy or rent a home in Park Hill, they would be politely steered to homes west of Colorado Blvd. and north of Colfax. If the black family insisted, the real estate man, if he were honest, would simply tell them, “I can’t get you a loan there; the banks aren’t lending to black folks in Park Hill.”

My late wife, Bea, and I experienced firsthand the breakdown of that wall one evening in 1959 or 60 when a man knocked on our front door, presented his real estate business card, and asked if we didn’t want to sell our house “while we could still get a decent price.”

We said we weren’t interested, but it didn’t matter. From then on, we and our neighbors were subjected to an endless barrage of leaflets on the front porch and phone calls from real estate salesmen. We were warned that, when blacks enter a neighborhood, home prices go down and most institutions of a city – police, trash haulers, street repair agencies, and above all the schools – tend to lower standards. So didn’t we want to get out while the getting was good? The real estate men assured us they had buyers waiting with money in hand. This, as the real estate men intended, started waves of worried over-the-back-fence whispers in the neighborhood.

But we finally received a different communication, one from Ed Lupberger, a layman at Montview Boulevard Presbyterian Church, inviting us to a meeting at Montview in May 1960 to discuss how to cope with this attack on neighborhood tranquility. That gathering led to the founding of the Park Hill Action Committee, Inc., an organization that at first consisted only of laymen and women from seven of the white churches in the area.

Park Hill Action, which in 1970 merged with Northeast Park Hill Civic Assn., the civic group north of Martin Luther King Blvd., under the new name of Greater Park Hill Community Inc., has had to continue fighting. To stay integrated, the group has had to struggle against not only low-achieving, segregated schools, but clueless city planners, public housing officials who tried to sneak more poor families into areas already impacted by HUD-assisted housing, and, for a while at least, black nationalists who claimed integration was passé.

And in Park Hill and neighboring communities, there is now a new threat: developers knocking down small homes – homes that minorities and lower and middle-income families can afford – and replacing them with multi-story mega-homes.

No one can say life in the inner city ever gets dull.

History supplied by the Greater Park Hill Community, Inc.

by Art Branscombe

Founding Member, GPHC

Frequently described as gentle and soft-spoken, Rachel Noel was tenacious in her pursuit of equality and opportunity in Denver city schools. Born in Hampton, Virginia, in 1918, Noel was educated at the Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) and Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, where she earned a master's degree in sociology. The daughter and granddaughter of lawyers, as a child Noel directly experienced the discrimination of a Jim Crow South. She had also been witness to the activism of her parents, including their efforts to register blacks to vote in Virginia.

Rachel Noel and her husband, Edmond, a surgeon, moved to Denver in 1949 to the Park Hill neighborhood. Active in community and educational affairs while also raising two children, events soon called Rachel Noel to public office and a central role in Denver's history. In 1962, Noel and others learned that plans for a proposed junior high school at 32nd Avenue and Colorado Boulevard would ensure an almost exclusively African American student body. Similarly, boundaries for Bartlett Elementary School ensured it would serve an almost exclusively white neighborhood. As Noel recalled almost 30 years later, "That was clearly a matter of race." Her response was political action. Black and white voters elected her to the Denver School Board in 1965. She was the first minority woman to serve on the School Board and served a single, six-year term.

After the 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Noel decided that the racial imbalance in Denver schools could no longer be tolerated. She introduced the "Noel Resolution" which called for the school district to provide equal educational opportunity for all children. This resolution eventually resulted in court-enforced desegregation of the Denver Public Schools. In 1974, the Supreme Court ordered busing to integrate the schools. Judge Matsch appointed Noel to the Community Education Council, a group to monitor Denver compliance and to report back to the judge. She worked with volunteers to accomplish this task. The busing program ended in 1985.

In 1969, Noel became an Assistant Professor at Metropolitan State College. She retired in 1980 as an Associate Professor of Sociology and the Chair of the Afro-American Studies Department. In 1976, Governor Lamm appointed Noel to the Board of Regents of the University of Colorado to finish the term of Jim R. Carrigan, who had been appointed to the Colorado Supreme Court. Noel ran for re-election in 1978, becoming the first minority to be elected to this position. She served on the Board until 1984.

In 1996, Noel was inducted into the Colorado Women's Hall of Fame. She was also a member of the Shorter Community African Methodist Episcopal Church and devoted volunteer hours to establishing a library.

Dr. Edmond Noel died in 1986. In 2007, Noel moved to Oakland, California, to live with her daughter. Rachel Noel died on February 4, 2008 in California.