Civil Records from the 1850s Forward

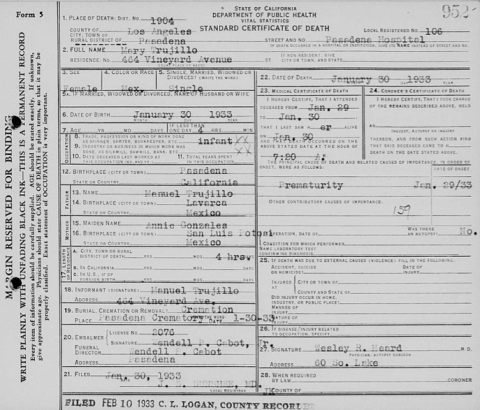

With some rare exceptions, civil records documenting births, marriages, and deaths generally do not exist before the second half of the 19th century, either in Spain, Latin America, or the United States. Some countries, such as Bolivia, did not start a civil registry until the 1940s. When local, state, and federal governments began to record those events, it was not uniform or widespread. Some families may not have had these events recorded and in the absence of civil records, especially in the Spanish colonial period, church and military records are the only source for documenting ancestors.

Census and Military Records

Civil, military, and church authorities took counts of their populations, which you will find listed as “censo” or “padrón” in catalogs, libraries, and archives. Censuses were taken during the colonial period through the present day. Depending on the place and time, they may be as simple as a priest listing all the parishioners as family units in his jurisdiction or the mayor listing men, their occupations and ages, and the number of people in their households. Some census records will be detailed and parallel modern censuses by including occupations, marital status, caste or ethnicity, age, property, servants, and slaves. Some of the most complete national censuses available online are the 1895 census of Argentina and the 1930 census of Mexico.

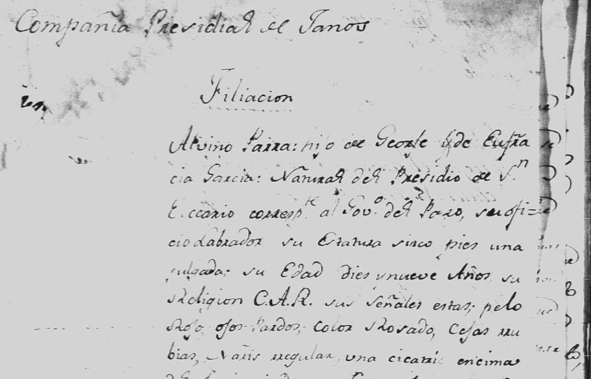

Military census records might only contain name and rank, but sometimes include birthplace, age, and other information such as height, skin color, eyes, and hair. They are useful to fill in the gaps of missing church and civil records.

Spelling Variations in the U.S. Records

It is important to note that records in the U.S. may also have different spellings or missing accent marks, in particular when the person writing the name down did not read or write Spanish. For example, “Eduardo” can become “Edwardo,” “Federico” can become “Frederico,” and “María” can become “Mary.” For many different reasons, people may have Anglicized their names on their own, so “Carlos” became “Charles” and “Inés” became “Agnes.”

In addition, English speakers tend to drop or omit diacritics (accents and tildes) on names, so “Núñez” becomes “Nunez.” However, this is changing as more people value the role diacritics play in written Spanish and how writing names correctly is a critical part of equity, diversity, and inclusion.

This series is designed to help customers deepen their research while learning about Hispanic cultural traditions and customs they may encounter in their family history and genealogy records.

Comments

Well written; short and sweet

Well written; short and sweet.

Add new comment