Early movements within black poetry had roots and examples in the black literary tradition, as well as roots from outside the black literary tradition. So what is black poetry? Donald B. Gibson, editor of Modern Black Poets: A Collection of Critical Essays (1973), suggests that "there are no terms or categories which will specifically distinguish the writing of black poets from that of others."

Black poetry refers to poems written by African Americans in the United States of America. It is a sub-section of African American literature filled with cadence, intentional repetition and alliteration. African American poetry predates the written word and is linked to a rich oral tradition. Black poetry draws its inspiration from musical traditions such as gospel, blues, jazz and rap. Black poems are inextricably linked to the experience of African Americans through their history in America, from slavery to segregation and the equal rights movement.

African American poets as early as the American Revolution wrote verse reflective of the time in which they lived. The earliest known black American poets: Jupiter Hammon (1711-1800), Lucy Terry (1730-1821) and Phillis Wheatley (1753_5-1784) constructed their poems on contemporary models. Lucy Terry wrote a brief narrative poem describing an Indian raid, a poem important not so much for its esthetics as for its historical importance. The poem, "Bar Fight," was written in 1746 or thereabouts and not published until 1855, is the first poem known to have been written by a black poet.

John Hammond, a Long Island slave, wrote poems primarily of a religious, moral character. He was conservative in his thinking and devoted to early Methodist piety; his poems were intended to be moral guides. His form was not considered original in style or content. Hammon, the first African American to publish a poem, "An Evening Thought" (1761), longed for salvation from this world, is based on a Methodist hymn, and in its construction echoes hundreds of other such similar work. Phillis Wheatley was drawn (same as Hammon) by the revolutionary fervor for liberty that culminated in the American Revolution. She wrote poems that reflected on her comfortable and privileged status as an educated slave. Her poems, as well as Hammon's verse, are about the issues of religious devotedness, patriotism and liberation, which did not address moral issues of slavery and universal equality.

Wheatley's first published poem appeared in 1770, and her first volume of verse, the first to be published by an African American writer, appeared in 1773 and titled Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, was written just two years before the American Revolution. Wheatley was taken to court soon after publishing her poems in order to prove a black person was capable of writing such refined poems. My research suggests and confirmed by literary scholars that Wheatley made little allusion to race in her poems, when she did, such references were few. Her own rebuke of slavery are preserved only in her personal letters. In fact, reading Wheatley's poems would not have revealed her racial identity.

On Imagination

Imagination! Who can sing thy force?

Or who describe the swiftness of thy course?

Soaring through air to find the bright abode,

Th' empyreal palace of the thund'ring God,

We on thy pinions can surpass the wind,

And leave the rolling universe behind;

From star to star the mental optics rove,

Measure the skies, and range the realms above,

There in one view we grasp the mighty whole,

Or with new worlds amaze th' unbounded soul.By Phillis Wheatley

Phillis Wheatly had a Denver connection for almost 50 years in the Five Points Neighborhood. The Phillis Wheatley Colored YWCA was founded in 1916 and became an official branch of the National YWCA in 1920. The Wheatley YWCA branch was located at 2460 Welton Street on the southeast corner of Welton just north of the now existing Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library at 2401 Welton Street. The Wheatley branch played an important role in the Five Points Neighborhood, because it provided a community 'common' place where African Americans could freely gather for meetings, social events, educational and training opportunities, and to swim. Laura M. Mauck in her book, Five Points Neighborhood of Denver (2001), states that "for almost 50 years, the branch operated a residence hall, youth camp, and employment bureau, and art and recreation classes." The Phillis Wheatley Colored YWCA branch closed in 1964. It was the last traditionally segregated African American YWCA in the United States to shutter its doors.

Other Nineteenth century black poets includes George Moses Horton (1797-1883?), Frances E.W. Harper (1825-1911), James Madison Bell (1826-1902), and James M. Whitfield (1823-1878). Their poetry was primarily political. They wrote against slavery or other wrongs perpetrated by society. Horton's first volume of poetry, Hope of Liberty (1829), was written with the expectation that his book would be successful enough that he would be able to purchase his freedom. Horton's book describes the evils of slavery. He became the first black poet to complain candidly about slavery. Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was the most widely known of this group because of her general involvement in the abolitionist and temperance movements. She was an abolitionist orator and poet, published her Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects in 1854. which was enthusiastically received by the public. This volume of verse included poems on the tragic circumstances of slavery and went through several editions by 1874, "The Slave Mother" and "The Slave Auction" were among the best of these poems. Harper wrote in conformist ways about similar subjects of interest and that were suitable for her time.

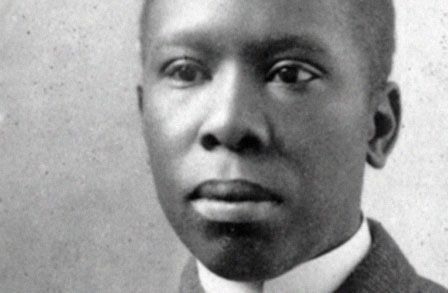

Paul Laurence Dunbar launched a new era in African American literature. He was one of the first black poets to gain national recognition. He was born on June 27, 1872, to freed slaves from Kentucky, Joshua and Matilda Murphy Dunbar. His parents separated shortly after his birth and he was raised by his mother. By the age of 14, Dunbar had published poems in the Dayton Herald. In 1893, Dunbar self-published a collection of poems called Oak and Ivy. He sold the book for a dollar to people riding his elevator to help pay the publishing costs. He received a formal education in high school, graduating in 1891. He was an excellent student and the only African American in his class. Unable to attend college because he lacked the finances and experiencing racial discrimination, he eventually took a job as an elevator operator.

1893 was important for Dunbar, because he had moved to Chicago, hoping to find work at the first World's Fair. There Dunbar befriended Frederick Douglass, who did two noteworthy things for him. He found Dunbar a job as a clerk, and also arranged for him to read a selection of his poems. Douglass said of Dunbar that he was "the most promising young colored man in America." In 1895, Dunbar's second book Majors and Minors (1895) drew favorable attention and the endorsement of literary critic William Dean Howells. Howells's introduction of Dunbar's third volume of poems, Lyrics of Lowly Life (1896) helped to elevate Dunbar's dialect poems to such an extent with white audiences that his poems written in standard English were often overlooked and unappreciated. It was Dunbar's dialect poems that made him famous.

Sympathy

I know what the caged birds feels, alas!

When the sun is bright on the upland slopes;

When the wind stirs soft through the springing grass,

And the river flows like a stream of glass;

When the first bird sings and the first bud opens,

And the faint perfume from its chalice steals -

I know what the caged bird feels!By Paul Laurence Dunbar (Standard English)

Jealous

Hyeah come Casesar Huggins,

Don't he think he's fine?

Look at dem new riggin's

Ain't he trying to shine?

Got a standin' collar

An' a stove-pipe hat,

I'll jes bet a dollar

Some one gin him dat.By Paul Laurence Dunbar (Dialect English)

Dunbar gained acceptance and popularity with white readers, because of the use of rustic or, as some described, countrified verse. Other poets followed the same style and perpetuated its technique. How did Dunbar feel about his dialect poetry? My research and supported by literary scholars suggests, that Dunbar felt his dialect poems were mostly inferior to his standard English poems and that they were not truly representative of his talent.

Although Dunbar's health began to deteriorate in 1898, he continued to write poems and books. His last novel, The Sport of the Gods, published in 1902, became one of his most impassioned attempts to protest the injustices of American society. As his health worsen he began to drink heavily. His declining health caused him to return to his mother's house in Dayton, Ohio, where he died of tuberculosis on February 9, 1906; he was 33 years old. He was mourned as the "Poet Laureate of the Negro Race." It should be noted that in the Twentieth century, scholars accused Dunbar of stereotyping and sugar-coating the harsh realities of plantation life, but today a more positive evaluation has emerged, and he has been re-appraised with more attention to the context of his time.

Essentially, my overview and drawn from the collection of essays edited by Gibson in Modern Black Poets - black poetry is defined as follows: Poetry written by black writers is racial - employing subjects, language, attitudes, and scenes from racial experience; or non-racial oriented toward experience that is common to the majority of people; or varying degrees of both of these at once. Black poets have written about racial protest, poems protesting against discrimination or other forms of racism. Black poets have written about black life and character, describing it or commenting on it in un-protesting ways and, finally, black poets have written poems from a completely non-racial perspective, poems indistinguishable from those written by non-black poets.

Sources:

Edited by Donald B. Gibson, Modern Black Poets: A Collection of Critical Essays, (New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc, 1973).

Laura M. Mauck, Images of America: Five Points Neighborhood of Denver, (South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2001).

William H. Robinson, Phillis Wheatley and Her Writings (New York: Garland, 1984).

The Poetry Foundation: Paul Laurence Dunbar, 1872-1906 at http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/paul-laurence-dunbar

Academy of American Poets: Paul Laurence Dunbar at http://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poet/paul-laurence-dunbar

Encyclopedia of World Biography: Paul Laurence Dunbar Biography at http://www.notablebiographies.com/De-Du/Dunbar-Paul-Laurence.html

Comments

As American as my integrated

As American as my integrated culture. I am an infusion of different cultures which have come together into mainstreem society. I am no pure race. In America, I have cultivated into a mixture of nationalities, ethnicities and cultures from around the world. Where am I now? I come from the American slave. I am a descendent of a mixture of nationalities. I am the African slave, but I too am American. The mixture of blood in me is very much American. The blood that runs through my veins is an Native American Choctaw Indian princess. I am a proud legacy of an African worrior tribe. A proud decendent of an African chief. My great grandmother was native American Indian, Irish and German. I am Creole Indian. My great grandmother was Chinese and black Indian. I am Itilian, Hawiian and African from the Nigeria, Senagal, Congo and from regions of South Africa. I have learned to place my predjudice beside me. Being a mixture of things, I have learned to embrace different cultures as a challenge to integrate with society. We all have different backgrounds, cultural traits and mannerisms that make us unique characters. It is from our diverse personalities that makes American a model society. America built this nation on multiple backgrounds of diverse difference that define who we are. I am African American and my body is made to be Native American Indian. My body is developed charteristics of my great grandmother. The native American Indian has developed a small chest. My bra size is 36 B. I developed that character trait from the Indian blood that runs through my veins. The native American Indian is said to be short. My great grandmother was 4'8 inches and I am 5'0 inches tall. It is a Native American Indian princess trait to spill blood from the uterus. I am a carrier of the Native American Indian princess to have a menstral every three weeks and spill red blood from my uterus. This characteristic is different from the African menstral period. I can only have sex the Native American Indian way because my cervix is disigned differently than an African American cervix. The color of my skin is Choctaw Indian skin pigment. Some people ignorance have mistaken me for having African attributes. They say I look African so I must be it. I know differently. I can only be what I am. I am an American. I am the result of the "melting pot" and I can not deny my heritage. I will not accept being profiled as African but as an American proud to be who I am. The melting pot for me has become defined as an American expression of what it means to be an American.

Speaking out, a relfection of expression

Life is difficult without words

The presence of a voice

Carries on as a reminder

Of emerging thoughts

Thought remains unpinned

From aggression

I am the voice of

Advocating hope

From restriction

I am the voice of

Promoting peace

My voice demands justice

To be respected

My voice demands justice

To want dignity

I act in

Defiance to unkind indifference

I act in

Response to unkempt change

My voice is a criminal of self-thought

Darkness is the impedemy of silence

very great....gretings from

very great....gretings from gremany....i have no eyebrowns btw

* greetings.....*germany.....

* greetings.....*germany.....*eyebrows

The photographs posted online

The photographs posted online with some of Jupiter Hammon’s biographies cannot be pictures of Hammon himself – we know that he died before 1806, and photography wasn’t even invented until the 1826.

Reading this to create a

Reading this to create a scaffold for my students. I was born and raised in Denver CO and it's interesting to know about Phillis Wheatley's legacy there

Add new comment