While not an officially zoned neighborhood, Curtis Park’s history and legacy remain captivating. As part of the greater Five Points neighborhood, Curtis Park is one of Denver’s oldest districts. Many different communities have called this area home over time, and a walk through its streets today paints a spirited and complex picture of its historic structures and charm.

Though the Victorian-era homes that still stand harken back to a time when architectural beauty hinged on the small and ornate details, Curtis Park’s legacy is also steeped in racist policy. As we continue to unravel the many iterations of this vibrant area, we would be remiss not to acknowledge the racist practices of redlining that not only shone a light on the resilience of Curtis Park’s residents but also continue to impact the lives of residents in today’s rapidly changing Denver.

The neighborhood is just to the northeast of downtown Denver, and is called Curtis Park for the city park in its midst, is the creation of the city's first golden age, that time between 1870, when the railroad came to town, and 1893, when the Silver Crash brought a rude end to Denver's early prosperity. During that brief period, the rate of Denver's population growth was higher than that of any other city in the country. From a modest 4,759 in 1870, just twenty years later, in 1890, the city had 106,713 inhabitants. One historian has called it an "instant city."

Denver's incredible growth was matched by its optimism about the future. Already in 1871, just a year after the railroad arrived, the first streetcar line, equipped with horse-drawn cars, was laid out. Beginning at 7th and Larimer Streets, it eventually turned onto Champa at 16th and continued up that street until it reached 27th. At the time of its initial construction, the extension of the line along the still-unpaved Champa Street must have seemed like a shot in the dark, to serve little or no purpose unless it was to transport revelers out to Billy Wise's National Park, a resort at the end of the line where, east of the city limits, "suppers for private parties" and "the purest and best liquors" awaited. A reporter for the Rocky Mountain News wrote, in the streetcar line's first year of service, that a new suburb would surely arise along its path. He also noted, however, that the land it served was, in its present state, "remote and unvaluable."

But Denver's population explosion had created a housing boom that was about to sweep away any and all traces of Billy Wise's pleasure grounds. In 1879, when another reporter from the News rode the line all the way to its terminus at 27th and Champa, he found conditions along the line had changed dramatically. "The spirit of improvement," he wrote, "is unabated." Wherever he looked he noticed "substantial brick residences" being built. What he was witnessing was the amazing growth of the Curtis Park area.

By the time of Robinson's 1887 real estate maps, which show all the developed property in the city by that date, the majority of the houses between downtown and Downing Street, where Denver's original street grid comes to an end, had already been built. In a mere ten years or so, there had appeared on the arid, treeless prairie northeast of the original town settlement a superb collection of late nineteenth-century houses, rows of them one after another, on the closely platted streets.

The population that flowed into what has been called Denver's first streetcar suburb was fed by immigration from abroad and migration within the States. The newcomers arrived from Vermont, Virginia, Germany, and Ireland. Many who came were adventurers, men drawn by the lure of a new territory to tame and settle, perhaps to grow rich in. The story of Vincent Markham may be taken as illustrative. When he died in his home at 2611 Stout in 1895, one of those who remembered him wrote, in the florid manner of the period, that he left Virginia because "moved by the impulse ... that stirred his Norman ancestry to activity and adventure, he decided ... to seek his fortunes in the West, for ... he was possessed of ambition."

The young city that sprang up within sight of the mountains where gold had been discovered was too new, in too much of a hurry, to worry about living arrangements that noticed social and economic distinctions. An easy tolerance seems to have prevailed. To be sure, those who lived in Curtis Park appear to have been a fairly homogeneous group of western and northern European extraction; but there were considerable economic differences among them, still apparent in the houses they built, some large and lavish, others small and modest. Well-to-do railroad men lived in close proximity to blacksmiths, and prosperous businessmen next door to bank clerks. Mrs. Josephine Brauch, who lived out her long life in the house at 2627 Champa where she was born, remembered another kind of tolerance. Her family was Irish Catholic, but her mother would not allow the children to play in their front yard on Saturday mornings in deference to the Jews who would be walking past on their way to the synagogue at Curtis and 24th.

Curtis Park's golden age lasted a scant twenty-some year; but even before the Silver Crash of 1893, an outmigration to Capitol Hill was well underway. Drawn by the allure of its social prestige, many of those who could afford to move to the newer, more fashionable neighborhood. There were, of course, those among the prominent and prosperous who remained in their houses in the old neighborhood until their deaths. But even as they stayed put, the neighborhood began to change, to undergo that transformation that would allow it to survive, to serve new purposes, new migrations of people.

By the teens and twenties of the new century, Latino and African American families were increasingly moving into the district. Welton Street emerged as a cultural hub for Black communities, who defied the efforts of racially restrictive housing covenants to erase opportunities to thrive, both socially and economically, in Denver. As part of the greater Five Points neighborhood, Curtis Park was shifting from an economically diverse neighborhood to an ethnically diverse one. By this time, many of the houses of Curtis Park - perhaps most of them - had been divided up into small living units. What had been intended as single-family dwellings became boardinghouses where one rented a room or two, shared a bathroom down the hall, and perhaps a common eating area. The population of the neighborhood continued to reflect the same ethnic mix that first settled in the area, but it was now lower-middle-class, blue-collar, in makeup.

By the 1940s, as the older population began to leave the neighborhood, Mexican Americans started to move in, originally to rent, then to buy up, the houses of Curtis Park, now a half-century old. The changing ethnic mix is nicely illustrated by the story of the Glover family, who owned the house at 2663 Curtis in the 1930s and 1940s, and their foster sons, P.S. and Tony Arroyo, children of Mexican parentage. When the boys were orphaned, Mr. and Mrs. Glover took in the Arroyo brothers and raised them in their home on Curtis Street. P.S. Arroyo eventually married the daughter of the Glovers and subsequently inherited the Curtis Street house from her parents. His brother, Tony, bought the house two doors down, at 2639 Curtis. Both brothers continued to live in their Curtis Street homes until their recent deaths, by which time they had become prominent members of a now largely Hispanic community.

After the outbreak of World War II, large numbers of Japanese Americans also came to live in Curtis Park. There were already some Americans of Japanese descent in the area before the war, as witnessed the presence of a Japanese Methodist church in the house at 2801 Curtis in 1919, which subsequently bought the church building at 2501 California in 1935. The pastor of that church, the Reverend Seijiro Uemura, is credited with helping persuade Colorado Governor Ralph Carr to invite Japanese Americans who had been forced into relocation centers to take refuge in Colorado. When Governor Carr agreed to welcome the West Coast evacuees, thousands came, primarily in 1942 and 1943, many of whom settled in Curtis Park. Most of those who had taken up residence in the neighborhood under difficult circumstances left it as soon as they could afford to do so. By the 1970s only a few Japanese Americans still remained.

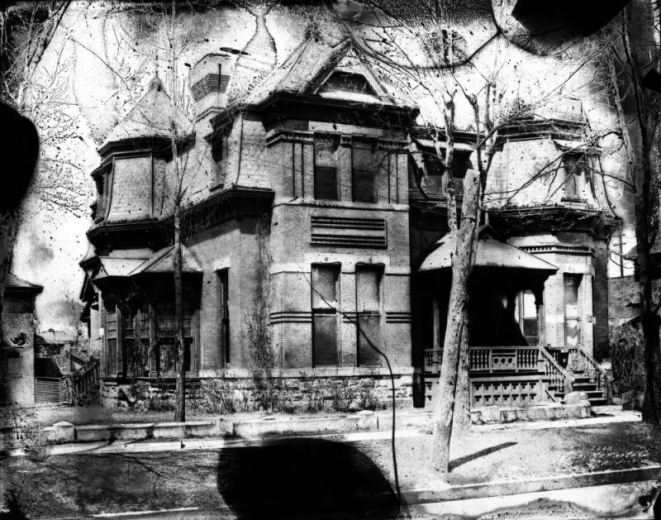

Despite the stability brought to the neighborhood by both Mexican-American and Japanese-American residents, Curtis Park was clearly in decline by the 1960s and 1970s. A number of the houses were in disrepair, others were boarded up. Sandra Dallas, in her 1971 book, Cherry Creek Gothic, said of the area that it lay in "a semislum trance" waiting to be torn down or discovered and saved. A number of houses had, in fact, already been demolished, replaced only by the vacant lots where they had once stood. Again, many who could do so left the area, wanting to put behind them the stigma of living in a run-down, inner-city neighborhood.

One day in 1975, Josie Cosio, born and raised in Curtis Park, was talking to her brother near the corner of Curtis and 29th Street when he looked over and saw people at the abandoned house across the way. He expressed surprise and asked Josie what in the world they were doing over there. When she told him they had bought the house and were moving in, he said in disbelief that Curtis Park was a neighborhood you moved out of, not into. By that time, he had himself moved away, but Josie has stayed to be among those who have held out a welcoming hand to newcomers to the neighborhood.

For there were newcomers. Fortunately, the old houses of Curtis Park, however, faded and bedraggled, hadn't lost their ability to charm and attract yet another group of new residents who could look beyond the abandonment and disrepair that had come to characterize the neighborhood to see what gems Curtis Park still contained. In 1975 a good portion of the neighborhood received a district designation on the National Register of Historic Places, calling attention to the incredible fact that nearly 500 houses from the late nineteenth century were still standing in the shadow of downtown Denver. Since that time, slowly but not surely, the decline of the neighborhood, which might well have proved terminal, has been stemmed. A new migration into Curtis Park has begun, prompted this time, in the first place, by a love of its great old houses, and then by the diversity of the life within it, a diversity to match that of the architectural treasures it contains. For Curtis Park remains what it has always been: a neighborhood of peoples from different places, and different backgrounds, who have tacitly agreed to at least tolerate, at best enjoy, the complexity of their rich communal life.

Introduction and following entries from Curtis Park, Denver's Oldest Neighborhood by William Allen West, 2002. It should be noted that the Auraria neighborhood is considered Denver's oldest neighborhood, which predates the city's establishment. Please see the Auraria Neighborhood Guide.

(As of 2015, it is reported that most of the structures in Curtis Park have been designated as historic, thanks to the efforts of the Curtis Park Neighborhood Association. This author also learned that at one time, the entire area of Curtis Park was considered part of Five Points, but that as gentrification took hold, the "Curtis Park" distinction was strengthened because of the negative associations some people had with Five Points in those days.)

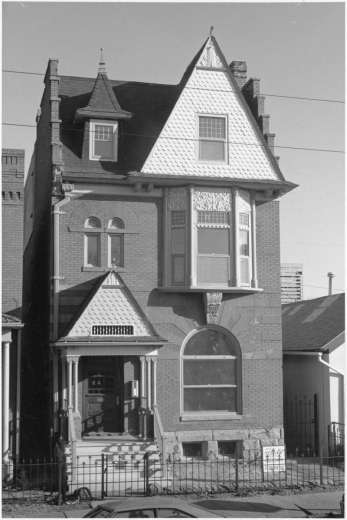

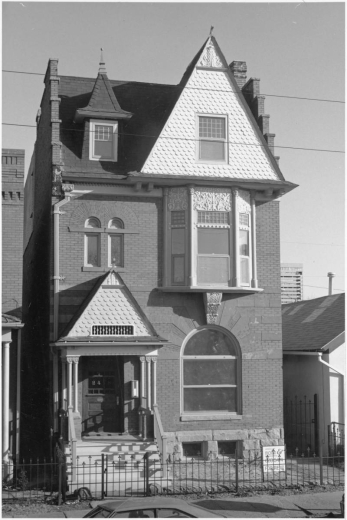

Remarkable for its wide-ranging eclecticism, this architectural tour de force was considered by Richard Brettell, in his book Historic Denver, a virtuoso piece by a well-known architect of his time. Stone coursework radiates out from the first-floor window, above which an elaborate oriel window rests on massive sandstone support. The steep roofline is flanked by stepped walls in the Dutch fashion.

Lydon, who worked for the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad, lived in his fabulous house for only twelve years. In 1903, he moved on to Capitol Hill.

The eclectic-style house was built in 1891 at a cost of $8,000 by architect John J. Huddart.

The original front part of this house was built to house Calvary Baptist Church until the church building could be erected. When the congregation first used it for services, it was in such an unfinished condition that it was described as being only somewhat better than a tent. The church proper was erected in 1887 behind the house, facing 27th Street, at which time the house became a parsonage. Ironically, it has long outlasted the church it was intended to serve.

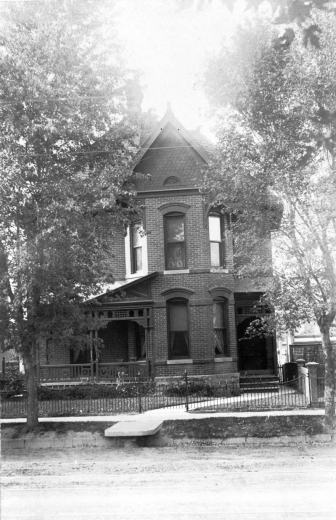

Originally a modest one-floor house, the Kramer House was subsequently greatly enlarged and completely remodeled. At that time it was given its distinctive mansard roof. Signs of the remodeling that were once hidden behind a long-vanished front porch are now apparent in the brickwork next to the large first-floor window on the left side of the facade. Its first floor was completely gutted, the house stood empty for many years until rescued by its current owner from long neglect. From 1883 to 1890 the house was occupied by Walter Kramer, vice president and manager of the Rio Grande Western Railroad.

The Second Empire-style house was built in 1879, at a cost of $1,675, by an unknown architect.

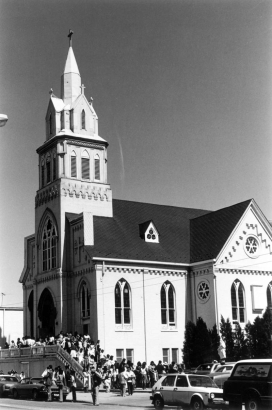

Though there were once several churches in Curtis Park, this is the only survivor. Built for the First German Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church, it served as the Japanese Methodist Church from 1935 to 1963. The house next door, at 2515 California, was built as the parsonage for the church. The building was constructed in 1887 by an unknown architect.

This house at 2619 California Street shares its history with the one next door at 2627 Champa. It, too, was almost certainly moved to its present site from an original downtown location. Unlike the Ford House, however, this one still retains the brick veneering and the fish-scale shingling it received in an early remodeling. The vernacular-style building was built at an unknown date, by an unknown architect.

Built to the designs of W. J. Edbrooke, whose most illustrious building was the sadly demolished Tabor Opera House, this was the second Temple Emanuel on Curtis Street. When it was built, a number of German Jews lived in the Curtis Park area who constituted the synagogue's original congregation. After a fire in 1897, which nearly destroyed the building, the decision was made to erect a new synagogue at Pearl and 16th. In 1902 this one was repaired under the direction of Frank Edbrooke, the now more famous brother of the original architect, making the building probably the only one created by two Edbrookes. The rebuilt structure first served the BMH congregation, then that of Beth Joseph.

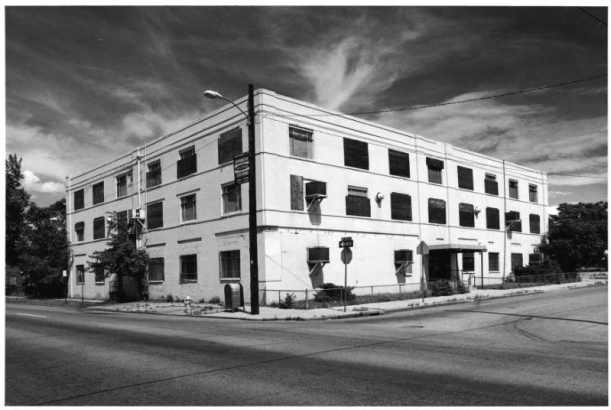

Now reduced to serving as a warehouse, many of its exterior and interior features erased, little remains to call attention to the building except its massive solidity, reinforced by buttresses against the exterior side walls. Currently surrounded by land uses that have adversely affected its potential for adaptive reuse, it still awaits a chance for a new life.

The Italianate / Moorish structure was originally built in 1882, and then rebuilt in 1902, at costs of $9,000 and $7,000, by architects W. J. and Frank Edbrooke.

The slogan of the Ideal Laundry was "We Use Artesian Water." Immense storage tanks under the floors of the building could hold over 800,000 gallons of water, pumped from the company's own artesian wells on-site. In 1928 the Ideal became the first laundry in the country to announce that it would use Lux soap exclusively in its washes. At the height of its operation, it used 1,000 pounds of Lux a week.

Though the main entrance to the building was moved during a recent remodeling, the original terra-cotta doorway remains the most interesting part of the structure, which occupies a site where once ten houses stood. The building now serves as headquarters for Denver's Child Opportunity Program and related social services.

The Early Modern Industrial style structure was built in 1910 (with additions in 1916, 1918, 1920, and 1929) and was designed by an unknown architect and constructed for an unknown cost.

Since serving the purposes of the National Guard, this building has had a number of uses. Among other things, it has been a dance hall and a boxing venue.

The Eclectic style building was designed by architect William Quayle and built in 1889 at a cost of $20,000.

Curtis Park has several pairs of twin houses, though none more elaborately decorated than this delightful pair at the downtown fringe of the neighborhood. The carved capstones above their windows are especially noteworthy. Unfortunately, their location makes their future chancy. All the houses between Park Avenue West (old 23rd Street) and 27th Street are located in a B-8 zone, a wide-open, permissive zone district that has encouraged usages incompatible with the historic residential character of Curtis Park.

Orlando Scobey, who was very active in early Denver real estate, lived here from 1885 to 1891 before moving to Capitol Hill. The house then became the home of Irish-born John Cook, who also prospered as a realtor. With its two-story front bay, original porches, and swag iron fence, the house remains a beauty.

The Eclectic style home was built around 1886, by an unknown architect for an unknown price.

One of Curtis Park's rare, early wooden houses, this home was built in the mid-1870s, by (probably) David C. Crowell, who listed himself in the Denver City Directory as a carpenter and engineer. The pediments above the front windows are re-creations but are of the same size and shape as the original pediments, as indicated by surviving outlines discovered in the course of the restoration of the house.

Originally a one-story house occupied by Theodore and Amadee Firbourg, this home was turned into a textbook Queen Anne in 1891 when the Baerresen Brothers added the second floor and made other alterations for Jacob Boehm, by then its owner. Its two-story porch, rising to a gable within the larger main gable, creates an elaborate facade.

The house was built between 1885 and 1891 - the second-floor addition was designed and executed by the Baerreson Brothers for a cost of $2,500.

This home is a classic assemblage of high Victorian architectural elements. The bay, balanced by the front porch, projects out beneath the slanting rooflines of the second half-story, creating a complex set of relationships. Although many Curtis Park houses once had decorative iron cresting, most of it has been lost over time. The cresting above the front bay here is an original and distinctive feature of the house.

Orlando Scobey lived here for a year before moving down the street to 2543. He probably built both houses.

(In this photo, William Allen West, Curtis Park historian, is posing by the porch.)

This Italianate was one of the many houses in Curtis Park to benefit from Historic Denver's FACE Block Rehabilitation Program. In the period 1978-1982, the program financed the exterior restoration of forty-three houses of low-income homeowners who would not otherwise have been able to afford such work.

This house was built around 1885, by an unknown architect for an unknown cost.

Originally built as the home of Irving Manatt, a grocer, by the 1970s this splendid house had been standing empty and derelict for years. When the first of its saviors purchased it in 1975 for $10,000, the house had been stripped bare. It had a see-through hole in the roof, but neither a furnace in the basement nor a handrail for the staircase to the second floor. The house has come a long way since then.

This Italianate style house was built around 1882, by an unknown architect for an unknown price.

This was the home of Louis and Louise Anfenger, both born in Germany. Having immigrated to the United States as young people, they met and married in the East, then came to Denver. Anfenger engaged in various enterprises, including real estate, banking, and insurance, becoming prosperous in the process. He was also active in politics and was elected to serve in the state legislature. Anfenger was instrumental in forming the Temple Emanuel Synagogue at Curtis and 24th, as well as the National Jewish Hospital. He died here in 1900, only fifty-eight years old. His family stayed in the house for another five years.

By the 1970s the house had fallen on hard times indeed. Its rooms were painted black, it had become home to drug use, voodoo rites, and prostitution. After a police crackdown, the house changed hands but not fortunes. With its original plate-glass windows smashed and boarded up, its new owner offered it as a house of horrors, charging admission to those looking for cheap thrills in a reputedly bad neighborhood. When a few of those struggling to win for Curtis Park had a more favorable notice than it was accustomed to complained to the owner about her enterprise in the Anfenger House, she responded that if they closed her down, she would simply have the building demolished.

Luckily, beginning in the late 1970s, the house again came into the hands of a series of people who have cared for it, rescuing it from ignominy and restoring it to its proud place on the corner of 29th and Champa.

The Italianate-style home was built in 1884 by an unknown architect at an unknown cost.

Born in Vermont, Joslin came to Denver in 1872 and the following year opened his first department store at 15th and Larimer. He sold his interest in the Joslin Dry Goods Company in 1915 but remained as president until his death in 1926 at the age of ninety-six. Joslin was noted in his own time for his love of music and horses. When he died in his Champa Street home, where he'd lived for forty-six years, the Rocky Mountain News called him "the grand old man of Denver business."

The Italianate-style home was built in 1880, by an unknown architect and at an unknown price.

Originally, this Queen Anne was the home of Leonard Walters, an early dealer in Colorado livestock. The surround for the two windows high in the front gable of the house provides a massive sculptural climax at the top of the facade. Like many other corner houses in Curtis Park, this one has two decorative porches.

This home was built in 1888 by architect F. C. Eberly, at a cost of $7,500.

Patrick Ford, born in Ireland in 1847, moved to Denver from St. Louis where he worked as a foreman on the construction of the famous Eads bridge. In Denver, he built the city's first waterworks and was active in the construction of railroads throughout the state. In 1885 he moved this house, and probably the one next door at 2619 Champa, from their location in what is now downtown Denver to their present site. His daughter, Josephine Ford Brauch, who was born in the house and lived in it until her death in 1984, remembered that it was moved from the corner of Champa and 15th where some of Denver's earliest houses had been built in the 1860s. If this house and the one next door do indeed date from the time before the railroads reached Denver, they may well be the oldest residences still standing in the city. Both were built as wooden structures, subsequently brick-veneered and treated to shingling on their second stories. Recent remodelings of the Ford House have taken it back to an earlier look. Patrick Ford died in his Champa home in 1918. Mrs. Ford celebrated her ninetieth birthday here in 1934.

The vernacular-style home was built at an unknown date, by an unknown architect.

This magnificent high Victorian house was originally built for James F. Mathews, an ore and bullion broker. He and his wife were socially prominent members of early Denver society. In 1890, Isaac Gotthelf bought the house for $25,000, at the time a very considerable sum. Having immigrated from Germany with only $5 in his pocket, Gotthelf made his fortune as a merchant at Saguache, in the upper San Luis Valley, though he had cattle and banking interests as well. He was twice elected to Colorado's House of Representatives. Gotthelf bought the Champa Street house so his four children could receive their education in Denver. Mrs. Gotthelf, niece of the director of the U.S. Mint in Denver, lived in the house with her children while her husband came and went. He died here in 1910. In 1912, Gordon, the youngest of the Gotthelf children, was married in the house. His bride remembered it as an elegant home with a staff of servants. In 1915, Mrs. Gotthelf moved back to Saguache, ending the family's residence on Champa Street.

Fritz Thies lived here until his death in 1921 at the age of seventy-one. He conducted a wholesale liquor business with his partner, next-door neighbor Sam Rose, the largest concern of its kind in the region. He was also a musician who gathered other musicians for private concerts at his home. An obituary described him as a "pioneer Denver business man, banker and music master." His granddaughter, Mrs. Stanley Wallbank, remembered her grandfather's house, where the family gathered for lengthy Sunday dinners, as being full of music. Across the top of his grave marker in Fairmount Cemetery, a musical passage has been carved in the granite, doubtless one loved by Fritz Thies and probably often heard within the house when he was alive.

The twin to the Thies house stands next door. Superb examples of the Italianate style at its stateliest, they represent the kind of homes that were built on Champa Street in the late 1870s and early 1880s along the route of Denver's first horse-drawn streetcar line.

The Italianate-style home was built in 1880 at a cost of $11,500, by architect F. C. Eberly.

By the 1970s this pressed-brick building was abandoned, boarded up, and burned. As a final indignity, vandals pried off most of the characteristic terra-cotta ornamentation that architect Robert Roeschlaub liked to use. Luckily the building was eventually rescued and given a new lease on life.

The Romanesque Revival style building was constructed in 1890 at a cost of $14,000, and designed by architect Robert Roeschlaub.

Many of the photographs in this exhibit have "FACE Block Project" in their title, and in fact, if you search our database here, we have a number of photographs and other resources pertaining to Historic Denver's FACE Block Rehabilitation Program, a 1981-82 urban renewal initiative. Here is an overview of the project from the June 1980 Historic Denver News:

Historic Denver Awarded $100,000 for Curtis Park Project.

“The Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service of the Department of the Interior awarded Historic Denver money to begin restoration work in the Curtis Park neighborhood.”

Many of the homes of Curtis Park were constructed between 1885 -1890, making it one of Denver’s oldest neighborhoods. The residents of Denver’s pioneer streetcar “suburb” built the Italianate, Queen Anne, Gothic, and other Victorian-style homes that, by the early 1980s, had suffered from neglect. Preservation proponent, educator and Curtis Park resident since 1976, Bill West recalls an early visit to the neighborhood by then, Colorado First Lady, Anne Love: “She was clearly alarmed.” He says. “This was a rough neighborhood in those days.” Historic Denver’s involvement began in the late 1970s with the relocating of three threatened Curtis Park houses.

The 1981-82 Face Block Project funded by the Department of Interior (spearheaded by HD Director Barbara Sudler and Board President Jim Bull) revitalized the historic neighborhood monumentally. “It involved a massive number of houses – 50 or 60.” recalls West. “Most were owned by people of a certain economic level who could not otherwise afford to fix these places up. In the neighborhood, it helped erase the visual distinction between the “haves” and the “have-nots.”

By reinstalling sandstone sidewalks, lining the streets with trees and rejuvenating the city’s first park, as well as restoring the street façades of the houses, there is no doubt that Historic Denver's early involvement in Curtis Park spurred a renewed sense of neighborhood pride that inspired a core grassroots group of preservation activists, many of whom remain in the neighborhood to this day.

Explore photos of Curtis Park in our gallery below, or in our digital collections.