At their core, books are all about content.

That is to say, the text of classic book, like the Canterbury Tales, is going to be the same whether you're reading the first edition in a special collections reading room or sitting by the pool reading it on your iPad.

While that statement may be true for most of us, that's not how hardcore bibliophiles (book lovers) see the world, and it's most certainly not how William Morris, the founder of the Kelmscott Press, saw the world.

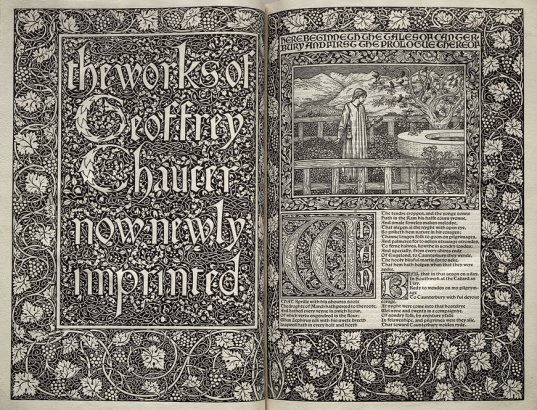

In the years between 1890-1896, Morris operated the Kelmscott Press on a second-hand printing press. During that time he produced 52 titles, in 66 volumes, of what are considered some of the finest examples of the printed word ever produced. (Approximately 48 of these titles are housed at Denver Public Library as part of our Douglas Collection of Fine Printing.)

So what is it that makes a Kelmscott edition of Chaucer or Beowulf so special? The short answer is, everything.

Morris obsessed over every detail of creations, from the custom typefaces he designed himself to the proprietary black ink he imported from Hanover, Germany, to the handmade paper he printed it all on. No detail was too small for Morris' learned gaze.

But Morris didn't just want his books to look good, he wanted them to be truly readable. Tremendous thought was put into the spacing between letters and other minutiae that readers probably wouldn't consciously notice, but would definitely experience.

Morris was a textile designer by trade and was generally disappointed with the quality of goods, including books, that were being produced in Victorian/Industrial Revolution-era England. In his textile business, he strived to produce quality products that mirrored the work done by master craftsmen.

His ethos would probably be called DIY today and was very much in line with the English Arts and Crafts movement which had really picked up steam during this era.

The Kelmscott Emerges

No matter what you call it, and despite its status as an actual business with actual employees, the Kelmscott Press was very much a labor of love. Morris, and his partner in art, Edward Burne-Jones, spent their Sundays meticulously producing the engravings that would make their works so special. (Though, in fairness, it should be said the two were working feverishly to complete the Chaucer book before Morris' health failed him completely.)

In fact, Kelmscott the press was so influenced by Morris the man that it shut down completely after his death in 1896. Though Morris had hoped the Kelmscott could continue without him, his employees knew that there was too much of Morris in the press to continue on without him.

Kelmscott at DPL

DPL houses its Kelmscott imprints as part of the Douglas Collection of Fine Printing, which showcases superior examples of print, typography and book binding. The collection contains an incredible variety of items ranging from Babylonian clay tablets to rare editions of classic books, and a large collection of unique, handmade books. The only thing these items have in common, besides being books, is that they're all absolutely gorgeous.

The City of Denver is extremely fortunate to have the items in the Douglas Collection of Fine Printing as a resource for both scholars and citizens alike, and the Kelmscott imprints are the crown jewels of this amazing collection.

(Because of their fragile nature, the items in the Douglas Fine Printing Collection can only be viewed by appointment only. For more information email: history@denverlibrary.org).

Highlights of this collection include:

- The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer: Now Newly Imprinted (Kelmscott, 1896)

- A Collection of Book Bindings (British Museum Publications Ltd., 1979)

- Babylonian Clay Tablets

- Extinct Extant (Alicia Bailey, 2015)

Comments

Hey Brian ~ Great blog - this

Hey Brian ~ Great blog - this is great stuff to bring out. You might like this blog I did a while back along similar lines:

https://history.denverlibrary.org/news/book-lovers-tour

Add new comment