One of the worst floods in Colorado history began on June 3, 1921, as dense rain clouds gathered in the low mountain ranges and the Dry Creek area west of the city. During the afternoon the clouds began to spill their massive amounts of rain and pushed closer to the city of Pueblo, Colorado, a city dominated by the steel mills of the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company and an important railroad center. Pueblo lies at the confluence of the Arkansas River and Fountain Creek. Most of the business district and the railway yards were in the lower parts of the city, near the rivers. There was a prior flood in 1894, and afterwards, levees were heightened and strengthened, bridges raised, and the channel widened to accommodate a potentially greater runoff. Several large and heavily traveled railroad and vehicular bridges crossed the Arkansas River, and by approximately 7 pm, the river rose eight feet in the narrow river channel running through the lower part of the city.

At 6 pm, the flood warning began to sound and reached all parts of the city. However, a holiday spirit permeated the populous as hundreds of men, women and children rushed to the flood bank, bridges and other areas to get a better look at the flood, as debris, trees and dead animals swept by. The muddy water started to reach the tops of the levees, but the crowd stayed on, enchanted by the power of the flood. Not until later in the evening, around 8 pm, did Puebloans begin to take the flood seriously. Police began driving onlookers from bridges, as trees hurtling with with the speed of express trains hitting railings and bridges, reports of water cresting levees and water coming up out of manholes.

Two passenger trains were waiting in the depot yards along with their remaining passengers. The decision was made to move the trains across a bridge to a safer area across the Arkansas. However, as the flood became worse, and the river started to pound the bridge flooring, the plan was abandoned, and the trains were stalled side by side near the river.

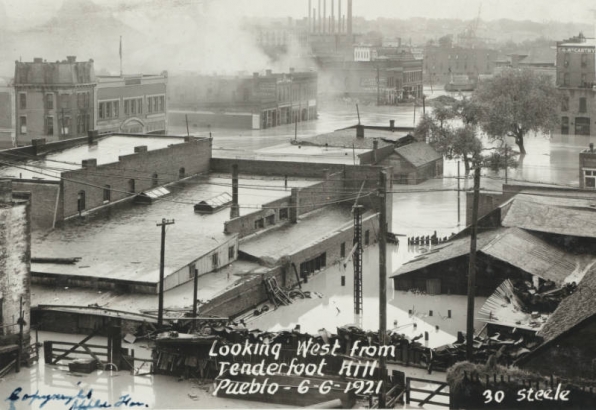

At 8:45 pm, the Arkansas River overflowed its channel. The crowds watching the flood on the Union Avenue viaduct saw the dark and muddy water racing through the depot yards. Their excitement turned to gasps as suddenly all of the lights in the city went out all at once. A loud crash of thunder and a fresh deluge of rain finally reached their full intensity over the dark city of Pueblo. Part of the city lower than the tops of the levees was now underwater. Larger and larger objects and pieces of wreckage now came down the river and channel. Houses and buildings ripped from their foundations, only illuminated by flashes of lightning and crashing thunder. Fires started breaking out, desperate people took refuge on roofs and tops of buildings. Many had delayed their departure from the downtown area's danger, only to be caught by the flood and dashed to death. To make matters worse, burning piles of timber from a lumber yard drifted through the streets, lodging against wood buildings and setting them afire. It was impossible to fight the fires, as the buildings were surrounded by water and the city's water system also went down.

In the railroad yards, full and empty cars were tossed aside by the strong waves, as tracks were torn out as well, which gathered and piled high in twisted sculptures. The two stalled passenger trains were hit by the water and the lights went out as the water hit their battery boxes. The cars began to turn over one by one as the water rushed through the windows of the cars. Many of the passengers and crewmen of the trains escaped to a nearby coal car and stayed there during the night.

B. Milton Stearns, assistant chief dispatcher at Union Depot, had a level rod and kept a log of the rise and fall of the flood throughout the night. This may have been the only such record in existence. The water rose 3 1/2 feet between 11:30 and 11:45 pm. It reached a high of 9.75 feet above the floor at 11:55 pm. Because the floor of the depot was known to be at the river gauge height of 17.61 feet, it was possible to determine from his record the true high reached by the flood: 27.36 feet! (Denver Post Empire, July 15, 1956)

After the flooding ended on June 5, the flood would be known as the worst in Pueblo's history, with deaths between 150 and 250 people and more than $25 million in damage (the equivalent of $358 million in 2019). Civil engineers reshaped and changed the path of the Arkansas River to prevent future flooding. After the fires burned out, Puebloans had to deal with massive amounts of mud and thousands were homeless. All in all, the flood had inundated 300 square miles. Over 500 houses were carried away, along with 159 stores or businesses, 46 locomotives, and 1,274 railroad cars. There is no universally accepted death toll for the 1921 flood. Many Puebloans did not have family looking for them because they were single immigrants who came to work for the CF&I. Bodies were still showing up downstream from Pueblo months after the flood. Others were never found or went unrecognized when they did come in. The list of missing people was nearly twice as long as the list of the deceased, ranging from 50 in the days after the flood to nearly 300 in the following weeks. Some of those who were reported missing but escaped the deluge were never acknowledged as found. These complications made it difficult to determine how many lives were lost. Cleaning and rebuilding started as additional helped arrived from the Red Cross, Salvation Army, Knights of Columbus, and military units. Pueblo was put under federal control temporarily to restore law and order.

The 1921 flood was the worst of many floods on the Arkansas River, which averaged one flood every ten years until the building of the Pueblo Dam in 1970–75. That effort, part of the larger Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, created Lake Pueblo to allow for the storage and controlled release of water coming down the Arkansas River. While flooding on the Arkansas remains possible, the kind of flood that devastated Pueblo in 1921 would require enough water to overwhelm flood-protection infrastructure that can withstand five times as much water as in 1921. Water arriving along the river can also be held behind the 250-foot dam that created the lake (Colorado Encyclopedia). For a more detailed analysis of the flood, see the 1922 Department of the Interior, USGS Arkansas River Flood of June 3-5, 1921.

Comments

Please contact the

Please contact the Telecomunications History Group at 303-296-1221. They have information about the telephone operators who stayed in their building as a communications center during the flood to alert the community, saving many lives.

Thanks Kay, this is good to

Thanks Kay, this is good to know! Glad you read and enjoyed the article.

James

I am a civil engineer for the

I am a civil engineer for the Bureau of Reclamation and we use information from case histories like these to help us make our dams safer and develop emergency action plans. The purpose of these plans is to ensure communities/residents within the flood plane have adequate warning to take precautionary measures in case a significant flood occurs.

Hi Ron,

Hi Ron,

Thanks for your comment. I'm glad this blog could add to your case histories. Thank you for reading!

James

Add new comment