The patent medicine era certainly had no shortage of outrageous and preposterous claims, nor did it have a dearth of “remedies” for any affliction, real or imagined. Of all the nostrums, tonics, unguents and balms on offer, perhaps none were as audacious or absurd as those invented by self-proclaimed “chemist” (John) Philip Schuch Jr.

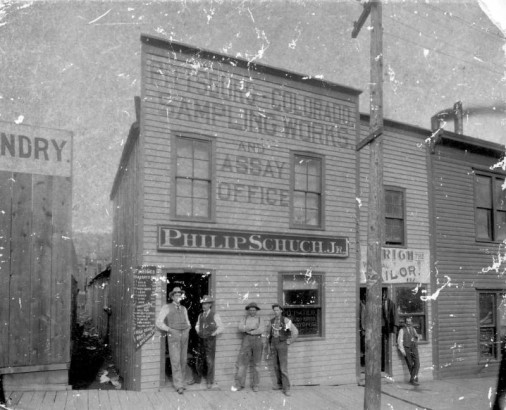

Schuch grew up in Del Norte, Colorado, and as young man relocated to Creede, where he amassed a fair amount of money selling mining property and town lots. He later moved to Cripple Creek where he became a prominent assayer… until February 24, 1902, when his was one of eight assay offices destroyed by dynamite (for reasons not entirely clear, but likely having to do with assayers skimming a bit of high-quality ore on every transaction).

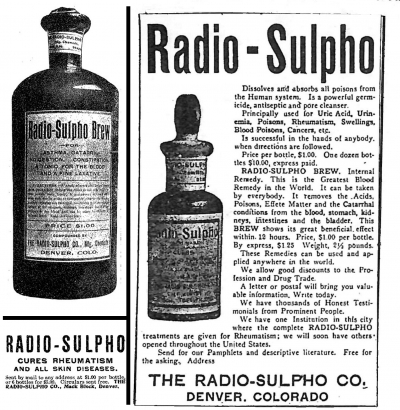

Following this setback, Schuch tried in vain to get a few new mining-related businesses off the ground, but all of them floundered. He then traveled to Europe, returning to Colorado several years later by way of South America. On his return, he declared that during his travels he had extensively studied the “healing waters” of the bohemian town of Karlovy Vary (Carlsbad) in what is now the Czech Republic. Now billing himself as a chemist and cancer specialist, he set up shop in the Mack Block at 16th and California in downtown Denver and began heavily marketing Radio-Sulpho, a treatment consisting of a wretchedly stinky external wash, and a brew to be taken internally.

The tonics were billed as cures for rheumatism, swellings, blood poisons, cancer, and pretty much any other ailment. The pair could be acquired for the low, low price of only $25 (or more) per month, and if you had the means, Philip Schuch Jr. would treat you in person for just $100 per day (or portion thereof) plus travel expenses. The caveat, according to a sales brochure, was that Mr. Schuch would “treat personally the white race only” (which could have brought some measure of solace to non-whites, I suppose).

His promotional literature also stated that “cancer of the womb and breast are the simplest, easiest and quickest cures made,” and it’s with cancer treatments that Mr. Schuch rises to the top of the absurdity scale. While the Radio-Sulpho brew and wash were deemed adequate for treating rheumatism and the like, cancer required a third step. Once the brew had been ingested, and the skin over the area plagued by cancer had been thoroughly “cleansed” with the wash, Schuch advocated applying a poultice of fresh, pulped limburger cheese moistened with glycerin (repeat every twelve hours).

To paraphrase one editorial, apparently Mr. Schuch believed that cancer had a keen sense of smell. For a time, the company was quite profitable, but that changed abruptly in 1906 with the passage of the Pure Food and Drug act. The company’s claims were quickly brought to the attention of the Colorado State Board of Health, and state chemist Dr. E. C. Hill analyzed their products. He determined that the “wash” was an alkaline solution rich in sulphur dioxide (the substance which gives rotten eggs and Yellowstone Park such noteworthy aromas). The “brew” was merely a diluted mix of Epsom salts, with some bitter vegetable juice mixed in to mask the flavor. (Presumably, the limburger cheese was found to be just that.)

Shortly after his conviction, Philip Schuch Jr. was found dead in his room at the Shirley Hotel. While initially thought to be heart failure, Schuch was in possession of a note accusing Dr. W. C. Wright, one of Radio-Sulpho’s investors, of poisoning Schuch’s whiskey. An autopsy indeed found arsenic crystals in his intestines and liver, and Wright and a cancer patient, Leo Neujahr, were charged with Schuch’s murder.

If this kind of tale strikes your fancy, I highly recommend swinging by WHG and perusing a book called Nostrums and Quackery, which first drew my attention to this tale. Also, be sure to like our Facebook page to stay up to date on all things Western History and Genealogy related.

Add new comment