In 1876, Fred Harvey had an idea that, at the time, seemed pretty radical. He wanted rail companies to serve good, hot, edible food to their passengers at train depots across the west.

Harvey's idea was definitely out of the mainstream because, at the time, railroad food consisted of what the authors of Visions & Visionaries, The Art & Artists of the Santa Fe Railroad describe as, "rancid bacon, canned beans, or three kinds of eggs - eggs from the East aged and preserved in lime, ranch eggs from local farms and yard eggs laid near the depot.” These delicious meals also included soda biscuits, called sinkers, as well as your choice of cold tea or bitter coffee.

To make things even worse, rail workers had a little scheme going wherein they would serve up meals right at the tail end of a stopover so that travelers would abandon their relatively uneaten meals. Those meals would then be served again, allowing for double dip profits.

In short, the railways of the Trans-Mississippi West were in desperate need of a makeover, and Mr. Harvey was just the man for the job.

Meet Fred Harvey

Harvey was an immigrant who came to New York from London in the classic manner of the era. That is to say he was penniless and not particularly familiar with the US.

After a series of low-level jobs at restaurants in New York and New Orleans, and a failed try at running a restaurant of his own in St. Louis, Harvey wound up working for the Atchison, Santa Fe, Topeka Railroad in Leavenworth, Kansas.

That’s where he approached a Santa Fe rail executive who was open to his idea.

Harvey was given the green light to open a new kind of railroad restaurant and the results were very successful. In fact, Harvey’s influence on the Atchison, Topeka, Santa Fe Railroad, and the public perception of the railroad, were nothing short of incredible.

In the 114 years since his death, Harvey has been credited as the “Father of Western Hospitality” and the “Civilizer of the American Southwest.” His Harvey Houses and Harvey Girls became a real attraction for Atchison, Topeka, Santa Fe Railroad travelers and helped build the railroad’s nationwide reputation.

Harvey was more than familiar with rail travel thanks to his position with the railroad, as well as his multiple other freelance jobs (including advertising salesman for a local newspaper), and he logged many hours on trains. That was more than enough to convince him of the need for better quality hospitality for travelers.

He was also something of a ringer. Harvey and a partner had already test-driven his idea with a chain of three dining rooms along the Kansas Pacific Railroad, including one in Hugo, Colorado. While these restaurants were met with some success, the railroad itself wasn’t doing all that well.

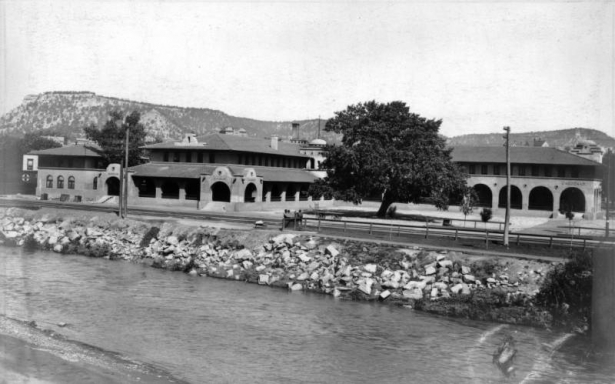

With an eye on a railroad, that was closer to home, Harvey launched his first Harvey House at the Topeka Station.

The First Harvey House

The Topeka Station lunchroom and hotel operated on a whole other level from what rail travelers were used to. Harvey’s lunchroom included white linen, china and good food prepared by a real chef.

After thoroughly cleaning the Topeka facilities, Harvey launched what would become his masterpiece. For a mere $.35 (about $7.00 in today’s currency) travelers could enjoy steak and eggs, hash browns, six pancakes, coffee and pie for dessert.

Not surprisingly, Harvey’s new dining room was a big hit and stayed that way for many years to come.

By 1915, according to Hotel, Motor Hotel Monthly, the Harvey House chain was annually serving up:

- 5 million meals

- $750,000 worth of meat and poultry

- $175,000 worth of ham

- $60,000 worth of bacon

- 500,000 pounds of coffee and 15,000 pounds of tea

- 4,500,000 pounds of flour

- 5,000,000 pounds of potatoes

- 1,500,000 pounds of sugar

Harvey House also required a tremendous amount of cleaning supplies to maintain their standards and so it was that they spent $30,000 on non-soap cleaning supplies such as silver polish.

There was, however, one problem. The men who worked the railroad dining rooms - the same ones who served up those "delicious" railroad meals before Harvey entered the picture - were hardly a good fit for Harvey’s vision.

Enter the Harvey Girl

Harvey was an expert in the art of the surprise visit and frequently showed up unannounced at his far-flung businesses. During one of these inspections, he found that the staff members (all male) were bruised and battered from a brawl the previous night.

Seeing his employees in their disheveled state gave Harvey an idea. He decided that his rough and tumble railroad men would be replaced with women. Specifically, attractive women who would become known as "Harvey Girls."

These young ladies, for better or worse, were something of a forerunner to the ladies who work in restaurants such as Hooters and the Tilted Kilt. At the same time, they elevated the reputation of the Santa Fe Railroad and helped create the railroad’s unique brand.

Harvey, not Hooters

When viewing the Harvey Girls through a modern eye, it's easy to mistake them for something akin to Hooters Girls, but that's not really an accurate description at all. Though Harvey Girls were selected for their looks, they were also expected to be both intelligent and of a relatively solid moral character.

Harvey Girls lived in dorms and were expected to follow a large set of rules, which included a 10 p.m. curfew. Their attire was modest and a far cry from the half shirts and miniskirts that mark today's breastaurants.

Not surprisingly, Harvey Girls were quite popular in the small towns where they worked, especially those towns where women were few and far between. In fact, so many Harvey Girls married local men that any girl who worked for more than six months was considered something of an old-timer.

Harvey Houses Peter Out

Though Harvey's rail depot restaurants were a big hit with rail travelers, they took a serious hit at the dawn of the automobile age and the beginning of the Great Depression. This era saw a steady decline in Harvey House business as travelers sought to blaze their own trails, in their own vehicles.

Despite a brief surge in business during World War II, as hundreds of thousands of soldiers headed west for training, the Harvey House rapidly turned into a relic from a bygone era. By 1963, Harvey's business was shuttered, but the legacy of the man who civilized the west lives on.

Want to learn more about Harvey, the Santa Fe Railroad and its contribution to the art world? Join Denver Public Library Special Collections Librarian Brian Trembath and American Museum of Western Art Museum Educator Kristin Fong on June 10 for a talk on, "Southwest Tourism by Rail." The event starts at 3 p.m. and reservations are required.

Comments

Yes, both Harvey Girls and

Yes, both Harvey Girls and Hooter's Girls are hired based on their appearance but you're clearly implying that Hooter's Girls are neither intelligent nor "...of a relatively solid moral character" and that is inaccurate and unfairly judgmental. The language used in this article perpetuates misogynist attitudes (i.e. belittling, sexual discrimination and objectification of women) and, frankly, seems uncharacteristic for a public library. Is it possible to share historical facts in a way that inspires a better future for everyone?

Hi Hooter's Girl - Thanks for

Hi Hooter's Girl - Thanks for your comments on this blog post. I do apologize if this content came across as sexist or misogynistic, that was definitely not the intent.

The point I was trying to make was that while Harvey Girls were selected on their looks, they were also held to rigid standards that no restaurant employee today would be expected to adhere to (such as the 10 p.m. curfew). It was in no way meant to disparage the moral character of women as whole and, specifically, those who work at Hooters.

That said, I will definitely keep your concerns in mind for future blogs. Thanks again for both reading and commenting on our material.

I didn't interpret your

I didn't interpret your article to be sexist or misogynistic at all. You were simply comparing and contrasting eras. Very good article!

Add new comment