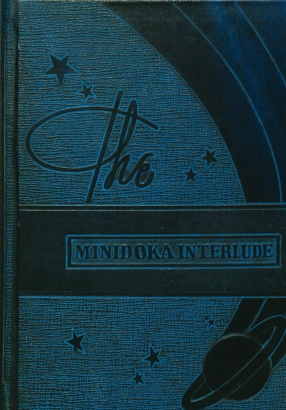

The Minidoka Relocation Center in southern Idaho is a scar on the reputation of the United States of America. During its era of operation, September 1942 to October 1945, its barbed wire fences held thousands of Americans of Japanese descent whose loyalty to America was challenged for no other reason than their race. Despite their circumstances, the inmates of Minidoka not only managed to create a semblance of "normal" life, but also documented their lives in a remarkable publication called The Minidoka Interlude.

Modeled after a traditional high school yearbook, the Minidoka Interlude is much more than a collection of headshots, though it contains photos of every camp resident. This publication documents nearly every aspect of inmate life through organization charts, descriptions of daily life and activities, timelines, and hundreds of photos of Minidoka.

One of the most moving portions of the Interlude is an introductory essay and dedication, authored by its editor Tom Takeuchi, which forcefully defends the honor and patriotism of the camp's inmates, saying: "We, as residents of the Minidoka Relocation Center at Hunt, Idaho take pleasure in dedicating this book to the 'America of Tomorrow' and reaffirm our faith in the principles and ideals of the founders of the United States." In the next 184 pages, Takeuchi and his Interlude partners paint a heartbreaking picture of average Americans attempting to scratch out a normal life on the dusty grounds of an Idaho prison camp far from the lush West Coast climates in which they'd lived before the War.

Life in Minidoka in many ways resembled life in the rest of World War II America. Children attended two elementary schools and a high school with more than 1,200 students. They tilled Victory Gardens and made the most of the limited goods and services that could be obtained during wartime. Of course, none of these people had made the decision to relocate to Idaho on their own. They were forced there as a result of FDR's infamous Executive Order 9066, which called for the relocation of Americans of Japanese ancestry from their homes on the West Coast to an archipelago of relocation camps across the West.

That the inmates of Minidoka were able to maintain any semblance of normal life, as well as a fierce loyalty to the United States, is a testament to the wrong-headed, and racist, nature of Executive Order 9066. It's worth noting that 844 men from Minidoka volunteered for military service in the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team and 73 of them made the ultimate sacrifice for their country. The families of soldiers killed in action were not allowed out of the camp to attend their funerals.

Camp inmates who didn't, or couldn't, volunteer for military service were put to work in Idaho's beet fields where 2,400 of them helped haul in the 1943 harvest. In an advertising section at the end of the book, an ad for the Amalgamated Sugar Co. thanks the "Japanese Workers" for their hard work in the fields. Other inmates helped run Minidoka’s administrative offices, stores, barbershops, and the other operations of daily life.

The Interlude at DPL

The Interlude is a very recent addition to the Western History Collection and it's one whose research value will only increase over the years. This title provides an incredible eyewitness view of camp life from inmates who clearly wanted to preserve a record of their sufferings and triumphs. For historical researchers, this kind of material is absolute gold as it includes names, dates, locations, and pictures that paint a very detailed picture of life at Minidoka. Of course, the Interlude is also a boon for the ancestors of camp residents who may not have any photographic records of their families during their incarcerations (owning a camera was usually forbidden in internment camps). Perhaps this is why he Interlude was the only publication of its kind produced in an American internment camp.

While there are multiple reprints of the Interlude available for purchase, original copies are few and far between, and the Western History Department is fortunate to have one. The incarceration of Americans of Japanese descent falls squarely in our collection scope. After all, the vast majority of internment camps were here in the West and almost all internees were Western Americans.

Housing this item also falls under our responsibility to collect the stories of those who are sometimes called, "forgotten people." While our collection is vast and multilayered, it has some serious gaps when it comes to telling the story of Western Americans who are not of European descent. Collecting items such as the Interlude helps us fill in those gaps and preserves a historical moment that is frequently overlooked.

Comments

Hello, I saw this story about

Hello, I saw this story about Japanese internment camps. I guess I expected to learn also about the internment camp in Colorado as well. I did a bit of research myself and found this site - https://amache.org/ It is a fully realized website with history, photos, and current news. I think this worth an addition to this story. I realize this story came from Brian Trembath. But Camp Amache is a fully realized and still memorialized site for persons of Japanese ancestry still living in Denver and Colorado. They also take a trek down to Granada, CO each May - since 1983. It was Granada Internment Camp first, but renamed Camp Amache - for this reason - "Granada Relocation Center’s unofficial name became “Amache,” named after a Cheyenne Indian chief’s daughter who married John Prowers (1839-1884), a prominent cattle rancher for whom the county is named." The Cheyenne Indian chief was killed in the Sand Hill Massacre (nearby). ALSO, and this is pretty exciting!

"The National Park Service is conducting a Special Resource Study to determine whether Amache meets the criteria to become a new national park. They need to hear from as many people as possible why it is important for Amache to become a National Park site." website: https://amache.org/

Dana Bennett, library patron, former docent

Add new comment