On August 11, 1965, the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles blew up into a full-scale riot after the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) attempted to arrest a 21-year-old African American motorist named Marquette Frye. Frye’s mother, who lived nearby, showed up at the scene to scold her son but was manhandled by arresting officers instead. As Ms. Frye and her sons scuffled with the police, a growing crowd of onlookers joined in the fray, and the seeds of chaos were sown.

Over the course of the next six days, 34 people were killed, 1,032 were injured, and more than $40 million worth of property was destroyed. The Watts Riot/Rebellion scorched itself onto the nation’s collective memory. The fact that nearly 60 years later it’s still referred to as both the Watts Riot and the Watts Rebellion speaks volumes about Watts and its place in American history.

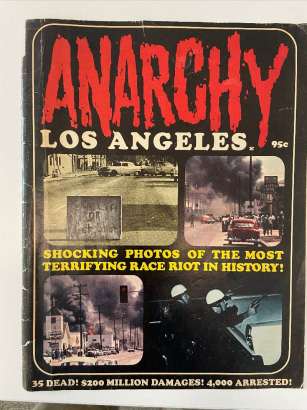

Anarchy, Los Angeles : shocking photos of the most terrifying race riot in history (323.1196073 Anarchy), a lavishly illustrated, 64-page publication published in 1965, and recently acquired by DPL for its Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library (BCAARL), falls squarely in the Watts Riot camp.

Though published just a few months after the events of August 1965, Anarchy Los Angeles foreshadows the fear-mongering that turned Watts into a lightning rod for racial conflict for decades to come.

Anarchy Los Angeles’ limited text stokes the fears of White America with passages like, “The pattern of destruction began to include widespread arson as early as the second night - Thursday - and burning almost immediately became the favorite activity of the mobs…Faces shone in the red glow, teeth glistened, and voices chanted, ‘Burn, baby, burn…burn, baby, burn’…”

In its rush to sensationalize, Anarchy Los Angeles entirely skips over the more complicated questions about racial segregation, police violence, and why a seemingly simple traffic stop could explode into such a devastating event.

In Oakland, a few hundred miles north of Watts, those complicated questions were very much on the minds of two young activists named Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seal, who founded the Black Panther Party just one year after the events in Watts.

In 1967, the Black Panthers began offering the American public a counter-narrative to mainstream media publications like Anarchy Los Angeles in the form of The Black Panther newspaper. The Black Panther presented the events of the day from the perspective of Black America and promoted an empowered view of people and neighborhoods that the mainstream media largely ignored.

Denver Public Library houses a collection of 42 issues of the Black Panther, from 1967 to 1975, at the Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library. Though much of its content focuses on California, the Black Panther was a national newspaper that told the stories of Black Americans in the Golden State and beyond.

For researchers of race relations, Western history, and media, Anarchy Los Angeles and The Black Panther provide an in-depth look at how two very different elements of American society viewed — and continue to view — race relations and racial unrest in the United States.

Anarchy Los Angeles and The Black Panther newspaper are available for public viewing at BCAARL.

Add new comment