Denver’s Pioneer Monument, a sculpture-adorned fountain at the intersection of Broadway and Colfax, was erected in 1911 as a display of Denver’s place in the intensely complex migration branded as “Manifest Destiny.” This symbol, born of aspirational memory-making and established half a century after the city it hailed, immediately became a source of controversy and concern about public art, pioneers, and the nature of the American West.

The American Indian Movement of Colorado has pushed for years to remove the statue of Kit Carson at the top of the monument, describing his continued memorial as “erasing ‘the existence and histories of indigenous peoples and nations.’” Carson’s most controversial (though certainly not his only controversial) actions took place during his military years. He implemented a scorched earth policy against the Navajo people to force them to submit to the reservation system, a campaign during which hundreds to thousands of Navajo men, women, and children perished. When Carson’s statue was removed (temporarily) in June 2020, as the city and nation reckoned with history’s darker truths, many saw it as a win, however small.

Yet Carson’s monumental figure already represents a reworked vision of this Denver fountain. The initial design of the statue featured a mounted Native American man in a warbonnet where Kit Carson eventually came to stand. Public monuments say as much or more about the people erecting them than they do about the people they depict. So what does this one say? What would the original design of the Native American warrior have said? And how do we reconcile these historic visions into the 21st century?

Initial Designs

In 1905, members of Denver’s Real Estate Exchange raised funds toward building a monument honoring the state’s pioneers. With the backing of Mayor Robert Speer, they secured a triangular space between Colfax, Broadway, and 15th Street, near the eleven-year-old State Capitol building. Funding for the monument, which would ultimately come to about $75,000, came from subscribers (a veritable who’s who of Denver society) as well as from the city and state.

Denver’s Pioneer Monument was part of a larger movement, down to its Beaux-Arts styling and the selection of famous artist Frederick MacMonnies as designer. In her research on Pioneer Mother Monuments (a subset into which Denver’s Pioneer Monument’s “Mother Group” falls), Cynthia Culver Prescott lists seven prior monuments honoring pioneers in a similar design, including in San Francisco, Salt Lake City, and Portland, Oregon.

When MacMonnies submitted his design, the plans were unanimously accepted by a formal vote of 50 subscribers. They then passed to the park commission and the Real Estate Exchange for ratification, as the public got their first look at the design in the Rocky Mountain News. By May 16, 1907, the contract was finalized, but the war over the monument had just begun.

Uproar

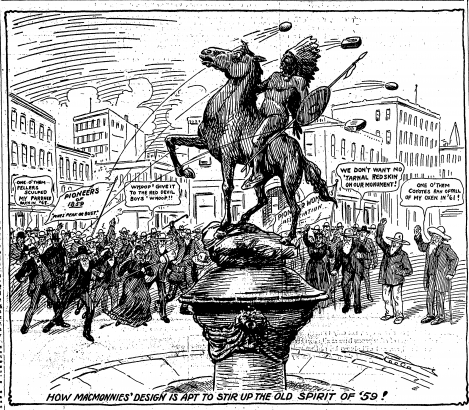

Fanned by the era’s press, Colorado’s pioneers reacted with passion and enthusiasm that impressed even MacMonnies. Despite the initial description of the monument as “a gradual transition from civilization to savage life - the fountain monument rising from the city of Denver,” groups such as the Society of Colorado Pioneers decried the plans for an “Indian chief” at the monument’s highest point. They went so far as to threaten an injunction protecting the name “pioneer” on the monument and send an emissary to argue their case directly to the artist in Paris. The Rocky Mountain News of June 2, 1907, suggested, “It is possible, but improbable, that they may yet figure out some suitable alteration that will placate the pioneers.”

Apparently in response to the furor, MacMonnies wrote a letter to John S. Flower, a subscriber to the pioneer monument fund. His explanations and justifications were published widely in the June 2 issue of the Rocky Mountain News.

This letter elaborated on MacMonnies’s vision for the fountain and what it might mean, and leaves little space for arguing that the intended Native American at the top would have been a crowning achievement. The native man was intended as a symbol of a “redoubtable and vanished foe,” illustrating the pioneers’ victory. He would be smaller in physical scale, a “finial, not a crowning figure,” and poetically would be “mounting and disappearing forever.” Further, he argued,

“I believe the people of Colorado able to admit a point and generously recognize the historic place upon the pioneer fountain monument of the greatest enemy of civilization known to history, the redskin, inseparable from the noble achievements of the pioneers who made Colorado.”

Clearly, MacMonnies felt no compulsion to defend Native Americans, regardless of their placement in his designs. Interestingly, research into his non-public discourse suggests that MacMonnies felt particularly excited about the artistic opportunity to depict a heroic Native American offering peace. This “progressive” vision was tied to historian Frederick Jackson Turner’s 1893 declaration that the frontier was closed, and to the idea of the “vanishing race” so eloquently manufactured in the photographs of Edward S. Curtis and Joseph K. Dixon.

Legacy of Controversy

If MacMonnies had hopes that his “explaining away” would appease the Colorado pioneers, his assumption proved foolish. Rather, the letter whipped up even more frenzy. On June 16, the Rocky Mountain News featured several written replies that made emotional pleas against any representation of a living native (peaceful or not). In a vitriolic argument that recalls the Sand Creek Massacre, “R.N. Irwin” wrote,

“(A dead Indian below would be all right, but one rampant is an eyesore.) I wouldn’t want any friends of mine to see such a disgusting monument. The weak explanation of the artist that this was a ‘peaceful’ Indian and that he was only a ‘finial’ anyway (though set on top of all) was too much like these ‘good’ Indians, with a written certificate of character, we used to meet on the plains forty-five years ago.”

The arguments continued to rage through the summer of 1907, until MacMonnies returned to Denver in August. Bowing to pressure, he replaced his “objectionable” "Indian chief" with the statue of Kit Carson that has become so controversial in the ensuing century. For the time being, though, complaints died down and MacMonnies was free to return to Paris and work on his statues in peace.

The fury over the initial Pioneer Monument designs reinforce the fact that our current debates about history and how our monuments define us are nothing new. Similar to many of the Confederate statues currently under review across the country, the story told by our Pioneer Monument is a complex one, with racism, memory, and memory-making deeply intertwined. As we rethink how we memorialize and contextualize our history, there are so many monuments that will demand re-understanding.

Comments

Very interesting article,

Very interesting article, thanks. I would never have thought there was a proposal for a statue with a Native American warrior, at the time it appears to have been pretty radical. This also shows the role that past politics has played in the establishment of supposedly "timeless" memorials. Good job.

Thanks for reading and

Thanks for reading and commenting, Jude. I love taking the long view of history to get perspective on today's issues.

interesting article, thank

interesting article, thank you.

I am working on my family history and have learned to watch my word choice so that I am honoring the native people who lived here before us. My ancestors came to Colorado in a covered wagon in the 1860s and homesteaded. I discovered where their land was and was excited to then learn about thir one-room school house, and what they farmed, and where exactly they might have built their log home etc. Though this family story is fun to discover and to share with my relatives, I've chosen to say things like, "we were the first Europeans to live in the area". And though there is nothing to indicate my ancestors were directly involved in forcing out native people, still - I have learned to at least give a nod to their place in my family's story. It's important, as you state, "to contextualize our story". Thank you for pointing that out.

Thanks for reading and

Thanks for reading and sharing, Mary. Context is so key. Glad to hear that you are implementing this as you approach your own family history.

"Rethinking" OK, but "Re

"Rethinking" OK, but "Re-understanding" is not a word in any dictionary that I find including the OED. It connotes accepting the popular or politically correct position without logic or examination.

Re-understanding may not yet

Re-understanding may not yet be in the OED, but it has been used in published texts elsewhere. We see it as the obvious result of rethinking, regardless of politics: a new or renewed understanding. Thank you for reading!

Even as a 4th generation

Even as a 4th generation Denverite, I did not know that the the figure atop the monument was Kit Carson. I assumed it was a generic pioneer marking the end of the Smokey Hill trail and pointing the way to the gold- and silver-rich mountains to the west. Carson was an extraordinary figure but, knowing his part in the removal of Navajos from their reservation to Bosque Redondo, I understand Native American's resentment of him.

Thanks for reading, Bill!

Thanks for reading, Bill! Western History (and history generally) is full of complex figures who did both good and ill to and for those around them. Kit Carson is just a very obvious example. His story is nuanced and complex, and compassion is understanding the view of those who were and are hurt by his actions.

It's good that we all "give a

It's good that we all "give a nod" to the Native tribes that once roamed and relied on the land of our ancestors by acknowledging them through our word choices, and for our library and museum to state that they are built on top of land that was once inhabited by Native Americans. But I think we must remember that the tribes that still exist suffer in very real ways today because of "manifest destiny" and all it's consequences. Acknowledging that some tribes once lived here, although a start, does nothing to alleviate their suffering. What are some real and tangible ways we can help repair some of the painful results of our hegemony? I include myself in the "we" and "our".

Great questions, BJ! Like all

Great questions, BJ! Like all cases of historical and systemic racism, helping Native American communities is not just about learning that history. There are tangible ways to help communities today. Listen by reading indigenous authors, support monetarily by finding organizations that donate specifically to Native causes, purchase directly from indigenous artists and manufacturers. These are just a few ways to help people now. Thanks for reading and for your interest.

Add new comment