Denver is known for its parks and parkways and for the many wonderful residential neighborhoods that have endured close to the heart of the city. The East 7th Avenue Historic District preserves one central neighborhood and three pieces of the park system. With the exception of a few earlier buildings, the district was built primarily from the 1890s through 1930. The district grew out from the core city.

Though it is Denver’s largest historic district, it is only two blocks wide for most of its length. The district runs from Logan Street to Colorado Boulevard and from East 6th to East 8th Avenues. From Steele to Harrison Streets, its width is confined to the East 7th Avenue Parkway and to those homes that border the parkway.

The historic district claims its borders from a sense of neighborhood reinforced over the years by streetcar and bus lines using East 6th and East 8th Avenues, from parks bordering these avenues, and from early Denver city limits along East 6th Avenue. The old town of Harman bordered the district on East 6th Avenue between Josephine and Colorado Boulevard. A special tax district to pay for the East 7th Avenue Parkway in 1912, plus various early neighborhood organizing efforts, also contributed to a neighborhood identity. In 1958, East 6th and East 8th Avenues became one-way streets, giving families within the two-block- wide strip an even stronger sense of neighborhood.

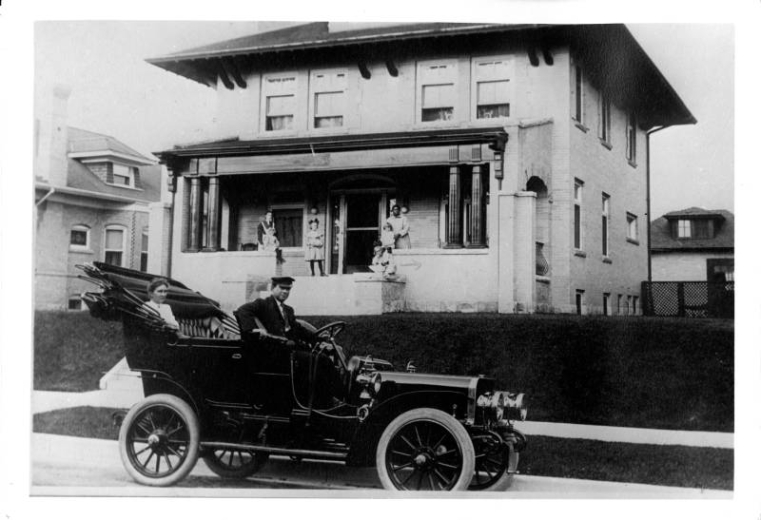

Original district residents were a mix of business and professional people, entrepreneurs and clerks, socialites and laborers, wealthy and middle class. It was common to have mansions on the corners and more modest homes, duplexes, and terraces scattered among them. When the parkway was created in 1912, the larger homes tended to be built on the parkway, with smaller homes on the north-south streets. Most of Denver’s finest architects worked in the district and many chose to live there.

The district was developed at the height of the City Beautiful Movement. Just as district development reached Williams Street, the plan was implemented, creating the East 7th Avenue Parkway and the Williams Street Parkway. The city bought the parkway land in 1912, redesigned the streets, and hired an outside consultant to work with city landscaper Saco DeBoer to design the plantings. The Frederick Law Olmsted firm, designer of New York’s Central Park, was the consultant.

Three park system elements are in the district: East 7th Avenue Parkway, the Cheesman Esplanade, and Williams Street Parkway. They help connect Cheesman Park, City Park, and Washington Park. Only one parkway residence, at 2401 East 7th, was built before East 7th Avenue Parkway was created. It is the only parkway house built close to the street because in 1908 the setback requirement did not yet accommodate the parkway plan. Three Denver Square–style homes were built on the east side of the 600 block of Williams Street in what is now the grass-covered parkway. They were moved by the Denver Wrecking Company in 1912 and now stand on the west side of the 600 block of High Street.

DeBoer designed the plantings on the 7th Avenue median and Olmsted designed the double row of elm trees along each side of the parkway to form the high tree canopy. Many of these original elms are still there, and most of DeBoer’s scheme is still in evidence with his many garden “sun spots” planted annually by city landscapers. The 1912 planting went from Williams to Milwaukee Streets. The second planting in 1927 completed the planting installation to Colorado Boulevard.

Mamie Doud and Dwight D. Eisenhower were married in the living room of this home at 750 Lafayette Street in 1916. This was the home address for Ike and Mamie throughout Eisenhower’s military career, and it became the Summer White House during the Eisenhower administration. Mamie had attended Dora Moore School, and the Douds were members of Corona Presbyterian Church at 8th and Downing. Ike and Mamie had many Denver friends in the district, and would often join them for dinner at their homes. District residents recall the motorcade parading down East 7th for President Eisenhower’s arrivals and departures. Lafayette Street residents remember Eisenhower grandchildren and Nixon children playing in neighborhood yards. They also remember the friendly nature of the Secret Service guarding the president in a more relaxed era. Mamie’s girlhood home was built by her parents, stockman John Doud and Elvira “Miss Min” Doud. The Doud House and its two neighbors to the south are fine examples of Denver Square variations.

Widmann, Nancy L., and Cynthia S. Herrick. The East 7th Avenue Historic District. Denver, CO: Historic Denver, 1997. Print.

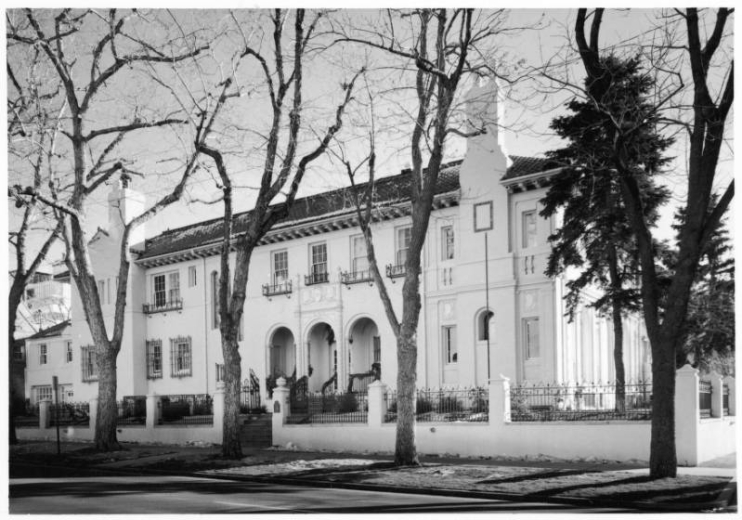

The Governor’s Mansion was planned by millionaire Walter Scott Cheesman, who arrived in Denver in 1861 and first made his mark dealing in water, early Denver’s most needed commodity. Cheesman diversified into numerous areas, protecting his wealth through behind-the-scenes political dealings in concert with other wealthy businessmen. He died in 1907, never to see his stately mansion. Architects Marean and Norton so impressed his widow with their design of the Cheesman Park Pavilion that she hired them to replace Gove and Walsh as mansion architects. Marean and Norton were active in Denver’s City Beautiful Movement, both serving on the Denver Art Commission, the initial planning agency for Denver’s park system.

In 1908 the mansion was the scene of an exchange of wedding vows uniting two powerful families. Cheesman’s daughter, Gladys, wed John Evans, grandson of Territorial Governor John Evans. The newlyweds shared the 24,000-square-foot mansion with Cheesman’s widow, Alice, until 1911, when their larger mansion overlooking the Denver Country Club was completed.

When Alice Cheesman died in 1923, Claude and Edna Boettcher bought the residence for $75,000. Claude and his father, Charles Boettcher, ran the Great Western Sugar Company, Ideal Cement Company, Boettcher Investments, and a realty company. Claude and Edna died in the late 1950s, and the Boettcher Foundation gave the home to the state for use as the governor’s mansion. In 1960, Governor Stephen McNichols became the first governor to occupy it.

Landmarked locally in 1968, this twenty-seven-room mansion retains estate grounds designed by Kansas City landscape architect George Kessler. In 1979, part of Pennsylvania Street was used to create Governor’s Park to offer a grass-covered connection to the Grant-Humphreys Mansion.

Widmann, Nancy L., and Cynthia S. Herrick. The East 7th Avenue Historic District. Denver, CO: Historic Denver, 1997. Print.

738 Pearl Street, a Georgian Revival mansion built in 1905 at a cost of $16,000 by architects Frederick J. Sterner and George Williamson, is known as the "Foster-McCauley-Symes House." The first owner, investment banker Alexis C. Foster, spurred by concern for the causes of war, helped to finance the origins of the University of Denver's School of International Studies. The third owner was U.S. Court District Judge J. Foster Symes. In 1956, the home became the French Consulate under Louis Baron de Cabral. The architects specified red, hand-cast sand bricks with "butter joints," thin mortar joints no wider than 1/8". Note the Palladian window incorporated into the third floor gambrel roof dormer.

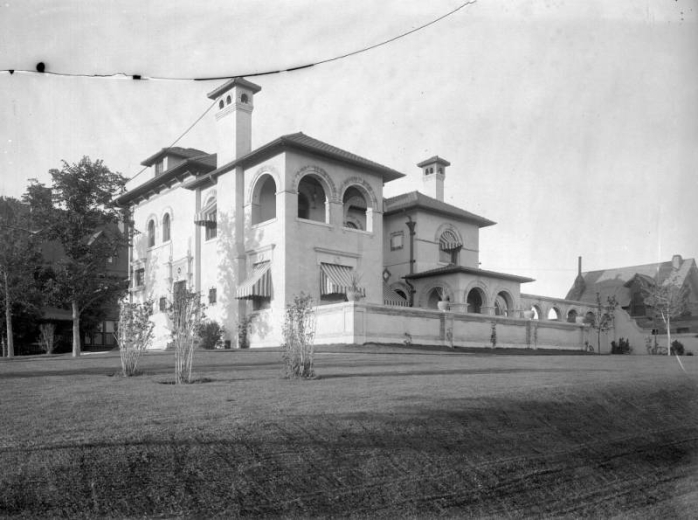

The Wood-Morris-Bonfils Mansion, at 707 Washington Street, is a French Mediterranean Revival style home built in 1909-11 by architects Maurice Biscoe and Henry H. Hewitt, at a cost of $25,000. Cripple Creek gold provided the wealth Guilford S. Wood used to build his fifteen-room mansion. The next owner, P. Randolph Morris, involved with railroads and Union Station, sold it to Denver Post owner and philanthropist Helen Bonfils and her husband, George Somnes, in 1947. After later ownership by Phillis McGuire (of the singing McGuire Sisters), the mansion became the Mexican Consulate during the 1980s. An ornate wall along 7th Avenue once defined lovely gardens cascading eastward. Daniel Havekost designed the 1987 condo appendage now standing in place of the gardens. Next door at 727 Washington, Biscoe and Hewitt also designed the Edwin Kassler House, dubbed an "American Newport" design in 1910.

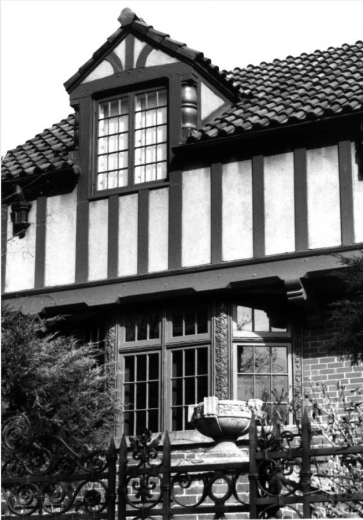

This English Tudor style house at 720 Emerson Street was built in 1906 by architects Aaron M. Gove and Thomas F. Walsh at a cost of $10,000, and the original house plans have been passed down from the original owner, Mary A. Alkire, to this day. The second owners, James and Winifred Owen, commissioned a 1926 remodel by Burnham Hoyt, which, in part, removed a front porch roof. The Owen family crest remains above the front door. James Owen was a Colorado Supreme Court judge. Following this remodel for Owen, Hoyt went to New York City, where John D. Rockefeller, Jr., commissioned him to design Riverside Church on Morningside Heights. Hoyt stayed in New York until 1936 as dean of the New York University School of Architecture.

The house at 930 East 7th Avenue is a Mediterranean Revival style residence built by architects William F. Fisher and Arthur A. Fisher for oil man Charles Orchard and his wife Mabel in 1910-11 at a cost of $17,000. Stone quoins at the corners and second-floor balconets accent the structure, which betrays a strong French influence in its steep roofline. The original plans are in the Fisher and Fisher Collection at the Denver Public Library.

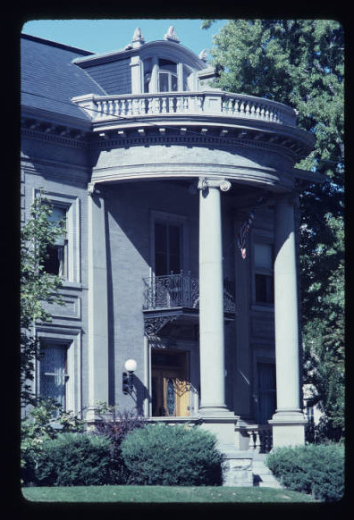

The Grant-Humphreys Mansion, a Neoclassical home built in 1901-2 at a cost of $75,000, was designed by by architects Theodore D. Boal and Frederick L. Harnois. The original owners for whom the house was designed, James and Mary Grant, placed their forty-two mansion majestically on a hill with a mountain view protected now by the creation of Governor's Park. James Grant owned the Omaha & Grant Smelter and was the state's first Democratic governor (1883-1885). Albert E. Humphreys, a wealthy oil man and second owner in 1917, was involved in the Teapot Dome Scandal of the 1920s. He reportedly died of an accidentally self-inflicted gunshot wound in the mansion in 1927.

Albert's son, Ira Boyd Humphreys Airplane Company, which offered Colorado's first commercial flights. For $12.50, flights took daring passengers to Cheyenne, Estes Park, and the Broadmoor Hotel in 1920. The open-cockpit adventure was not for everyone, but 3,500 passengers thrilled to the challenge until the hangar and three planes were destroyed by fire in 1921.

Terra-cotta trim, in place of stonework, offered a new design material at the time. The trim decorates the light-colored brick mansion in the balustrades, window surrounds, corner pilasters, and spectacularly, in the two-story Corinthian columns that support a massive semicircular portico. The mansion's scale was matched by Albert Humphrey's addition of a ten-car, two-story garage to house his collection of Rolls-Royce autos. In 1976, Humphreys gave the mansion to the Colorado Historical Society [now History Colorado]. Visitors are welcome to stop in and see this house museum, which also is available as an elegant setting for weddings, receptions, holiday parties, meetings, and retreats.

Two district mansions border Governor's Park on East 8th Avenue: the Malo Mansion at 500 East 8th, and the John Porter House at 777 Pearl. Oscar Malo owned the Colorado Milling and Elevator Company. His 1921 home was designed by Harry Manning. John H. Porter chose Varian and Varian to design his 1917 Jacobean-style house.

John A. Ferguson used his invention of pressurized brick block and cement to build the guest house for his now-demolished mansion at 700 Washington Street. Ferguson was a founder of the Denver Country Club and later helped establish the Country Club neighborhood. George W. Gano, of Gano-Downs Clothing Stores, bought the house in 1909. The Mediterranean Revival style structure was designed by architect Theodore D. Boal and built in 1896.

The John C. Mitchell house at 680 Clarkson Street was designed in an eclectic style by an unknown architect and built in 1893, with a 1915 addition by George L. Bettcher, and a 1973 apartment conversion by Daniel Haverost.

Classical ornament and high mannerist dentils at the roofline distinguish the Victorian asymmetry of this eclectic design. John Clark Mitchell came to Colorado from Illinois and was a banker in the San Juans, Durango, and Leadville. He called this house "Trail's End." Mitchell donated the Sullivan Gateway located on the City Park Esplanade entrance to East High School. The Mitchell family owned the house until 1945. The 13,000 square-foot house was converted into apartments in 1973, and the landscaping within the black wrought-iron fence was designed by district resident Jane Silverstein Ries.

The Adolph J. Zang Mansion, at 709 Clarkson Sstreet, is in the Neoclassical style, and was designed by architect Frederick C. Eberley, and built in 1902-4 at a cost of $108,000.

Adolph Zang, whose father owned a Denver brewery, invested in Cripple Creek mines and the Oxford Hotel and helped create Denver's 1903 home rule charter. His world travels allowed him to lavishly furnish the mansion. Rooms were each designed around an individual them incorporating tiles, a variety of woods, elaborate carvings, and oil paintings on silk fabric. These features and stained-glass windows are preserved. Adolph's wife, Minnie, lived in the house until her death in 1949. The Mormon Church moved its Denver headquarters from its original distric location at 538 East 7th to occupy the home until 1977. The extravagantly appointed interior provides elegant office space today. Here is more information about the Zang Mansion.

The information regarding the East 7th Avenue Historic District is pulled primarily from a Historic Denver Guide, East 7th Avenue Historic District. Historic Denver, Inc. has published a number of guides for the various historic districts and building styles in Denver. These guides can be purchased at Historic Denver. The guide for East 7th includes more information and tours of the area. More information on the City Beautiful Movement can be found in Denver, The City Beautiful by Thomas J. Noel and Barbara S. Norgren, also available on the Historic Denver and Denver Public Library's Western History websites.