Posted on Behalf of Francis Lyon

It was only because I had been doing genealogical research that a stray book from Howard University caught my eye last month.

The book turned up without explanation on a shelf in the archive room at the Blair-Caldwell Branch Library, mixed in with a number of other items we were sorting through. Was it a lost ILL item? Or had it found its way here in a box, mixed in with donated items from someone’s home library? Nobody knew. But it had a bright red stamp saying Howard University—Founders Library. It was practically brand new, and still had a Howard University barcode sticker inside its cover. “Founders Library” sounded important. It sounded like something created by…well, the Founders. I pictured a beautiful room someplace, and in that room an unacceptably empty spot on one of the shelves. I pictured something like this:

...Which is exactly how one of the rooms in the Founders Library looks, in fact.

Howard University is an HBCU – a school designated by the U.S. Department of Education to be listed among America’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities. The website www.bestcolleges.com states that HBCUs are colleges that were established prior to 1964, “Rising from an historical environment of legal segregation” and founded “with the intention of offering accredited, high-quality education to African-American students across the United States.” As of January 2016, bestcolleges.com reports, there are 99 HBCUs to choose from; and the site rates Howard University, in Washington, D.C., as number one among those 99.

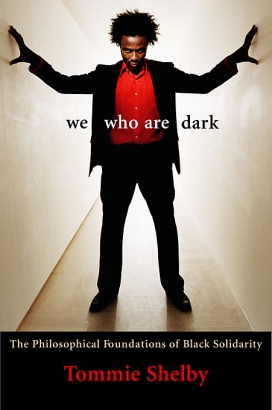

Howard was founded in 1867. It is a private university comprised of 13 schools and colleges, with no fewer than seven libraries within its library system—one of them the Founders Library, which opened its doors in 1939. The book that had somehow ended up at Blair-Caldwell was We Who Are Dark, written in 2007 by Harvard Philosopher Tommie Shelby. Googling the title revealed to me that a New York Magazine critic described Shelby’s book as a thoroughly researched argument for black solidarity that draws from “black political thought from W.E.B. DuBois to Malcolm X.” Its author went on to an academic career.

Clearly there was nothing to do now but…go online. Start Googling. From the Howard University home page I found my way to its Library System, and then to its online catalog (searchable); there I found a record for Shelby’s book. Its status: “Check Shelf.” Hmm. Sounds lost to me. Thinking that once upon a time the book might have been sent to Denver because of an Interlibrary Loan request, I decided to send an e-mail to the Howard University ILL Coordinator. (There is always a “Contact Us” button on every website someplace, making it all too easy in the heat of the moment to interrupt an ILL Coordinator in the middle of a busy day, e-mailing from a distant part of the United States to give him yet another thing to get done.) I heard back in 17 minutes. Yes, he said; please mail the book back to us. In those 17 minutes it had occurred to me that it might not be a bad idea to check with our own ILL department at DPL, too, so I e-mailed them as well. Another immediate response. There was no record of a request. But an ILL staff member, LenAnne Corcoran, offered get the book back to Howard University for me through the proper channels. Thank you LenAnne! Now I could rest easy.

But…no. None of that was why I found it so important for a book from Howard to find its way back to the Founders Library shelves, not really. The real reason was my favorite grandmother, Grandma Germaine. Somewhere in my genealogical research, unearthing facts about the death of my paternal grandfather, I could’ve sworn that I saw an article stating that Germaine, who was his second wife, had once been a professor at Howard University.

Trouble was, I couldn’t remember where I saw that article. I knew from the record of her death that Germaine was born in Paris, France. I didn’t know where or how she met my grandfather; I was only able to pick up the thread of her life in Washington, D.C., where I was a toddler when I first knew her. Germaine was a tall, elegant woman. She lived in D.C. with my grandfather and on Sundays, my family made the drive into the city from Virginia to visit them in their apartment. They served us dim sum pastry—a ritual for my father and his father (who had once lived in China, and married his first wife there). I preferred grilled cheese sandwiches to dim sum; and I adored Germaine. She understood the importance, for a toddler, of the question, “What did you bring me?” She was never empty-handed on Sundays. She’d always give me a brand-new toy, something small and fascinating, before we played our favorite game—in which gradually, a bit at a time and starting from a very narrow distance, we spread our arms wider and wider apart. The object of the game was to be the one always to reach the widest, every time, wider and wider, until your arms were as wide apart as they could possibly be. And at each stopping point in the game you said, each time more loudly: “I love you THIS much!”

The last time I visited Germaine, she was retired; my grandfather had passed away and she was living in Albuquerque, New Mexico. There was a lot we never got the chance to talk about, including how she found her way to Washington, D.C. (and possibly to teaching at Howard University.) But now it wouldn’t leave me alone. The finding of that one lost book had turned into the catalyst for a search that was about to open up a whole new chapter—because in the process of looking for proof that she had taught at Howard I found, by chance, something else that I had never known before: Germaine’s maiden name. Searching on Ancestry.com I found a record from Michigan of her marriage to my grandfather. It included not only her maiden name but the names of her parents. Finally, more of the story began to unfold.

My grandmother was born in Paris, France, but her parents were both from Germany. Germaine lost her mother when she was just 11 or 12, and after that U.S. Census records show that she came to New Mexico and became a U.S. citizen. She lived with relatives, or in college dormitories, and she set out on a teaching career that led her to Ohio and then to Michigan, where she earned a Master’s Degree in French and German (having already become fluent in Spanish along the way). In Michigan she met my grandfather, and from there they made their way to Washington, D.C. Much later, Germaine contacted a YWCA in Daytona Beach, Florida, where my grandfather had once taught Chinese classes. She made a donation to the YWCA in his memory, one that was reported in the Daytona Beach Morning Journal (which is now searchable using their online archives). The article that reported Germaine’s donation to the Y went on to state that she was “a retired professor from Howard University.”

So there it was. What languages she taught at Howard, and how long her career lasted there, is another research project. Until the end of her life, she lived surrounded by books. She’d have appreciated the effort to get a book back to where it belonged at Howard, I figure. I like the idea of having sent a book back to a library that my grandmother might once have visited, and of working with people who went out of their way to help me get it there. It just proves that you never know what the discovery of a lost book might lead to, and just how interconnected we all are.

But speaking of books, and libraries, and genealogical research. Ancestry.com can’t exactly bring back the real spirit of your relatives. But it sure does help to complete a picture of the life experience of someone you’ve only recalled until then through the memories of a child. And there are actual pictures on Ancestry.com, too, that can bring the memory of a beloved face rushing suddenly back to you.

Comments

Thank you, Francis. I enjoyed

Thank you, Francis. I enjoyed every aspect of this beautiful story.

Add new comment