Next year, the Wilderness Act—the law that created the means to protect nearly 110 million acres of wilderness area in the United States—turns 50. Tragically, the author of the Wilderness Bill, Howard Zahniser (1906-1964), did not live to see President Lyndon B. Johnson sign the bill into law on September 3, 1964. Zahniser passed away from heart failure just four months before the historic bill was passed.

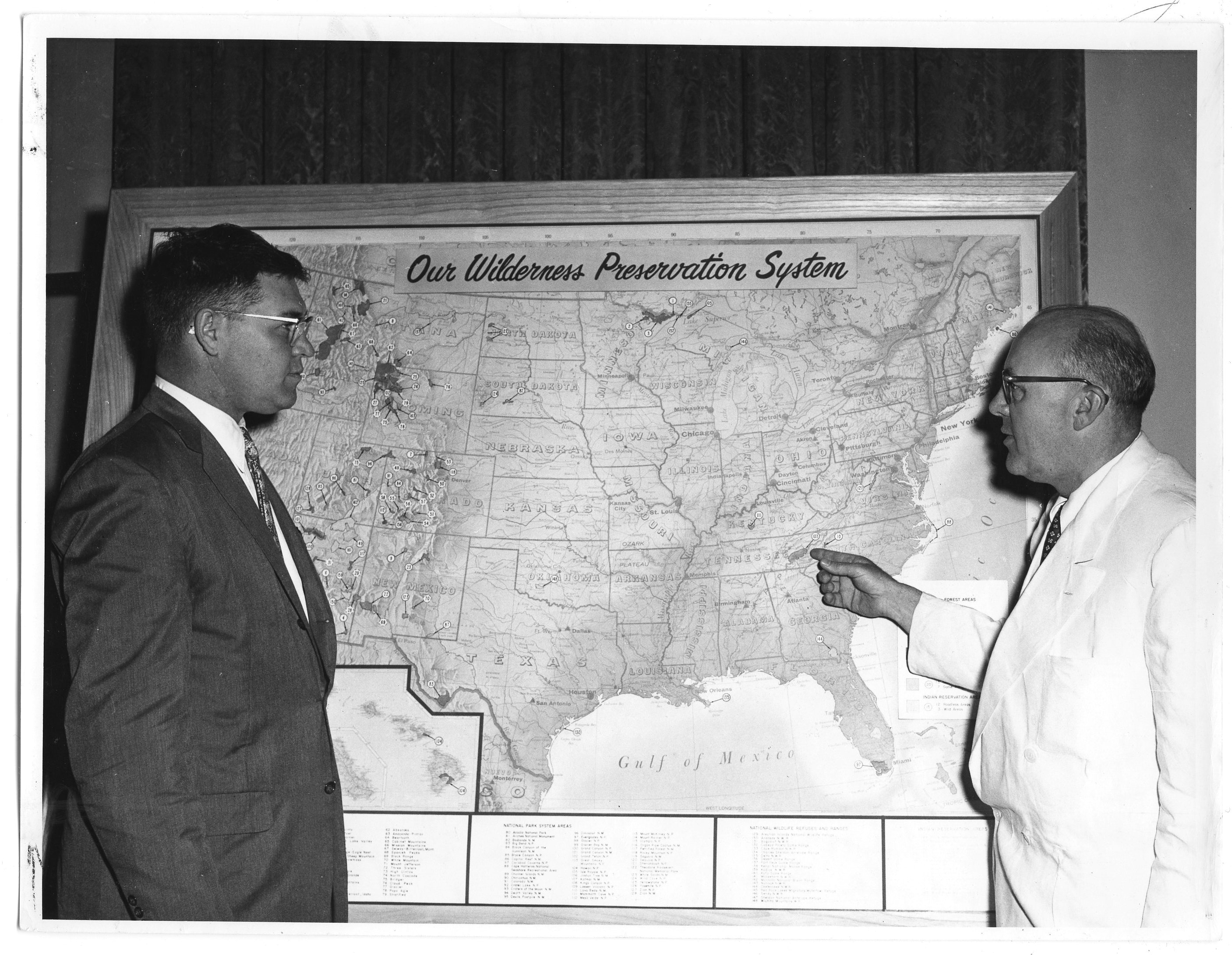

The unlikely journey Zahniser took from public servant to conservation activist is documented in the Howard Zahniser Papers (CONS 238), now available for research in DPL’s Western History and Genealogy Department. This collection provides a fascinating record of Zahniser’s professional and personal life, illustrated through journals, notes, article drafts, speech transcripts, congressional statements, correspondence, poems, photographs, and audio recordings. These materials reveal not only the people, places, and literature that influenced Zahniser, but also the way in which Zahniser’s concern for wilderness areas increased over time, reaching a fever pitch when he began his first draft of the Wilderness Bill in 1956.

The son of a Free Methodist minister who moved his family frequently, Zahniser spent his teenage years near Pennsylvania’s Allegheny National Forest, where he cultivated a lifelong interest in nature and literature. After graduating from Greenville College, Zahniser relocated to Washington, D.C. where he held editing and writing positions with the U.S. Bureau of Biological Survey and the Bureau of Plant Industry, Soils, and Agricultural Engineering. From 1935 through 1959, he wrote the columns “Indoors and Out” and “Nature in Print” for the American Nature Association’s Nature Magazine.

The direction of Zahniser’s career changed when he accepted a full-time position co-leading The Wilderness Society in 1945 and worked alongside notable conservationists Olaus Murie, Benton MacKaye, Aldo Leopold, Robert Marshall, and Harvey Broome. Zahniser looked to grow the society and its influence, and was successful in significantly increasing membership. Beginning in the 1950s, Zahniser became progressively more concerned over the growing number of wilderness areas threatened by dam building, logging, mining, farming, and tourism and transitioned into an activist role.

Zahniser left behind contributions that extend far beyond the number of acres his life’s work now protects. Using his media savvy and talent for crafting messages, Zahniser brought wilderness conservation to a mainstream American audience. The Denver Public Library’s Western History and Genealogy Department is proud to preserve the papers of Howard Zahniser—a conservation pioneer.

Add new comment