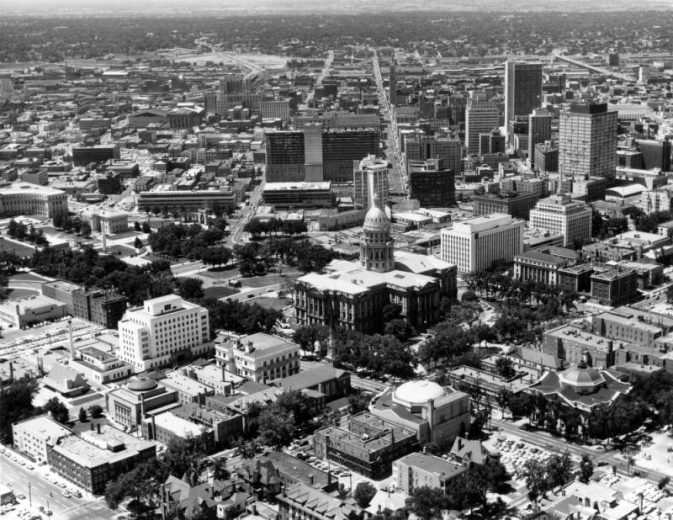

The mile high locale of the Colorado State Capitol was once the neighborhood of Denver’s wealthiest residents. By the close of the twentieth century, the area had evolved into an exciting blend of past and present with classic century-old mansions and contemporary town homes and apartment buildings existing side by side. From the historic Molly Brown house to the boldly contemporary Art Museum Residences, Capitol Hill is an exuberant residential, governmental and commercial center with an array of museums, cafes, clubs, galleries, coffeehouses and shops.

The history of the Capitol Hill neighborhood encompasses the history of a neighborhood as well as the location of Colorado’s most important structure, the State Capitol. For 150 years Capitol Hill has played an important role in the history of the Centennial State.

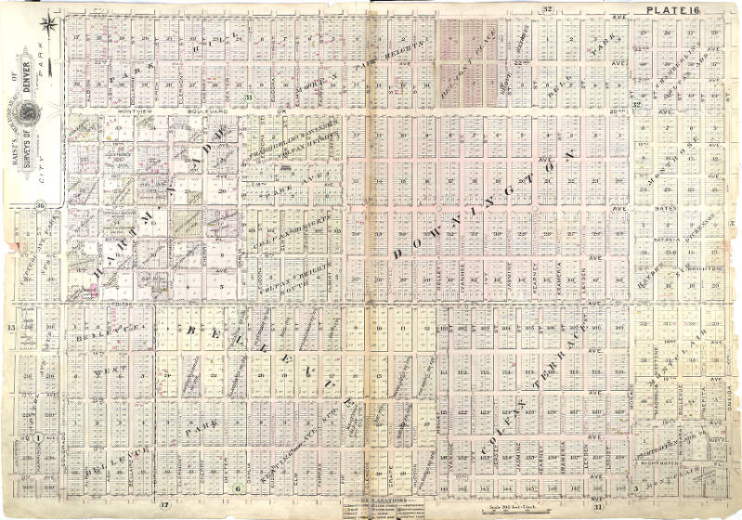

Gold seekers founded Denver City in November 1858, but it wouldn’t be until 1867 that the Queen City of the Plains would beat out Golden and be officially designated the territorial capital. That fall, Governor Alexander Hunt sent out a call for land for a capitol building site. Several persons donated land, including former territorial governor John Evans, who donated a parcel of land in the Evans Addition (today known as the Golden Triangle) to try to bring higher property values to his development. It would be Henry Brown, though, whose land would finally be accepted by Hunt’s Capitol Commission. Initially, many dismissed “Brown’s Bluff,” as the site came to be known, as too far from the center of town. By 1876, Colorado would gain statehood, but still nothing had been built on Brown’s land. Disgusted, he tried unsuccessfully to get the land back three years later. Yet throughout the decade since Brown’s donation, Denver had continued to expand eastward, as people started to move to the area around Brown’s Bluff even before the State began construction of the Capitol in 1886.

Today, the Capitol with its famous gold dome proudly stands high above downtown Denver and the thriving neighborhood that grew up around it, Capitol Hill. More than just the place where laws are made, Colorado’s capitol building is a celebration of the state’s history, with innumerable artworks and artifacts that tell the story of the Centennial State.

At the time of the Capitol’s construction, wealthy Denverites decided that Capitol Hill was the place to be. Denver’s earliest houses were clustered around Cherry Creek and Auraria. In the 1870s, after Governor John Evans built a house at 14th and Arapahoe, wealthy Denverites followed suit, building a Millionaire’s Row of impressive Italianate and Second Empire houses along 14th. It wouldn’t be long, however, until the downtown that had started around today’s LoDo began creeping eastward. Finding their fancy residential enclave being overcome by commercial buildings, Denver’s wealthy needed a new Millionaire’s Row. When wealthy banker Charles Kountze and railroad financier David Moffat sold their 14th Street mansions for new Queen Annes on Capitol Hill, many of their neighbors followed. John Wesley Smith, an early Capitol Hill landowner, oversaw construction of a City Ditch that would bring water to the neighborhood, leading to lush lawns, trees, and parks. In the 1880s and 1890s, anybody who was anybody sported an address on Lincoln, Grant, Sherman, Logan, Pennsylvania or Colfax.

As transportation developed, Denver’s wealthy no longer needed to live within walking distance of downtown. Now, instead, a greater distance from downtown became a sign of prestige, signifying you had enough money to drive to work from a location far from the smoke and grime of the city. Colfax was zoned for commercial use in the 1920s, and the old mansions were increasingly converted to offices and apartments before being demolished to build larger apartment structures, office buildings, and parking lots. Today’s residents living nearest the Capitol dwell in apartments and condos instead of mansions. However, the remaining old houses give Capitol Hill a special charm. After urban renewal in the 1950s and 1960s gutted much of Denver’s finest architecture, some residents began to lament this destruction. The 1970s, though still rife with demolitions, saw the emergence of groups like Historic Denver, Inc., which worked to preserve Denver’s historic buildings, and the Denver Landmark Commission, which began nominating structures as individual landmarks and designating areas retaining many contributing historic structures as Landmark Districts. Today, Denver boasts more Landmark Districts than any other city in the nation, and many of these celebrate the architecture of Capitol Hill.

Capitol Hill’s historic architectural treasures include more than just houses. Capitol Hill’s numerous schools, hospitals, and places of worship also illustrate a strong sense of community.

Before a school was built on Capitol Hill, area children attended the Broadway School just outside Capitol Hill at 13th and Broadway. Soon, however, the Emerson School at 14th and Ogden would be built, followed by the Corona (now Dora Moore) School at 9th and Corona. Private academies also catered to the area’s wealthy.

Capitol Hill has several hospitals along its northern edge, and also has had around two-dozen churches and synagogues. Although a few of these have been demolished and others given new uses, most still operate as first intended. Given their urban location, Capitol Hill churches especially cater to the poor, offering food and shelter to the area’s needy.

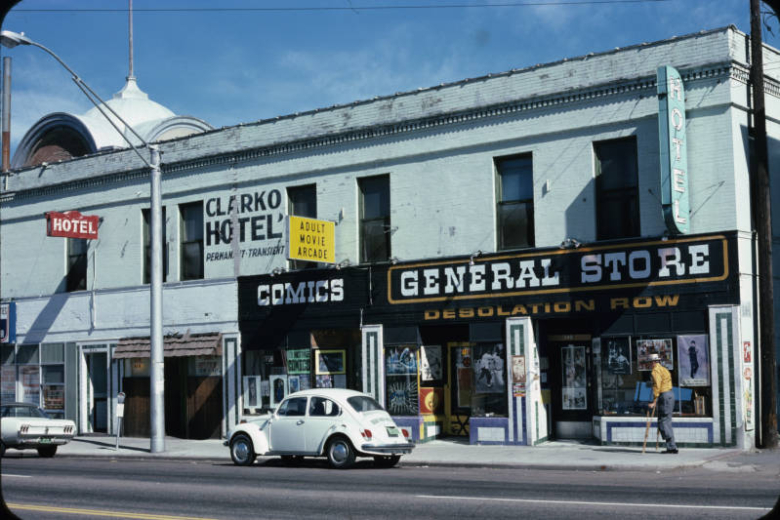

East Colfax Avenue is the heart of Capitol Hill. Today the neighborhood’s main commercial drag, East Colfax actually started out as an exclusive residential avenue. It was named for Schuyler Colfax, an Indiana congressman who served as Speaker of the House and later as Vice President under Ulysses S. Grant. When Colfax visited Denver in 1865, the town named their avenue Colfax to flatter the politician into supporting Colorado’s bid for statehood.

Colfax Avenue bisects the Capitol Hill neighborhood, but runs far beyond the Hill’s borders on either side. East Colfax starts at Broadway and continues into Aurora, while West Colfax, the portion west of Broadway, stretches out to Golden. Colfax is said to be America’s longest continuous street; the New York Times has also called it America’s wickedest. From its early days as a mansion district, East Colfax evolved into a busy street lined with stores, apartments, and bars. By the 1960s, some internationally known performers like Bob Dylan, Judy Collins, and the Smothers Brothers got their start performing in Colfax joints like the Satire Lounge. Less reputable establishments, such as adult book and video stores and strip joints, like Sid King’s famous Crazy Horse Bar, started opening up on the avenue. Soon East Colfax would also gain a reputation for prostitution. Motels were used more by the hour than by the night. Fights, drug dealing, and other seedy activity became commonplace. East Colfax’s Number 15 bus became the most notorious bus route in town.

In recent years, the City of Denver has worked to clean up Colfax. New luxury high-rises and a resurgence of interest in fixing up old homes has changed the avenue, as has a new main street zoning ordinance which calls for the beautification through such improvements as street trees, and not allowing parking lots in front of any new buildings. Some City Council members and neighborhood activists are even working to bring back a trolley system along Colfax. Such improvements have cleaned up the area, but it still retains its own Colfax character.

With its rich diversity of people and places, Capitol Hill offers something for everyone. In addition to houses and institutions, Capitol Hill has a large commercial presence, not just on Colfax but also along 6th Avenue and the numbered avenues north of 11th. Over the years Capitol Hill has been home to many fraternal organizations that have enlivened the city. Theaters, art galleries, and some of Denver’s finest restaurants bring culture to the area. Capitol Hill’s strong neighborhood association, Capitol Hill United Neighborhoods (CHUN), has contributed to the improvement of Capitol Hill through historic preservation efforts, zoning and liquor license issues, tree planting, and the annual Capitol Hill People’s Fair.

Since its founding, Capitol Hill has always been home to a wide variety of people. Even in its earliest years, the city’s demimonde were not the only ones to make Capitol Hill their home. As the neighborhood grew, so did the types of housing, and the types of people. A number of nationally known celebrities, past and present, have had associations with Capitol Hill, while the greats who fashioned Denver often had Capitol Hill addresses. Yet many ordinary people lived in the area too. It has continued to be a patchwork quilt of people and places, sights and sounds, history and culture. Some parts are wicked, some parts are wealthy. Yet everywhere on Capitol Hill there is a story to be told.

by Amy Zimmer

One of the oldest sections of Denver, the Capitol Hill neighborhood is located in central Denver. This neighborhood contains many historical and civic buildings, most important of which is the Capitol Building of Colorado. Essentially forming a square shape, the boundaries of Capitol Hill are Colfax Avenue on the north, to Downing Street on the east, to 7th Avenue on the south, and Broadway on the west.

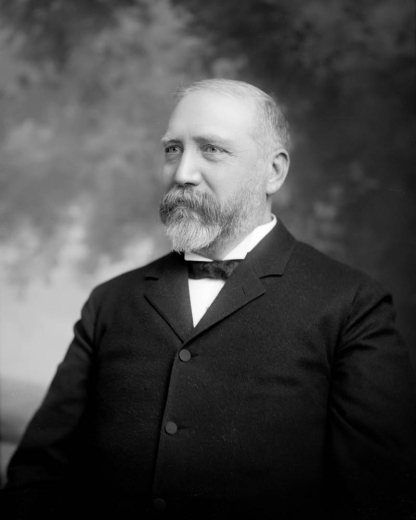

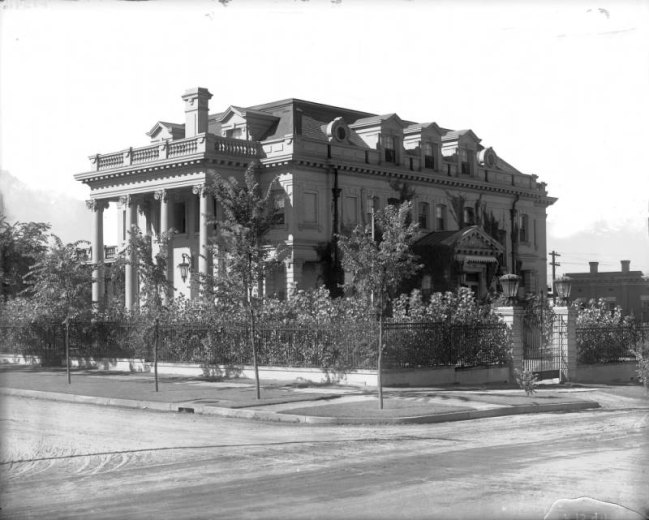

Dennis Sheedy made his fortune in banking, cattle, retail and mining. He was the president of the Globe Smelting and Refining Company, vice-president of the Colorado National Bank and president of the Denver Dry Goods Company. He lived in a magnificent mansion at 1115 Grant Street in the heart of the Capitol Hill neighborhood.

Dennis Sheedy was born in Ireland on September 26, 1846. His parents were John and Margaret (Fitzpatrick) Sheedy. John Sheedy, a farmer, moved his family to the United States and settled first in Massachusetts and then Iowa. After John Sheedy’s death, Dennis was in charge of supporting the family, going to school during the winter months and working as a clerk in a general store. In 1863 when only seventeen years old, Dennis Sheedy came to Denver and worked as a store clerk. Shortly afterward, he moved to the Montana Territory and worked in mining and merchandising. He returned to the West in 1866 when he was commissioned in the Army as a captain to manage the travel of emigrants and supplies from the Missouri River to Utah and Montana. In 1868, he became a grocer in Helena, Montana and begun to build his business in the cattle industry. He located his cattle business in Kansas City from 1871 to 1881 and conducted business throughout the western territories. After his investments in cattle and mining made him rich, Dennis returned to Denver in 1881 to settle down permanently.

Back in Denver, he bought stock in the Colorado National Bank and was elected vice-president. He remained in that position until his death in 1923. He became involved in the treatment and smelting ore industry and served as the president of the Globe Smelting and Refining Company, which established the Globeville neighborhood in North Denver. Under his leadership, the smelting plant became the largest in the country and increased its capacity more than ten times. After the McNamara Dry Goods Company went bankrupt during the Silver Panic of 1893, Dennis became involved once again in merchandising and eventually was named the president of the re-organized Denver Dry Goods Company in 1894. Due to its success, the store later built a six-story building on the corner of California and Fifteenth Street in downtown Denver that was designed by architect Frank Edbrooke.

Dennis Sheedy married Katherine Vincentia Ryan, daughter of Matthew Ryan, a wealthy businessman of Leavenworth, Kansas on February 15, 1882. The couple had six children but only two daughters lived beyond infancy, Marie Josephine and Florence Elizabeth. Katherine passed away on June 22, 1895. Dennis married Mary Teresa Burke of Chicago and niece of Bishop Maurice F. Burke of St. Joseph, Missouri on November 24, 1898. They had two sons but both died in childhood.

The Sheedy Mansion with carriage house at 1115 Grant Street began construction in 1890 and was completed in 1892. The Mansion is a good example of late Victorian Era eccentricities by combining elements from Queen Anne and Richardsonian Romanesque architecture styles and details. The architects were Erasmus Theodore Carr and William Pratt Feth, from Kansas. The Sheedy Mansion is the only known Colorado commission from either architect.

Dennis was a member of the Denver Club, the Denver Athletic Club, the Denver Country Club, the Knights of Columbus and a member of the parish of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Denver. At the age of 77 on October 16, 1923, Dennis Sheedy passed away at his home. He had been suffering from a cold that turned into pneumonia.

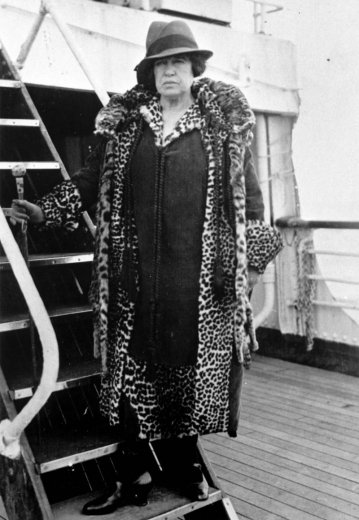

Margaret (nicknamed Maggie) Tobin Brown was born July 18, 1867 in Hannibal, Missouri to John and Johanna Tobin. John Tobin worked for the Hannibal Gas Works. Margaret’s siblings were Daniel, Helen and William. She had two older half-sisters, Catherine and Mary Ann.

In 1883, Margaret Brown's half sister, Mary Ann, and her husband, Jack Landrigan, moved to Leadville, Colorado. Margaret and her brother, Daniel, followed three years later. Daniel worked as a miner and Margaret found a job in a dry goods store, Daniels, Fisher and Smith. In Leadville, she met James Joseph Brown (J.J.) who, like Margaret, was Irish Catholic. They married on September 1, 1886. J.J. Brown was thirty-one years old and Margaret nineteen. On August 30, 1887 their first child, Lawrence Palmer, was born. Their second child, Catherine Ellen, known as Helen, was born in 1889.

In 1891, a group of Leadville mining men including John F. Campion formed the Ibex Mining Company. By 1892, J.J. Brown had acquired enough stock in Ibex to sit on the board of directors. The price of silver fell and by 1893 most of the miners were unemployed. As the price of silver fell, the price of gold climbed and despite bad economic conditions Ibex made another attempt at mining the Little Johnny Mine, this time for gold. Reported to be the world’s richest gold strike, the mine’s owners quickly became wealthy.

In 1894, Margaret and J.J. Brown moved to Denver and bought a home at 1340 Pennsylvania Avenue (now Pennsylvania Street) in the Capitol Hill neighborhood. The Browns, regularly listed in the city’s social directory, were excluded by Denver’s wealthy elite, the “Sacred Thirty-Six.” Margaret Brown became a charter member of the Denver’s Woman Club and an associate member of the Denver Women’s Press Club. Catholic charities were of particular interest and she and J.J. Brown gave generously to St. Vincent’s Orphanage in Leadville. In Denver, she raised money for St. Joseph Hospital and the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception. She worked with Judge Benjamin B. Lindsey of Denver’s Juvenile Court and became a sponsor of the western branch of the Alliance Francais.

Margaret and J.J. Brown separated in 1909 after nearly 23 years of marriage. Due to strong Catholic beliefs they never divorced. J.J. Brown died September 5, 1922.

While traveling in Europe in 1912, Margaret Brown received news that her grandson, Lawrence Palmer Jr. was ill. She booked first class passage on the Titanic. On the evening of April 14, the ship struck an iceberg and Margaret Brown found herself in a lifeboat struggling to survive. She took charge of the lifeboat and kept the other passengers hope of rescue alive with her invincible spirit until the Carpathia arrived to save them. Once on board the Carpathia, Margaret Brown helped organize rescue efforts. Her knowledge of foreign languages enabled her to help the immigrant passengers. Margaret Brown composed lists of survivors and arranged for this information to be radioed to their families. Together with a committee of other wealthy survivors, Margaret Brown helped raised money for the destitute victims. By the time the ship reached New York, nearly $10,000 was pledged.

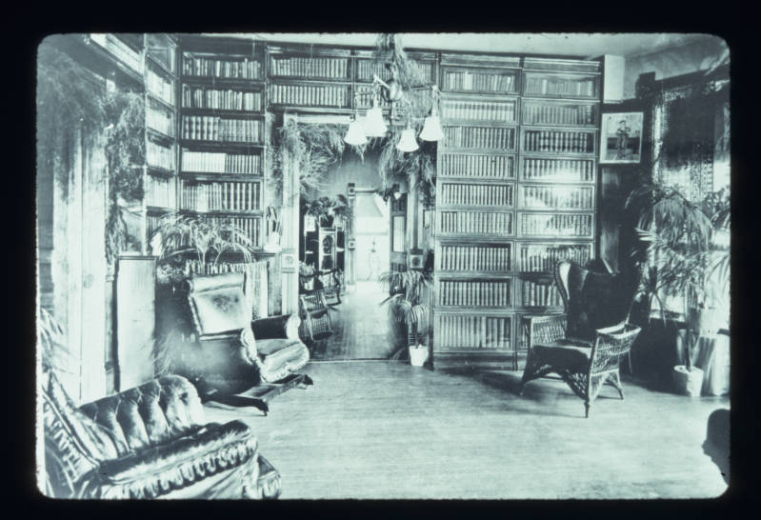

In 1927, Margaret Brown became involved with one of Denver’s first historic preservation projects. When she learned that the home of poet Eugene Field was in danger of demolition she purchased it and donated it to the city. Relocated to Denver’s Washington Park, Field’s home served as a library for forty years. Ironically her house on Pennsylvania Street was also planned to be demolished in the 1960’s until Historic Denver, Inc. stepped in and saved the building. The Molly Brown House has been restored and turned into a museum. Today it is one of the top tourist destinations in Denver.

Many stories surround the legendary “Unsinkable Molly Brown” so that separating the truth from fiction is a difficult task. Some say that upon reaching New York, Margaret Brown told reporters “I had typical Brown luck. I’m unsinkable.” After that she was known as the Unsinkable Mrs. Brown. Kristen Iverson in her book, Molly Brown: Unraveling the Myth, disagrees and claims the nickname ostensibly started with Polly Pry, a local gossip columnist.

Caroline Bancroft in The Unsinkable Mrs. Brown alleges Margaret Brown thought her own nickname Maggie wasn’t elegant enough and encouraged people to call her Molly or Peggy, but most sources state that Margaret Brown wasn’t called Molly in her lifetime. Richard Morris who wrote the musical, The Unsinkable Molly Brown, chose the name because he felt it was easier to sing.

Margaret Tobin Brown died October 25, 1932, in the New York Barbizon Hotel at the age of sixty-five.

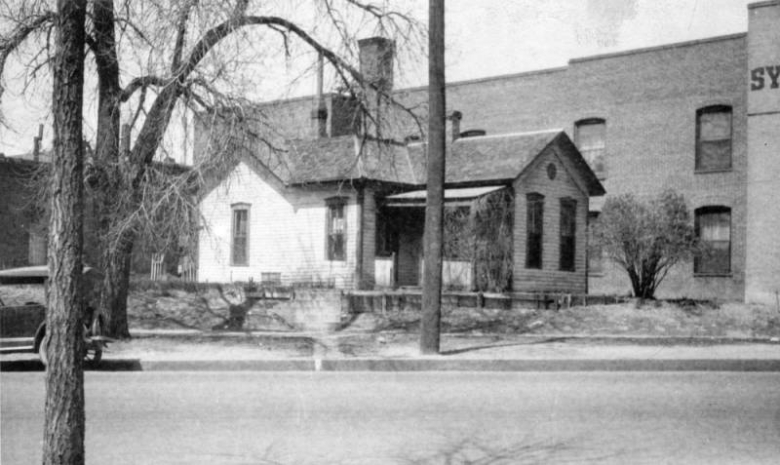

This house was built in 1889 for Isaac and Mary Large, who sold it to J. J. Brown in 1893 or 1894 for $30,000. Brown had worked his way west through jobs in various mining camps. As a superintendent for the Ibex Mining Company in Leadville (owned by John F. Campion), he oversaw the Little Jonny Mine, which in 1894 produced one of the widest veins of gold and high-grade copper ore ever found. J. J. and his wife, Margaret “Molly” Tobin Brown, moved into the house in April 1894. Because of J. J.’s subsequent ill health, the result of his many years spent in the mines, the deed was transferred into Molly’s name in 1902. Molly, who achieved international recognition as the heroine of the 1912 Titanic disaster, owned the home until her death in 1932, after which the house and its contents were sold at auction. Following a succession of five owners over the next forty years, Historic Denver bought the house in 1970 for $80,000 and opened it as a museum. Since then, Historic Denver has spent approximately $1 million on its restoration.

The work of prominent Denver architect William Lang is characterized by an eclectic mix of architectural styles, apparent in this combination of a Queen Anne structure with Romanesque Revival touches such as rusticated stonework and arches. Lang’s exuberant style is continued throughout the house with four decorative fireplaces, three stained-glass windows, a painted conservatory ceiling in the dining room, and a combination of golden oak, cherry, and mahogany woodwork on the first floor.

It is unknown where Lang was trained, but between 1888 and 1893 he designed more than 150 houses in Denver. The 1893 depression ruined his thriving career. He remained in Denver for the next two years, even though new construction had come to a virtual standstill. By 1895, Lang was in severe financial difficulty, poor health, and suffering from progressive dementia brought on by depression. He left Denver in 1896 to spend time with a brother in Chicago. His life ended when he was hit by a train in August 1897.

Grinstead, Leigh A. Molly Brown's Capitol Hill Neighborhood. Denver, CO: Historic Denver, 1997. Print.

For more information about this neighborhood, the complete Historic Denver Guide is available from Historic Denver at www.historicdenver.org.

Now located at 1515 Race Street, the Milheim House stood across the street from the Molly Brown House for ninety-six years. In 1893, John and Mary Milheim purchased the land just prior to the Silver Crash.

In the early 1980s an oil firm purchased the property and invested $200,000 in its restoration, but the company eventually outgrew it and sold it to the Colorado State Employees Credit Union. The credit union hoped to build a bank at the southwest corner of 14th and Pennsylvania, but their efforts were unsuccessful. They demolished an apartment house on that corner and built a parking lot instead. They also considered destroying the Milheim House, but preservation organizations opposed it. Against the credit union’s wishes, the Denver Landmark Preservation Commission designated the house a landmark. The credit union then offered $40,000 to anyone who would move the house. Ralph Heronema and James Alleman accepted the offer and moved the structure, in one piece, to a vacant lot at Colfax and Race on September 15-16, 1989. It is the largest house move to date west of the Mississippi. The move averaged 1 mile an hour; trees were trimmed, power lines buried, and traffic signals temporarily relocated to accommodate it. When the house arrived by its new location, it remained in the middle of Race Street for a few weeks awaiting a foundation.

Preservationists always consider moving a building out of its original context to be a last resort. However, the new owners have done considerable work in caring for the property. They will never recoup their financial investment, although they feel the effort was well worth it.

Grinstead, Leigh A. Molly Brown's Capitol Hill Neighborhood. Denver, CO: Historic Denver, 1997. Print.

For more information about this neighborhood, the complete Historic Denver Guide is available from Historic Denver at www.historicdenver.org.

This mansion was the focal point of Denver society for many years. Originally the house had two addresses: The front-door address was 150 East 10th, but the Hills listed their home as 969 Sherman. Sherman Street leads directly to the state capitol, and the Hills craved association with political power.

Crawford Hill graduated from Brown University in 1883 and became a partner in his father’s Denver smelting business. Known as a Republican warhorse, he went on to manage the Denver Republican, an influential western paper. Hill also served as director of the Denver Museum of Natural History. In 1895 he married Louise Sneed, from an aristocratic Memphis family. Upon arriving in Denver, she found Hill’s mother, who had created the first social registry, to be the reigning queen of local society. Louise attacked Denver’s traditional lecture and chamber music events, claiming they were too somber, and began serving champagne at her luncheons and hosting Denver’s longest parties and balls, complete with champagne brunch at dawn. She also established the “Sacred Thirty-Six,” an elite group of Denver socialites. Although Louise was eventually acknowledged as the leader of Denver society, her mother-in-law considered her a shameless social climber. Louise and Molly Brown never hit it off either. Still, after Molly survived the 1912 sinking of the Titanic, the Sacred Thirty-Six held a luncheon at the Denver Country Club in honor of the “unsinkable” heroine. Crawford Hill died in 1922; Louise continued to rule the social scene until 1942. She moved to an apartment in the Brown Palace and sold the house in 1947. She died in 1955.

The mansion became the Denver Town Club, a Jewish social organization. In 1953 a swimming pool replaced the gardens. In 1989 the club disbanded and the building was sold. A classical statue of a nude woman holding lilies, which Louise had unveiled in her garden to open the social season, was sold to help pay for the house’s restoration. Haddon, Morgan & Foreman, P.C., received the Colorado Historical Society’s 1990 Stephen H. Hart Award for their restoration and rehabilitation of the building.

Grinstead, Leigh A. Molly Brown's Capitol Hill Neighborhood. Denver, CO: Historic Denver, 1997. Print.

For more information about this neighborhood, the complete Historic Denver Guide is available from Historic Denver at www.historicdenver.org.

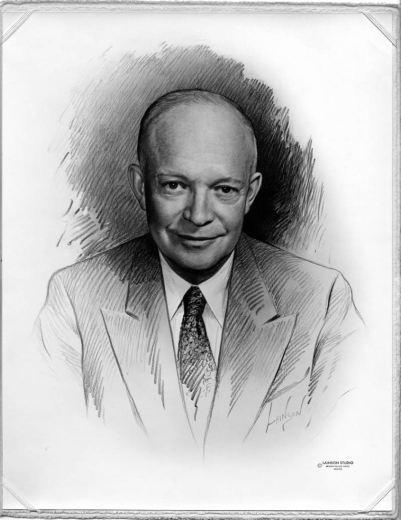

Mamie Doud Eisenhower, future first lady of the United States, grew up in the Capitol Hill Neighborhood. The Doud family home located at 750 Lafayette Street is a Denver Foursquare, which simply means that the design has four square rooms on the first and second floors. She was born November 14, 1896 in Boone, Iowa to parents John Sheldon and Elvira Matilda Carlson Doud. The Doud family moved to Cedar Rapids, Iowa in 1897. In 1905, John Doud decided to move the family to Colorado after making his fortune in the meat packing business. They first settled in Pueblo then Colorado Springs and finally Denver. The Doud Family was close knit, fun-loving and actively involved in their community. Mamie attended Denver Public Schools including Corona Elementary (now Dora Moore Elementary) and graduated from East High School. After high school, she attended Miss Wolcott’s, a private finishing school for the daughters of prominent families. Despite their efforts to remain an ordinary family, Mamie or “Miss Doud” frequently appeared in the Denver Post’s society pages.

Starting in 1910, each winter the Douds escaped the cold weather of Colorado for the warmer climate in San Antonio, Texas. It was here that Mamie was introduced to Second Lieutenant Dwight D. “Ike” Eisenhower in October 1915 at Fort Sam Houston. The couple had an instant attraction. Ike began his courtship of Mamie and proposed marriage on Valentine’s Day in 1916. The engagement ring was a miniature copy of his West Point ring, an amethyst set in gold. The Doud family was very fond of Ike, but Mamie’s father John had concerns about his daughter being an army wife. Despite her father’s concerns, Mamie was determined to marry Ike. They were married at the Doud family home at noon on July 1, 1916, on the same day that Ike received a promotion. Following the ceremony, the newlyweds took a ten day honeymoon that started in Colorado, then went to Abilene, Texas to visit Ike’s parents and ended in Manhattan, Kansas to visit Ike’s brother Milton.

After their marriage from 1916 to the beginning World War II, Mamie played the role of the army wife, moving her family from army post to army post across the United States and overseas. She would often come back to visit and stay with her parents at 750 Lafayette if she could not accompany Ike on assignment. During the Second World War, she lived alone in Washington D.C. while their son John was at West Point and Ike was serving his country. Mamie and Ike did not see each other for three years during the war, but kept in touch through letters and telegrams.

The Eisenhower’s had two sons, Doud “Little Icky” Dwight (born September 24, 1917) and John “Johnny” Sheldon Doud (born August 3, 1922). Doud Dwight died when he was three years old from scarlet fever. John Sheldon Doud graduated from West Point on D-Day in 1944 and married Barbara Jean Thompson in 1947. The couple had four children, Dwight David II, Barbara Ann, Susan Elaine and Mary Jean.

During the military years and throughout Ike’s presidency, the Eisenhower’s were known for their hospitality. Mamie was a sincere and warm person, who was a gracious and charming host. Mamie was a popular first lady during Eisenhower’s terms in office from 1953 to 1961. As first lady, Mamie had a busy schedule making appearances for various organizations and causes. She was also prolific in her correspondence with the American people. She believed that if someone took the time to write her that she would return the favor. The Eisenhower’s kept in contact with many friends in Colorado including Mr. and Mrs. Dan Thornton. Governor Dan Thornton was an ardent advocate of President Eisenhower, who campaigned for his election to the U.S. Presidency and nominated him at the Republican National Convention in 1952.

After President Eisenhower’s retirement, they retreated to their farm in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania that they had purchased in 1950 and restored. After Ike’s death in 1969, Mamie continued to live on the farm until she suffered a stroke on September 25, 1979 and was rushed to Walter Reed Hospital. She died at the hospital on November 1, 1979.

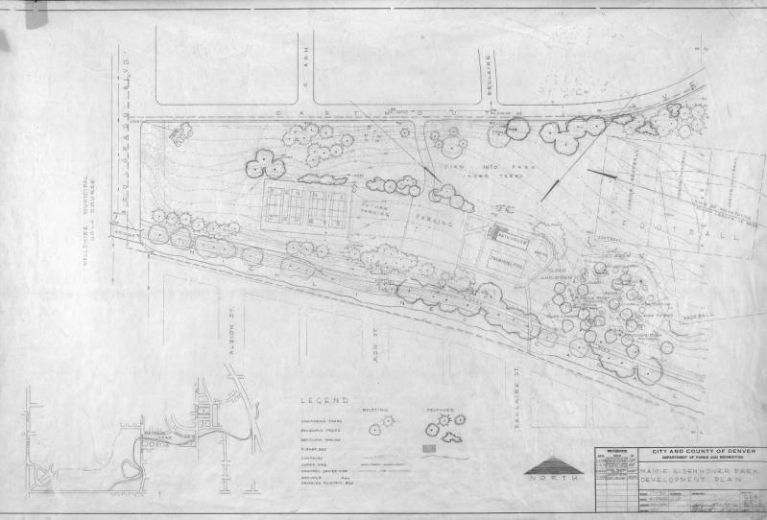

Cheesman Park in the heart of the Capitol Hill neighborhood is located between Humboldt Street on the west, Race Street and the Denver Botanic Gardens on the east, 13th Avenue on the north and 8th Avenue on the south. The original park plan was designed in 1898 by Denver’s landscape architect Reinhard Schuetze. Schuetze’s plan included a figure 8 roadway, a pavilion and reflecting pool and trees outlining the park. Although Schuetze died in 1910, his predecessor S.R. DeBoer completed the park utilizing most of his plan. The park constructed between 1900 and 1910 is an 80.7 acre rectangle, which features the neoclassical pavilion and a Japanese garden.

Originally the site served as Denver’s first cemetery, Mount Prospect. William Larimer and William Clancey established the cemetery during the winter of 1858 to 1859. It was located on an old Arapahoe Indian burial ground. Jack O'Neill, a victim of a gunfight, was the first burial on March 30, 1859. The cemetery was eventually divided into sections for Roman Catholic burials (Mount Calvary), Masonic and Improved Order of Odd Fellows, Jewish (Hebrew Burying and Prayer Ground) and Mount Prospect or Prospect Hill. Mount Prospect, later called City Cemetery, had areas set aside for burials of paupers, Chinese, and members of the Grand Army of the Republic, a Civil War Union veterans organization.

In 1872 the City of Denver applied to Congress for a title to the land. On November 15, 1873, Denver gained ownership and Mount Prospect became City Cemetery. However, Riverside Cemetery opened in 1876 and burials in City Cemetery declined. Shortly after, Colorado Senator Henry Moore Teller convinced Congress to allow the cemetery to be converted into a park. On January 25, 1890, Congress granted his wish and ordered the city to vacate the property. Teller then renamed the property Congress Park in honor of the act.

In 1893 burials were ordered stopped and 788 bodies were removed to Riverside Cemetery. In August 1893 the Denver Park Commission gave notice that families had 90 days to remove their loved ones' remains and that after that time no bodies were to be removed as the entire area would be planted in grass. About 4,200 bodies from City Cemetery remain beneath the sod of Cheesman Park.

Mount Calvary was the Roman Catholic section of Mount Prospect and later City Cemetery. In 1890, when Denver was granted permission to use the cemetery lands for a park, the Diocese of Denver secured an injunction preventing enforcement of the order against their property. The last burial in Mount Calvary was in 1908. In 1891, Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Wheat Ridge opened and many of the bodies from Mount Calvary were removed there. In 1950, the remaining 8,600 bodies were removed to Mount Olivet. Today this is the site of the Denver Botanic Gardens.

The Jewish section was known as Hebrew Burying and Prayer Ground. The local Jewish congregations did not hold title to their section and were not able to prevent the closure of the cemetery. In 1896, the Hebrew Cemetery Association purchased a section known as Emanuel in Riverside Cemetery. In 1911, Congregation Emanuel purchased 15 acres within Fairmount Cemetery, also called Emanuel. In 1923, the Jewish Cemetery Committee reported that removals from the Hebrew Burying and Prayer Ground had been completed.

In 1907, the park was renamed Cheesman Park by the Denver City Council to commemorate the donation by the Walter Cheesman family to build the Cheesman Memorial Pavilion. The pavilion, which is made of Colorado Yule marble, has served as a picnic spot and art venue for many generations of Denver residents.

For the most part the park has remained true to its original design. It remains one of the last city parks in the country where cars are permitted to travel throughout the grounds. In the last 20 years, local organizations, residents and city officials have worked to try to control traffic issues within the park to make sure that there is a balance between the needs of the neighborhood and the public. The park has been recognized on the National Register of Historic Places as part of Denver’s historic park and parkway system. It is also known locally as one of Denver’s most haunted places, due to the unclaimed souls that still remain under the park.

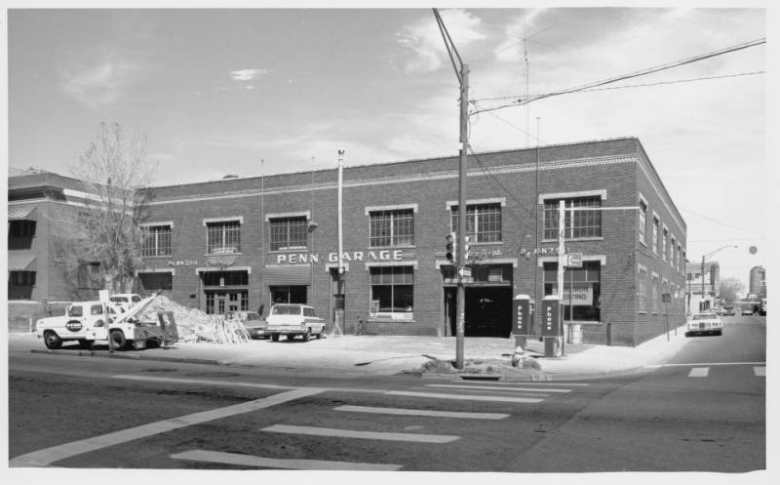

In Capitol Hill, structures such as the Penn Garage were built to house automobiles when recreational cars began to replace the horse and carriage. Wealthier families in the neighborhood stored their automobiles at the Penn Garage, including Molly Brown, who kept her Fritchle 100-mile Electric here.

This vehicle was one of the most expensive and elaborate cars of its day. Oliver Fritchle opened his electric car company in Denver in 1904, and by 1910 moved the factory to the building now known as Mammoth Gardens, at Colfax and Clarkson. The company handmade probably no more than 500 cars. It produced its own axles, steering parts, motors, controllers, and batteries, and even had its own sewing department. Its employees were recruited from old carriage manufacturing companies.

The 1917 invention of the self-starter for gas engines signaled the decline of electric automobiles such as the Fritchle. Today one can see quite possibly the last surviving example of a Denver-manufactured automobile, and an example of what Molly Brown’s car looked like, at the Colorado History Museum.

The Penn Garage has remained a Capitol Hill landmark and serviced automobiles for more than seventy years. In early 1997, it was purchased and renovated into lofts. Other commercial garages throughout Capitol Hill were built in a similar style and have the same red and blond brick and window patterns.

Grinstead, Leigh A. Molly Brown's Capitol Hill Neighborhood. Denver, CO: Historic Denver, 1997. Print.

For more information about this neighborhood, the complete Historic Denver Guide is available from Historic Denver at www.historicdenver.org.

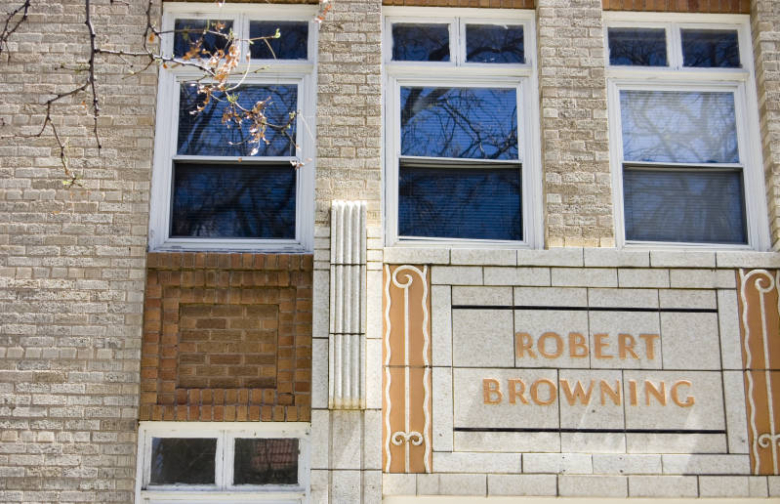

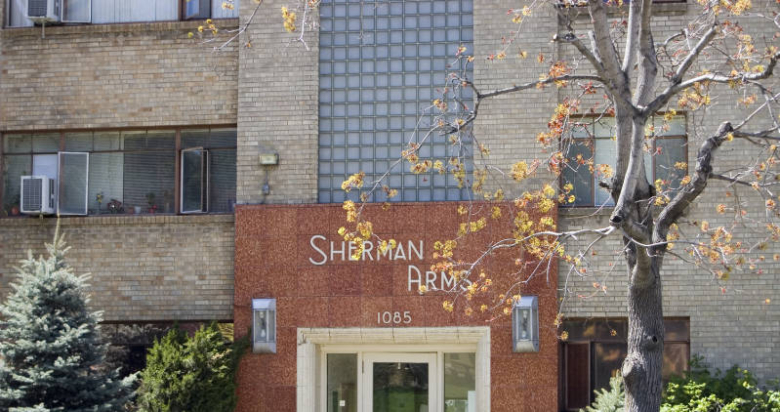

The Sherman Historic District in the Capitol Hill Neighborhood was listed on the National Historic Register of Historic Places in 2004. The district consists of three-story brick apartments with terra cotta door surrounds and trim on the 1000 block of Sherman between 10th and 11th Avenues. Locally the apartment buildings are known as “Poet's Row” because they are named after literary figures. All of the apartment buildings on the block are rectangular without inner courtyards and represent twentieth-century modern designs utilizing features from Art Deco, Art Moderne, and International styles. They also share a view of the Denver Capitol Building, which is two blocks north on Sherman Street. The origin of the Poet's Row name is not known, but the main architect for the historic district, Charles Strong was a lover of literature and might have been the inspiration for the building names.

1001 Sherman Street

Architect Andrew Brundel Willison designed this apartment building originally named Casa Bonita in 1929. The design is a mixture of modernist and Spanish colonial revival elements. In the 1930s, the building was renamed to Robert Frost after the American Poet who lived from March 26, 1874 to January 29, 1963. The original name “Casa Bonita” can still be seen in an interior bay above an arched terra cotta light surround.

1010 Sherman Street

The Thomas Carlyle, built in 1936 by architect Charles D. Strong, is similar with a few differences to the James Russell Lowell. It features Art Deco and Art Moderne elements. The building was named for Thomas Carlyle, a Scottish satirical writer, essayist, historian and teacher who lived from December 4, 1795 to February 5, 1881.

1015 Sherman Street

Originally named the Constellation, the Emily Dickinson was built in 1956 by an unknown architect. It is a subdued International style building. The building was named after Emily Elizabeth Dickinson, who was an American Poet who lived from December 10, 1830 to May 15, 1886.

1020 Sherman Street

The first building to be named after a literary figure, the James Russell Lowell was built in 1936 by architect Charles D. Strong. The style is Twentieth-century Modern and Art Deco. James Russell Lowell was a poet, editor, critic and diplomat that lived from February 22, 1819 to August 12, 1891.

1025 Sherman Street

In 1931, the second apartment building originally named the Casa La Vista was built and is attributed to architect Andrew B. Willison. The design is the same as the Casa Bonita with modern and Spanish colonial revival elements. The building was later renamed the Louisa May Alcott, after the American novelist who lived from November 29, 1832 to March 6, 1888.

1035 Sherman Street

The Mark Twain Building, built in 1937 by architect Charles D. Strong, features Art Deco and Art Moderne design. The Twain is more modern than the Browning which was built the same year and is the only building to feature an off center entry and rounded corners. The Mark Twain was named after Samuel Langhorne Clemens know by his pen name Mark Twain. Twain was an American author and humorist who lived from November 30, 1835 to April 21, 1910.

1045 Sherman Street

Built in 1938 by architect Charles B. Strong, the Nathaniel Hawthorne has Art Deco and Art Moderne elements that are similar to the Twain and features a centered entry with an oval overhang. Hawthorne was an American novelist and short story writer who lived from July 4, 1804 to May 19, 1864.

1055 Sherman Street

Named after the American writer Eugene Field, this apartment building was built in 1939 by architect Charles D. Strong. It features Art Deco and Art Moderne elements. Eugene Field lived from September 2, 1850 to November 4, 1895 and is best known for his essays and children’s poetry. Field lived in Denver from 1881 to 1883 and served as managing editor, news editor and poet of the Denver Tribune. When the four room house that he lived in at 315 West Colfax was in danger of being condemned in the late 1920’s, Margaret “Molly” Tobin Brown stepped in and bought the house to make it a memorial to Field. The house was moved to Washington Park in 1930 and served as a branch of the Denver Public Library for more than 40 years. Washington Park has a statue by Mabel Landrum Torrey (1918) that features the characters of the poem “Wynken, Blynken and Nod” that currently resides next to the Field House. A current Denver Public Library branch about a ½ mile from the park is also named after Field.

1075 Sherman Street

The Panama Apartments were built in 1942 by architect Charles D. Strong. The design reflects subdued Art Deco and Art Moderne elements that were typical of the World War II era. The building features an I-shaped plan and does not feature the name of a literary figure.

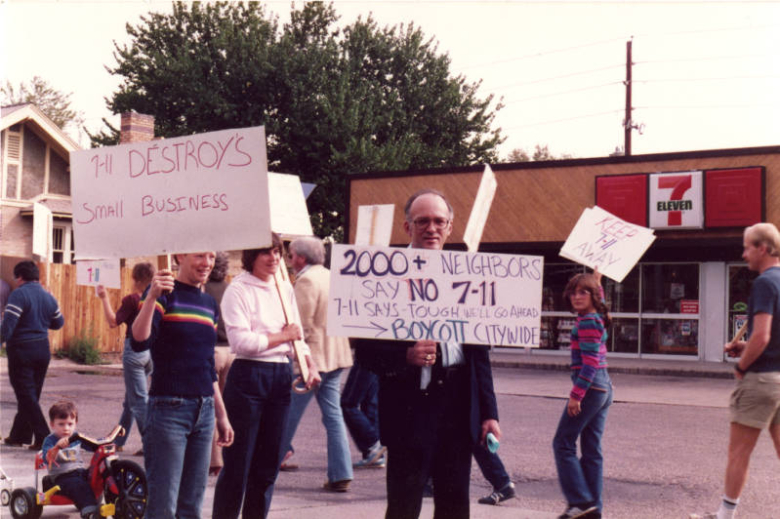

CHUN’s beginnings lay rooted in the desire to improve the Capitol Hill community. In 1969, a group of young Capitol Hill residents took a hard look at what was happening to their neighborhood in light of the urban flight and civic indifference, and decided something had to be done to stem further deterioration and disrespect of this historic but tarnished and neglected center city jewel. As community organizers they were a talented and experienced cadre. Many came from the ranks of the turbulent 60s protest generation. Their initial grass-roots resistance was to stand in opposition to the city’s plan to add more invasive and divisive one-way streets through the Capitol Hill neighborhoods (specifically 11th and 12th avenues). Reverend Bob Musil of Warren Methodist Church organized the concerned neighbors to fight the proposed conversion of East 11th and 12th Avenues into one-way streets. The group was successful in this endeavor.

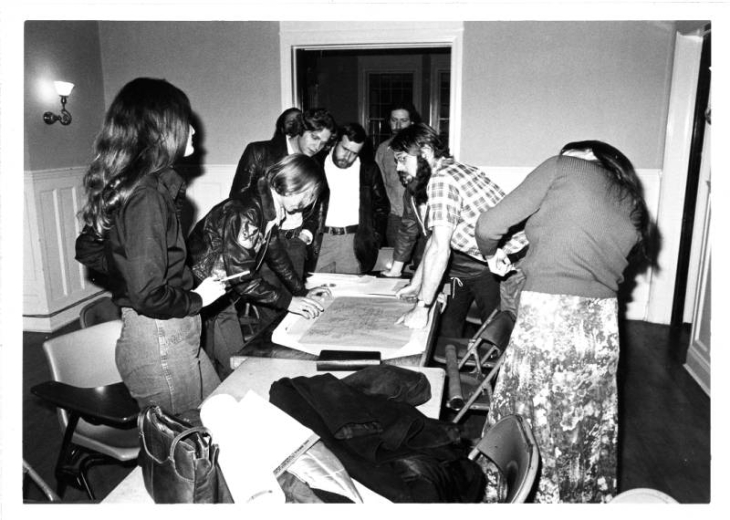

Encouraged by this success, the Capitol Hill Congress evolved, later to become Capitol Hill United Neighborhoods. From their first victory, the organization began to address issues of land use, zoning, housing and transportation. A more formal organizational structure was instituted and the geographical boundaries were expanded to their present limits (from 1st to 22nd Avenues and Broadway to Colorado Boulevard).

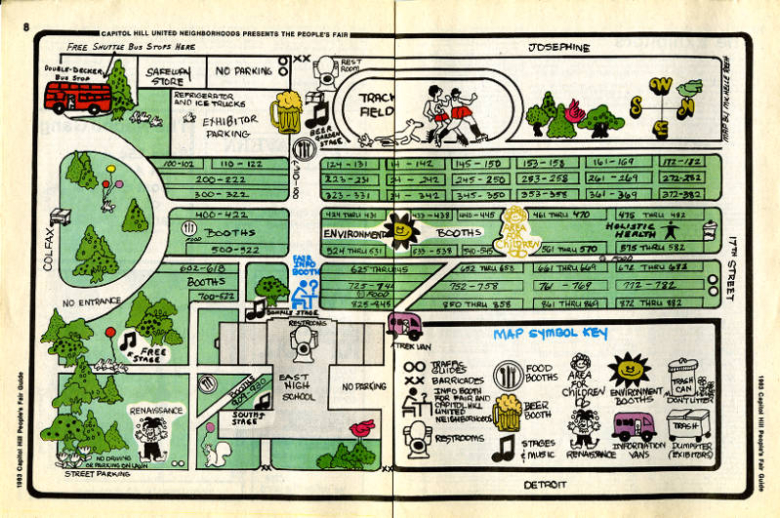

In 1974, CHUN agreed to take responsibility for running a relatively modest event called the Capitol Hill People’s Fair, which had been coordinated by the Police Storefront & Community Services Committee. Under the direction of CHUN, the People’s Fair has become a citywide gala event, drawing more than 250,000 people to its spring celebration of urban living. The People’s Fair has become the mainstay of CHUN’s financial existence, enabling a paid staff. Additionally, a percentage of the Fair profits are funneled back into the neighborhood through grants to community organizations. So far over $660,000 has been returned to the Capitol Hill community through the CHUN Grants Program. These funds have even helped to form new community-based organizations, such as Urban Peak and the Center for the People of Capitol Hill. Both began as programs funded solely by the People’s Fair, and both are now thriving, independent community organizations capable of funding their own programs.

In more recent years, CHUN has sponsored the Denver Police Department District 6 Halloween Event, the Haunted House Tour, the Victorian Holiday House Tour, and other fundraising parties and campaigns to boost CHUN’s financial base and support neighborhood causes.

In the late 1970s, CHUN continued to address issues of neighborhood concern, and grew in support and organization. In 1978, a half-time office staff person and half-time People’s Fair coordinator were hired. Opening an office in the Capitol Hill Community Center marked another sign of permanence and stability. Federally sponsored VISTA volunteers began to work under the direction of CHUN, addressing issues of transportation and the elderly, housing, the mentally ill, and economic development. In 1980, Meg Nagel was hired as the first professional Staff Coordinator. Currently, CHUN has a full-time staff including: Executive Director, Roger Armstrong; Assistant Director, Andrea Furness; Community Relations Manager, Cody Galloway; Operations Manager, Nicole Anderson; Groundskeeper, Andy Hina and part-time Staff Support, Jessica Yang.

Throughout the years, CHUN has been consistently working for the betterment of our Capitol Hill neighborhood. Zoning and liquor licensing, historic preservation, public safety, tree planting and homelessness and affordable housing issues constitute the bulk of CHUN’s current concerns. CHUN has gained and maintained recognition as a powerful organization supportive of neighborhood interests.

Growing from a handful of concerned citizens to an organization of over 800 members, CHUN derives its strength from its active membership – people involved in making our community a better place in which to live and work.

History supplied by Capitol Hill United Neighborhoods.

For more information please visit Capitol Hill United Neighborhoods.

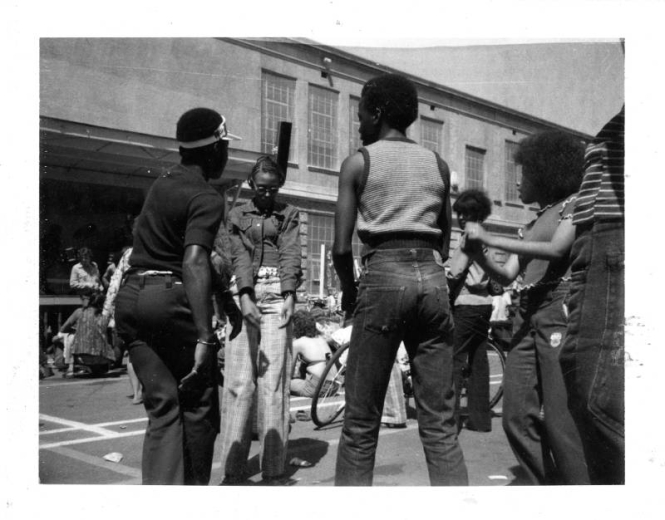

In 1969, a group of concerned citizens rallied to fight the proposed conversion of east 11th and 12th avenues into one-way streets. The citizens' victory over city planners marked the beginning of what is now known as Capitol Hill United Neighborhoods, Inc. or CHUN, one of Denver's oldest and largest neighborhood organizations. CHUN's boundaries extend from First to 22nd avenues and Broadway to Colorado Boulevard. In 1971, in order to forge more amicable relations between City Hall, the Denver Police Department, and residents of Capitol Hill, Denver Police Lt. Richard Alligood worked with community residents to create neighborhood get-together on the grounds of what was then Morey Junior High School. That first year, 2,000 people attended.

In 1974 CHUN assumed production of the People's Fair. By 1976 the Capitol Hill People's Fair had outgrown Morey's grounds. CHUN officials sought to move the Fair to Cheesman Park, but city officials and then-mayor William McNichols Jr. would not agree to that plan due to the city's anti-huckstering measure on city grounds. Shortly before the event, a compromise was reached between the city and CHUN to move the fair to the grounds of East High School. By 1987, ongoing success warranted moving the People's Fair to the current location in Civic Center Park, where it has continued to thrive.

The People's Fair remains a shining example of urban diversity and neighborhood pride. It is still a community-oriented volunteer event that benefits Capitol Hill nonprofit organizations. The 300-some volunteers and 250,000 attendees create the magic of the People's Fair. Thirteen volunteer committees form the Steering Committee and work with the People's Fair Staff to jury arts and crafts, conduct an image contest, select entertainment, book the stages and turn Civic Center Park into Colorado's largest arts and crafts festival. The People's Fair features some 500 exhibitor and food booths.

Many people remember going to the Fair as a child and now take their own kids. 2009 marks the 38th anniversary of the People's Fair. In its 37-year run, the People's Fair has certainly grown. However, its role as a neighborhood unifying event still remains. Community resources continue to be showcased at the Fair. The Fair's founders would certainly be proud to know their brainchild has prospered while continuing its original intent.

History supplied by Capitol Hill United Neighborhoods.

For more information please visit Capitol Hill United Neighborhoods.