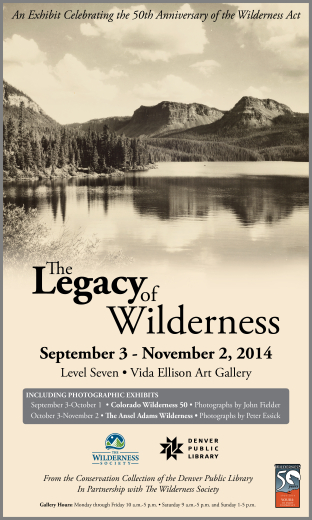

See all digitized items from the 2014 Legacy of Wilderness Exhibit in our digital collections.

The Wilderness Concept

American notions of wilderness have evolved over time. Before our modern understanding of “wilderness,” people’s relationships with the outdoors, nature or uninhabited lands varied widely. Early settlers in America thought of nature as a fearful unknown, inhabited by dangerous and savage creatures.

By the late nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution had drastically impacted the American landscape. Resources were being depleted, air and water were being polluted, and wildlife was being over-hunted or uprooted by disappearing habitat. Conservationists began to organize to preserve natural spaces for future generations. By the middle of the twentieth century, countries such as the United States, Canada, and Britain created legislation in order to ensure that the most fragile and beautiful environments would be protected for generations to come. Today, there is a stronger movement taking place, with a deeper understanding of habitat conservation with the aim of protecting delicate habitats and preserving biodiversity on a global scale.

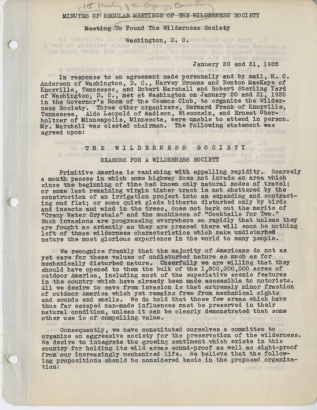

Founded in 1935, The Wilderness Society has led the effort to permanently protect nearly 110 million acres of wilderness in 44 states. In many ways, the history of The Wilderness Society—from Bob Marshall and Aldo Leopold, to the Muries and Howard Zahniser—is the history of the National Wilderness Preservation System.

Today, The Wilderness Society is supported by more than 500,000 members, and the National Wilderness Preservation System is enjoyed by millions of Americans.

As part of its renowned Conservation Collection, the Denver Public Library is home to The Wilderness Society’s archives, from which many of the historical documents are drawn for “The Legacy of Wilderness: An Exhibit Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the Wilderness Act.”

In 1920, Trappers Lake was designated as an area to be kept roadless and undeveloped – and it remains so to this day. The Flat Tops Primitive Area was established on March 5, 1932. Although the primitive area designation was not viewed as a general measure for wilderness protection, it was seen as an interim way to protect key lands. On September 3, 1964, the United States did something that no other nation had ever done before. They created “The Wilderness Act.” The act states:

In order to assure that an increasing population, accompanied by expanding settlement and growing mechanization, does not occupy and modify all areas within the United States . . . leaving no lands designated for preservation and protection in their natural condition, it is hereby declared to be the policy of the Congress to secure for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness.

The 235,214-acre Flat Tops Wilderness was established on December 12, 1975 and is the second largest Wilderness area in Colorado.

It is no wonder Arthur Carhart (see exhibit section below about Arthur Carhart, the first to propose a wilderness area at Trappers Lake) found the area so entrancing: behind Trappers Lake loom majestic volcanic cliffs, and beyond them the vast sub-alpine terrain yields to alpine tundra. Approximately 110 lakes and ponds, many unnamed, dot the country above and below the numerous flat-topped cliffs, and roughly 100 miles of fishable streams can be found in the Wilderness area.

The fight over building the Echo Park Dam in Colorado was directly linked to the passage of The Wilderness Act. In 1950, the Bureau of Reclamation and western water interests proposed building a large dam on the Green River in the backcountry of Dinosaur National Monument in northwestern Colorado. The dam would have led to the flooding of the Echo Park area known and loved for its wilderness qualities.

Conservation organizations drew a line in the sand. The Wilderness Society and Sierra Club led impressive public campaigns to fight against the dam proposal on the principal that there should be certain public lands and waters that remain off-limits to industrial development, left for people to enjoy as they are.

The conservationists won the day and the dam was never built at Echo Park. However, it was a battle fought in the court of public opinion as there were not sufficient legal tools to protect such a place from development yet. The five-year battle over the dam set the stage and provided momentum for debates over The Wilderness Act—the first draft of which was penned just a few months after the bill to authorize the Echo Park Dam was killed.

“If we are to have broad-thinking men and women of high mentality, of good physique and with a true perspective on life, we must allow our populace a communion with nature in areas of more or less wilderness condition.” - Arthur Carhart

A champion for wilderness in Colorado, Arthur Carhart's legacy is tied to the successful preservation of Trappers Lake (see exhibit section on Trappers Lake above.) In 1919, the U.S. Forest Service hired Arthur Carhart as its first full-time landscape architect, though his formal title was "recreation engineer." One of his first assignments was to survey a road around Trappers Lake in Colorado's White River National Forest, to identify one hundred summer home sites on the lakeshore. Carhart completed the assignment, but he recommended to his supervisor Carl Stahl that no development be permitted on the shore.

“There are a number of places with scenic values of such great worth that they are rightfully the property of all people. They should be preserved for all time for the people of the Nation and the world. Trappers Lake is unquestionably a candidate for that classification.”

Carhart urged that the best use of the area was for wilderness recreation. This was a bold suggestion for such a young employee and Carhart was quite surprised when his supervisor endorsed his recommendations. In an unprecedented move, the Forest Service set the plans aside for further study, and the proposed homes and road were never built. Because of this, some considered it the birthplace of the U.S. Wilderness Area system, and Trappers Lake has been called the “Cradle of Wilderness.”

Carhart's ideas and vision were shared by another individual who became a significant figure in the wilderness movement: Aldo Leopold, then Assistant District (Regional) Forester for District 3 (Region 3) in New Mexico. On December 6, 1919, Leopold visited Carhart in Colorado. Inspired by their talks, Carhart wrote what was then simply titled “Memorandum for Mr. Leopold, District 3,” a memo later considered to be one of the most significant records in the history of the wilderness concept.

Arthur Carhart left the Forest Service in 1923 to pursue private practice in landscape architecture, city planning and writing. Before leaving the Forest Service, however, he toured the Quetico-Superior region in Minnesota and recommended these areas of superlative wild scenery be managed for their value as wilderness. Carhart's efforts eventually led to development of what is now the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. Another lasting legacy Carhart left behind is the Denver Public Library's Conservation Collection which he helped to found in 1960.

“The wilderness that has come to us from the eternity of the past we have the boldness to project into the eternity of the future.”

- Howard Zahniser, testimony in Wilderness Preservation System hearing (1964).

Howard Zahniser was the legendary leader of The Wilderness Society who drafted the Wilderness Act of 1964 and was one of its chief advocates. He led The Wilderness Society through two decades of wilderness battles and landmark accomplishments, including the effort to protect Echo Park in Dinosaur National Monument in Colorado from dams.

Zahniser joined The Wilderness Society in 1945, first serving as executive secretary and editor of the organization’s magazine, The Living Wilderness, and later as the organization’s executive director.

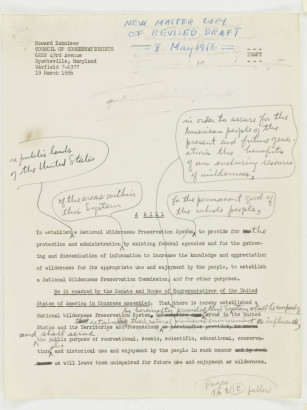

A consummate writer, Zahniser wrote more than 60 drafts of the Wilderness Act between 1956 and 1964, attended all 18 congressional hearings on the Act, personally lobbied virtually every member of Congress, wrote numerous articles, and delivered critical speeches in the effort to pass the Wilderness Act. Zahniser died of heart failure just five months shy of seeing President Lyndon B. Johnson sign the Wilderness Act on September 3, 1964.

Olaus Murie (1889-1963)

“It takes maturity to really accept the unimportance of human achievements, or to recognize how much humans do not know, or to understand that it’s sometimes best to leave things alone.” – Olaus Murie

Olaus Murie was a renowned biologist and one of the country’s great champions of wildlife and wilderness. Scientist, visionary, and former governing council member and president of The Wilderness Society, Olaus Murie’s vision helped establish the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska and shaped a new way of thinking about predators and ecosystems. Olaus was a wildlife biologist studying caribou when he met his lifetime companion, Mardy, a native Alaskan. The Muries moved to Jackson Hole, Wyoming to study the local elk herd and it became their lifelong home. Olaus became an early, staunch defender of predators and their crucial role in ecosystems.

In 1950, The Wilderness Society named Murie as its president. The Muries’ log cabin in Moose, Wyoming became an unofficial Wilderness Society headquarters. As president, Murie lobbied successfully to prevent large federal dam projects within Glacier National Park and Dinosaur National Monument.

Murie’s greatest quest became protecting the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in northeast Alaska. In 1956, Mardy, Olaus, and a few others spent several weeks on an Arctic expedition. Armed with their evidence, they returned to the lower 48 and spent four years campaigning tirelessly to protect the place so dear to them. In 1960, President Eisenhower set aside 8 million acres as the Arctic National Wildlife Range, which later became part of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

In 1964, just months after Olaus died, President Johnson signed the Wilderness Act, creating 9 million new acres of protected lands.

Mardy Murie (1902-2003)

“Beauty is a resource in and of itself. … I hope the United States of America is not so rich that she can afford to let these wildernesses pass by, or so poor she cannot afford to keep them.” - Mardy Murie, congressional testimony on the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act.

Mardy Murie, “Grandmother of the Conservation Movement,” was a committed lifelong conservationist and protector of wildlife and wild lands. Wife of former Wilderness Society President Olaus Murie, Mardy Murie was a wilderness warrior in her own right, serving on The Wilderness Society governing council, and advocating for wilderness in Alaska and beyond throughout her life.

Margaret (Mardy) Murie was born in Seattle in 1902 and moved to Fairbanks, Alaska while she was still young. She was the first woman to graduate from the University of Alaska at Fairbanks in 1924, the same year she married Olaus Murie. Their honeymoon was a caribou research expedition by dogsled in Alaska's Brooks Range within the Arctic Wildlife Range.

It became second nature for Mardy to pack her babies along with her camping gear for trips accompanying Olaus in the Alaska wilds. Mardy described the family's Alaska adventures in her book Two in the Far North.

Mardy attended the signing of the Wilderness Act by President Lyndon Johnson after Olaus’ death. She was awarded the Medal of Freedom by President William Clinton in January 1998 for her lifelong commitment to conservation.

“In order to escape the whims of politics … [wilderness areas] should be set aside by act of congress, just as national parks are today set aside. This would give them as close an approximation to permanence as could be realized in a world of shifting desires.”

—Bob Marshall, “Suggested Program for Preservation of Wilderness Areas”

Memorandum to Secretary Ickes (April 1934)

Robert Marshall, principal founder of The Wilderness Society, set an unprecedented course for wilderness preservation in the United States that few have surpassed.

Marshall shaped the world’s first policy on wilderness designation and management. He wrote passionately on all aspects of conservation and preservation; his writings detailed the aesthetic value of wilderness to humankind and pushed for public ownership.

A voracious outdoorsman, he was famous for his hiking endurance—once walking 70 miles in a 24-hour period to make connections for a trip. Marshall was also a prolific writer.

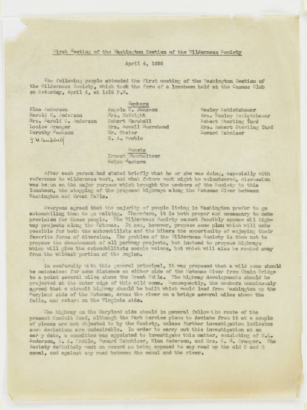

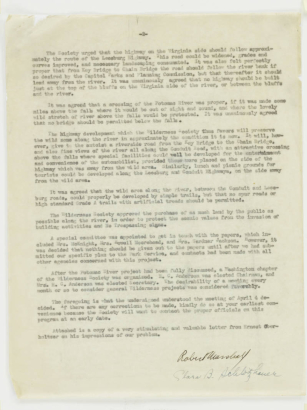

Bob Marshall called for an “organization of spirited people who will fight for the freedom of the wilderness” in 1930, a call that was heeded in 1935 when he helped co-found The Wilderness Society. He continued to keep the organization solvent and steered its course until his untimely death at age 38. The following year, the Forest Service reclassified and renamed three primitive areas in Montana as the Bob Marshall Wilderness.

“When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.”

- Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac (1949)

Aldo Leopold joined the Forest Service in 1909, advancing in the ranks as a ranger and supervisor in New Mexico. By 1919, his thinking had evolved from a narrow focus on forestry and wildlife management to an expanded awareness of the need to protect wilderness in America.

In 1933, the University of Wisconsin offered Leopold a professorship to teach in the nation's first graduate program in wildlife management. Two years later, with the rapid loss of wilderness in America weighing heavily on his mind, Leopold joined seven other leading conservationists to form The Wilderness Society.

A prolific writer, Leopold conceived of a book geared for general audiences examining humanity’s relationship to the natural world. Just one week after receiving word that his manuscript would be published, on April 21, 1948, Leopold died of a heart attack while fighting a neighbor’s grass fire.

A little more than a year after his death, Leopold’s collection of essays was published as A Sand County Almanac, which to this day serves as a guiding beacon for The Wilderness Society and many other conservation advocates.

“In order to escape the whims of politics … [wilderness areas] should be set aside by act of Congress, just as national parks are today set aside. This would give them as close an approximation to permanence as could be realized in a world of shifting desires.” - Bob Marshall, “Suggested Program for Preservation of Wilderness Areas,” Memorandum to Secretary Ickes (1934).

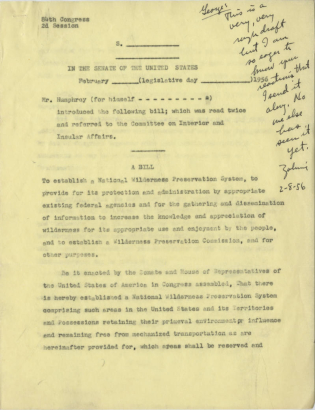

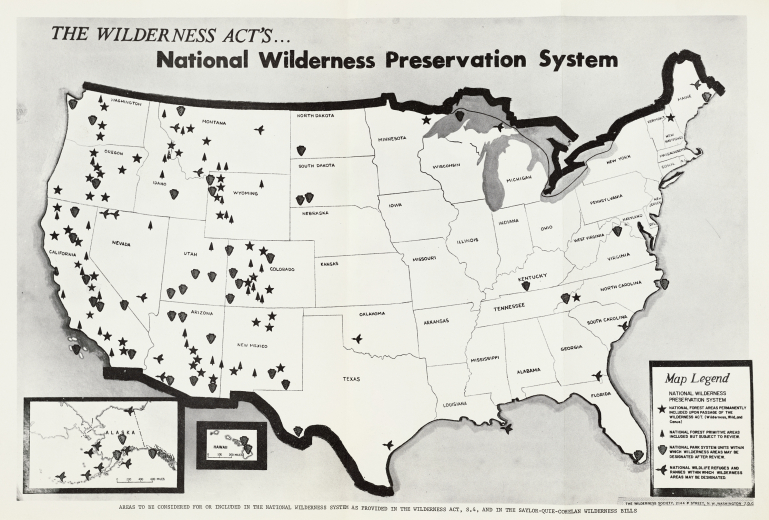

The Wilderness Act of 1964 was the culmination of nearly 50 years of advocacy by Aldo Leopold, Bob Marshall, Arthur Carhart, Olaus and Mardy Murie, Howard Zahniser, and others. Building on Bob Marshall’s 1934 proposal for congressional establishment of wilderness areas and responding to his own plea in 1955 that “[a] bill to establish a national wilderness preservation system should be drawn up as soon as possible,” Howard Zahniser began drafting such a bill to protect areas “retaining their primeval environment or influence and remaining free from mechanized transportation.”

In June of 1956, the first two bills were formally introduced. It took eight years, many bills and hearings, much compromise, enormous persistence, skillful advocacy, and broad public support to pass a wilderness act.

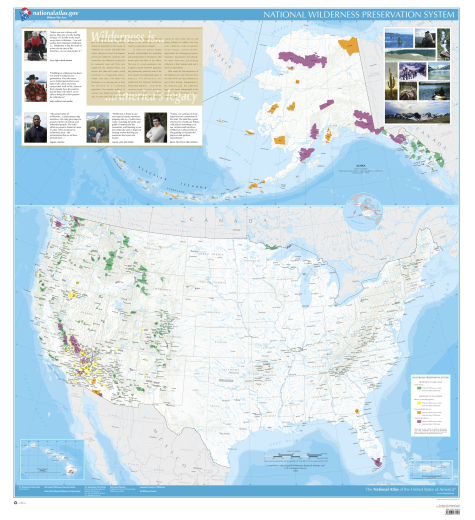

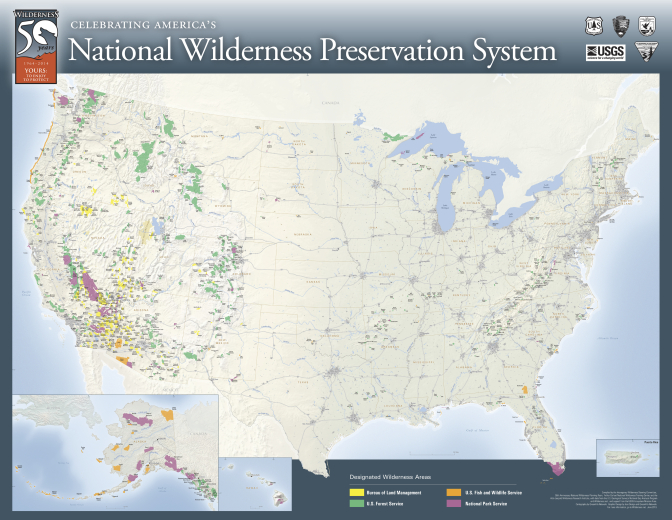

The 1964 Act established 54 wilderness areas protecting 9.1 million acres in 13 states. Today, half a century later, the Wilderness Act has left the American people with a growing legacy of 758 wilderness areas protecting more than 109.5 million acres in 44 States and Puerto Rico, where millions of Americans enjoy hiking, hunting, camping, backpacking, fishing, and more.

In 2014, more than two dozen bills to add to the National Wilderness Preservation System are pending in Congress, including bills that would protect wilderness in Colorado’s Hermosa Creek watershed, Browns Canyon, the San Juan Mountains, and the Central Mountains.

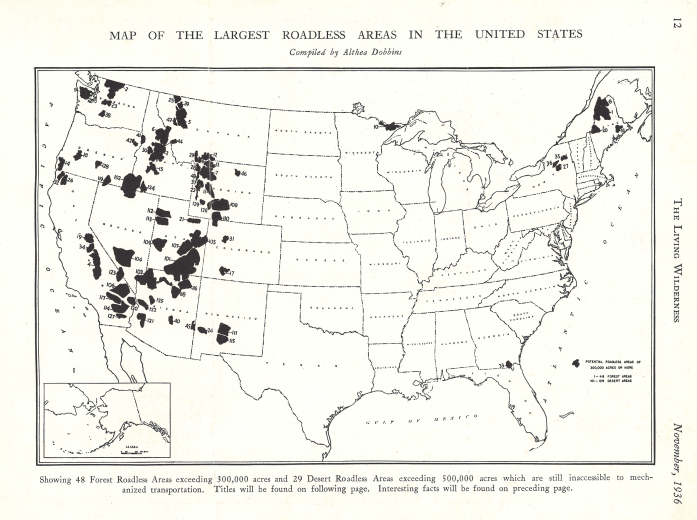

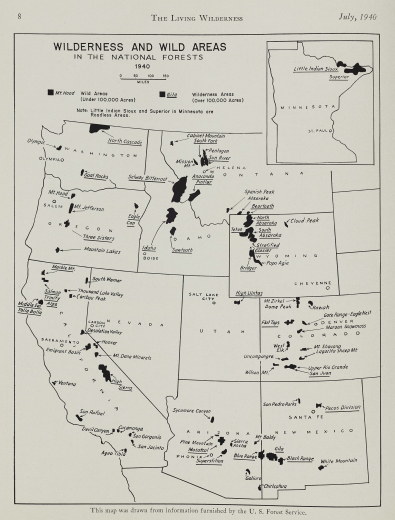

From Robert Marshall’s pioneering work to inventory roadless landscapes in the 1930s to the National Wilderness Preservation System on its 50th Anniversary, this historical perspective illustrates the paradox between the persistent shrinking of America’s remaining roadless landscapes and the unrelenting effort to expand the National Wilderness Preservation System to protect what remains.

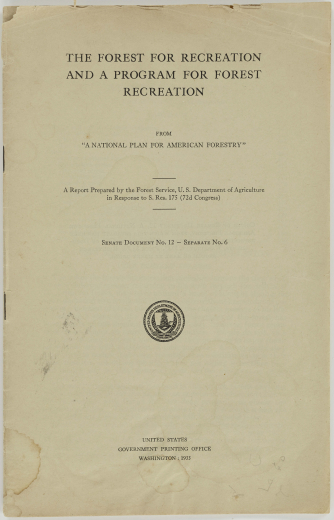

Bob Marshall spent years of his short life exploring and mapping roadless landscapes across the United States. His important chapter on recreation in this influential report (commonly known as “The Copeland Report”) represents the first significant effort to publish the geographic scope of America’s remaining roadless landscapes.

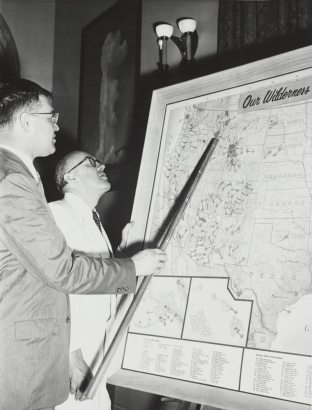

- While it was not unusual for early maps of the United States to label uncharted territory as “Wilderness”, Marshall and Dobbins’ 1936 map may be the first map to chart America’s remaining wilderness in an effort to protect it as such.

- While the early focus of wilderness advocates was on National Forest and National Park lands, this inventory and map are also notable for their consideration of the desert landscapes of the southwest, such as the red rock country of southeast Utah. The map depicts 48 forested areas larger than 300,000 acres and 29 desert areas larger than 500,000 acres.

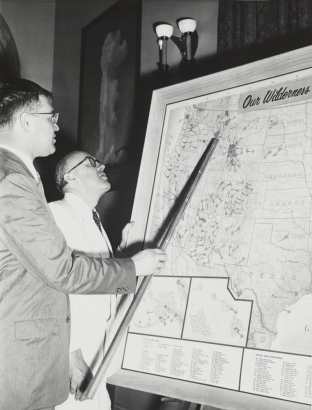

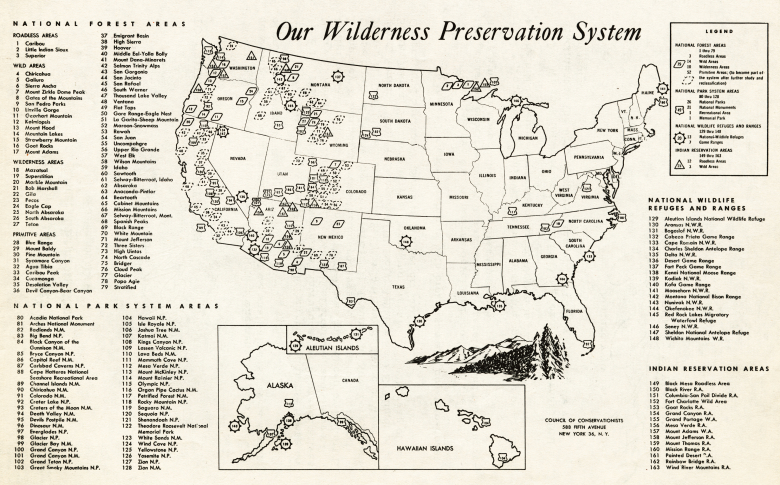

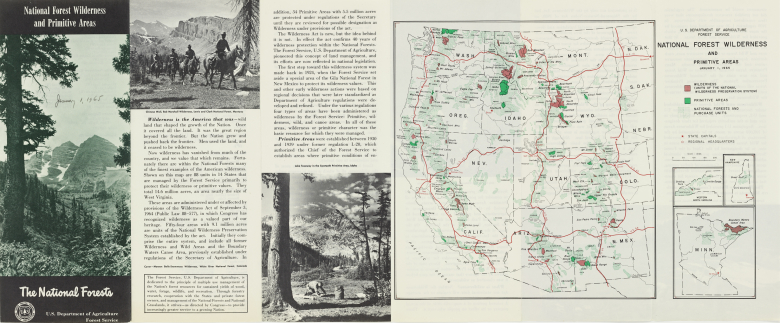

This map, published by The Wilderness Society in 1964, illustrated the locations of areas that would be protected and considered for protection under proposed legislation in the House and Senate. On August 20, 1964, the amended Senate bill (S.4) was passed in both chambers by a simple voice vote and sent to the President, who signed the bill into law on September 3, 1964.

This brochure illustrates the National Wilderness Preservation System, established on September 3, 1964. Looking to the areas that had been identified for protection pursuant to Bob Marshall’s U-Regulations,* section 3(a) of the Wilderness Act provided: “All areas within the national forests classified at least 30 days before September 30, 1964, by the Secretary of Agriculture or the Chief of the Forest Service as ‘wilderness’, ‘wild’, or ‘canoe’ are hereby designated as wilderness areas.”

![Peck is accepting Carhart's proposal to limit development around Trappers Lake. "I fully agree that features of superlative interest belongs to all the people and should be protected from selfish individual use; we have a real duty in this regard. I cannot say just how absolute we should make our rule re: Trapper's Lake as I haven't seen it, but feel we should take the safest course, and am willing to concur in your plan tentatively. A.S.P." [initials of A.S. Peck, then Regional Forester R-2, Denver]](/sites/history/files/styles/blog_image/public/cdm_420.jpg?itok=kUBNz2Bp)

Add new comment