Barnum’s history is one of a quiet development over more than a century, although not for lack of a strong sense of community. In 1878, master showman P. T. Barnum purchased a tract of land on the western edge of Denver. Today this community of young first-generation and immigrant families welcomes newcomers from all over the world.

Barnum’s history is one of a quiet development over more than a century, although not for lack of a strong sense of community. As the journalist and historian Robert Autobee observes, Barnum’s struggle in the shadow of Denver’s often different priorities, and its corresponding sense of community occasioned by the city’s neglect of older neighborhoods, has shaped the neighborhood’s identity. Although the City of Denver draws a distinction between Barnum, bounded by Sixth Avenue (north), Federal Boulevard (east), Alameda (south), and Perry Street (west), and the contiguous and parallel Barnum West that extends to Sheridan Boulevard, residents of Denver’s other Westside neighborhoods have been known to appropriate Barnum’s scrappy reputation for themselves, and self-identify as residents. Or so some Barnum residents proudly say. Barnum, like Curtis Park, Park Hill, or Montclair, began as a nineteenth-century Denver suburb. But, unlike those neighborhoods, Barnum developed as a haven for working-class families. While never affluent, Barnum has been more prosperous than many other Westside Denver neighborhoods, a home for families of modest means, with a sense of pride and identity that has continued even as its faces have changed over the course of the twentieth century.

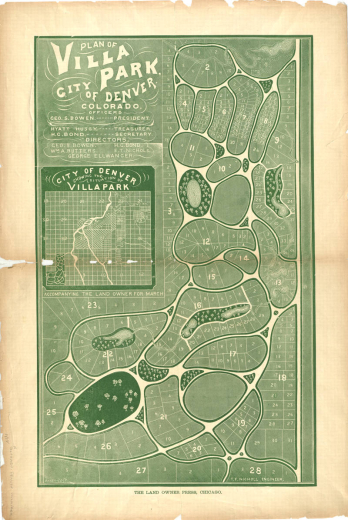

Like so many other American suburbs, Barnum began with a developer’s dream. In 1865, Daniel Witter bought 160 acres southwest of Denver, the first in a series of land deals in the development and promotion of Villa Park. Envisioned as a vast development with unique features such as curving streets, Witter’s dream of a home for Denver’s wealthy was never realized. The Denver Villa Park Association raised money for development, but lawsuits followed and the association was soon bankrupt. Lands were placed with a trustee, and on March 11, 1878, offered for sale. Less than two weeks later, on March 21, 1878, the American circus mogul Phineas T. Barnum bought 760 acres for just $11,000, and a few years later, the Barnum subdivision was platted.

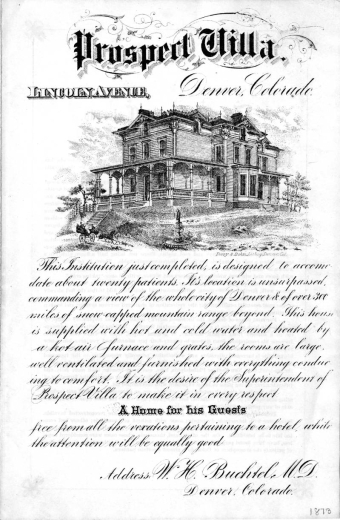

Barnum’s involvement with his namesake’s development has become part of Denver folklore, especially in the durable legend of the showman’s plan to establish a winter home for his circus in the city. In fact, Barnum never wintered his animals anywhere other than Connecticut or Florida, and the entertainment entrepreneur made just four documented trips to Colorado. Barnum sold as much of Barnum as possible before disposing of the remainder to his daughter, Helen Buchtel, for the price of one dollar. Ironically, much of Barnum’s initial development was a result of efforts by Helen, and her second husband, William Buchtel, who also served as mayor of an independent, incorporated Barnum established in 1887.

In many respects, the early and continued efforts to secure necessities like access to transportation, paved roads, and other basic amenities defined Barnum as a community devoted to improvement, one ready to direct its energy and, sometimes, its anger, at a city government perceived as uninterested in it and other Westside neighborhoods. A rail connection to Denver was finally established in 1893, but the service long remained inconvenient and a source of frustration. Perseverance and humor seemed essential to life in Barnum, and its sticky, poorly drained soils soon made mud a symbol of the community: “If you stick with Barnum,” went the community’s ode to itself and the muck on everyone’s shoes, “Barnum will stick with you.” Nevertheless, the neighborhood remained a destination for working-class families intent upon the measure of independence afforded by a modest home. Barnum was annexed to Denver in 1896, and its fortunes did improve as a result; new residents, businesses, and amenities followed. But the sense that each gain came as the result of a fight instilled both an enduring sense of resentment and a scrappy pride in home and community.

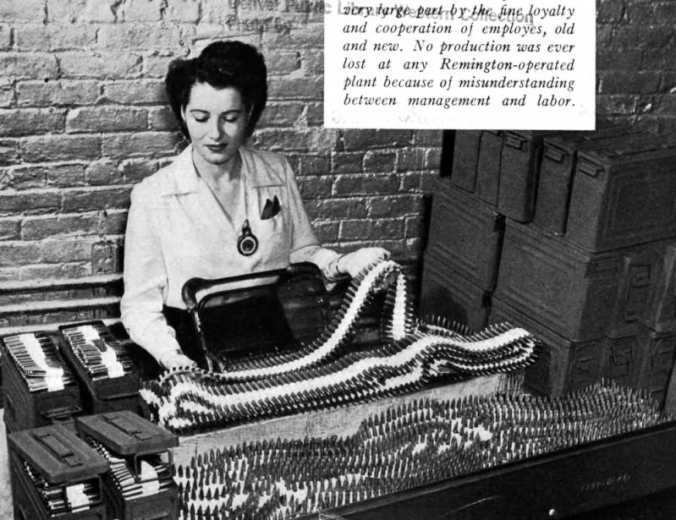

The Great Depression pressed hard in Barnum, like elsewhere in Denver and Colorado. The strains of unemployment and poverty subsided on the eve of World War II with a pivotal moment for Barnum and other neighborhoods: the establishment, in 1940, of the Denver Ordnance Plant. Manufacturing munitions for the war effort, workers in Denver, and those new to the city from elsewhere in the United States, found homes and community in Barnum and other Westside neighborhoods within an easy commute to the Ordnance Plant. In the years after World War II, continued suburbanization, and the development of a vast metropolitan Denver, led to a rapid boom in Barnum and posed a significant challenge for Barnum and its future as new Denver residents sought homes in the neighborhood.

But as more postwar families, many with the children who formed the baby boom, sought homes and a new level of comfort, developers created new communities removed from Denver’s urban center and its oldest suburban neighborhoods. Sixth Avenue afforded ready access to the suburban development to the west of Denver; many residents of Barnum, like others faced with the question of where to live, removed to the new suburbs. As one set of residents departed, others took their place. Beginning in the 1950s, large numbers of Hispanic residents, whether from long-established Colorado families relocating to jobs and opportunities in Denver or relatively new immigrants from Mexico, began to make Barnum a distinctly Hispanic neighborhood. In 1950, just ten percent of Barnum’s residents were Hispanic; three decades later, in 1980, a majority of its residents (50%) were Hispanic. Tensions emerged between newcomers and long-standing Barnum residents, but ultimately such conflict was muted, especially in comparison with those in other changing Denver neighborhoods, such as Park Hill. A common interest in quality of life the neighborhood afforded to new and older residents contributed to this easier transition, along with the development of community organizations, such as Concerned Citizens of Barnum, which mediated community conflicts and pressed neighborhood concerns at City Hall.

During the last third of the twentieth century, with its high rate of home ownership and household incomes significantly higher than other adjacent neighborhoods, Barnum became an island in Westside in decline. Housing values for many of the modest homes of Barnum remained higher than those of other neighborhoods, and the neighborhood continued to be desirable for those interested in comfortable homes at reasonable prices. In the mid-to-late 1970s, when the United States removed itself from wars in Southeast Asia, new immigrants from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos arrived in Barnum. Establishing themselves as residents before moving to other Denver suburbs, the more durable presence of these new immigrants remains as seen in the varied Asian American businesses of Federal Boulevard south of Sixth Avenue.

At the end of the twentieth century, durable residents of Barnum, like the redoubtable Nell Thompson, proudly found in their neighborhood something of a throwback to a quieter time. Interviewed in 1992, the 83-year-old Thompson likened Barnum to “living in a small town.” Thompson, a founder of Concerned Citizens for Barnum, worked for the neighborhood and its residents after the retirement of her husband, John, in 1964, helping to secure the addition of a senior center and pool to the Barnum Recreation Center, an amenity that a 1994 Denver Post article identified as the soul of the community. Ready action on behalf of the community continues. A rash of indecent exposure incidents near Barnum Elementary School during the 2002-2003 school year soon saw a neighborhood patrol established, complete with parents and grandparents armed with cell phones with cameras. Denver’s Rocky Mountain News reported that no incidents occurred after the establishment of the community patrols.

Today’s Barnum remains a neighborhood of families, now mostly Hispanic (some 75% [2000]) and of modest means (with an average household income of $41,185 [2000]). More than two-thirds of Barnum’s housing is owner-occupied, and the rate of Hispanic homeownership in the neighborhood is substantially higher (66.01% [2000]) than for the rest of Denver (49.11% [2000]). Poverty is no more common than elsewhere in Denver, and the portion of Barnum’s Hispanics living in poverty is substantially lower (15.35% [2000]) than the rate for Denver as a whole (22.47% [2000]). More Barnum residents earn less than 100% of Denver’s median income, but the portion of residents earning between 100 and 200% or more than 200% of the city’s median income are the same or similar to the rest of the city. Barnum is younger than the rest of Denver, with a higher percentage of children aged 17 or under, with fewer single-person households, and more families with children than Denver as a whole. Barnum remains a vibrant working class neighborhood, as it has been for more than a century.

Named after the famed P.T. Barnum of Ringling Brother’s and Barnum Bailey’s Circus, the Barnum neighborhood is located in West Denver. Legend has it that P.T. Barnum purchased the land to house his circus animals in the winter but this neighborhood was never used for that purpose. With 6th Avenue on the north, Alameda Ave on the south, Federal Boulevard on the east, and Perry Street on the west the Barnum neighborhood is square in shape.

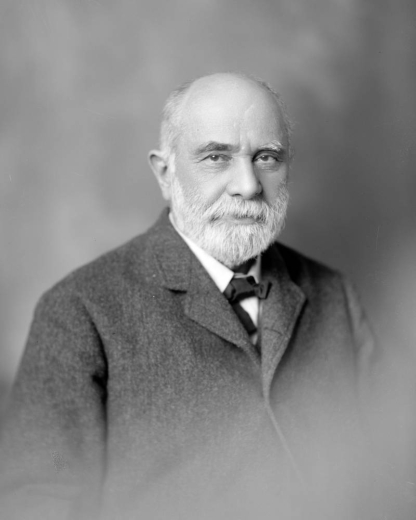

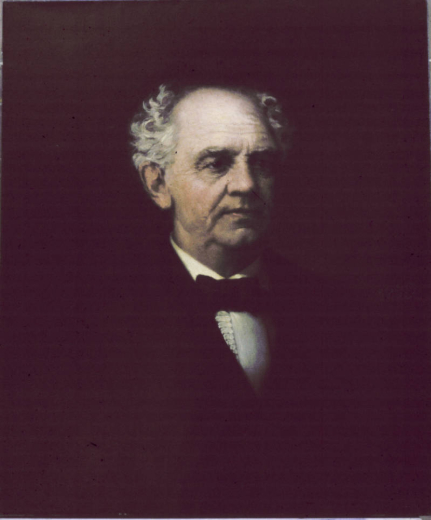

Phineas Taylor Barnum, self-proclaimed "Prince of Humbugs" was an American showman, entertainer, politician and businessman. Barnum became one of the most well known entertainers of the nineteenth century and the founder of what became the Ringling Bros. and Barnum and Bailey Circus.

Barnum was born July 5, 1810 in Bethel, Connecticut to Philo and Irene Taylor. In his twenties, Barnum owned several businesses, including a general store and a statewide lottery network. He was active in local politics and in 1829 founded the weekly paper, The Herald of Freedom. On November 8, 1829, Barnum married Charity Hallet. They had four daughters: Caroline Cornelia (1833-1911), Helen Maria (1840-1915), Frances Irena (1842-1844) and Pauline Taylor (1846-1877). Following Charity’s death in November 1873, Barnum married Nancy Fish, a woman 40 years his junior, on February 14, 1874 in London, England.

Barnum moved to New York City in 1834 to seek his fame in entertainment. His earliest ventures included a variety troupe called "Barnum's Grand Scientific and Musical Theater." His first success came in 1842 when he purchased the Scudder's American Museum, soon renamed the Barnum's American Museum. From 1842 to 1865, his museum was New York’s most popular attraction promoting 850,000 exhibits dedicated to the bizarre and unusual, including Feejee the mermaid, and little person Charles Sherwood Stratton aka General Tom Thumb. After bad investments bankrupted Barnum in the 1850s, he turned his energies to politics, lecturing and touring England and Europe with General Tom Thumb. Barnum served two terms in the Connecticut legislature (1865-1867) and was the mayor of Bridgeport in 1875. In 1867, he was nominated by the Republican Party for the United States Congress but was defeated. He also toured the country giving temperance lectures.

In 1871, Barnum returned to his life as a showman when he established P.T. Barnum's Grand Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan and Circus in Brooklyn. The circus found a permanent home in 1874 at the New York Hippodrome, later Madison Square Garden. In 1880, Barnum developed a partnership with James Bailey, who managed The Great London Show. Together the Barnum and London Circus, from 1887 known as the Barnum and Bailey Greatest Show on Earth, traveled the United States and Europe with 28 rail cars and more than 1,000 employees. After Barnum’s death in 1891 and Bailey’s death in 1906, their one-time rival, the Ringling Brothers, bought the famous circus. The shows were merged as the Ringling Bros. and Barnum and Bailey Combined Shows, The Greatest Show on Earth.

Barnum combined philanthropy and business throughout much of his later life. He made several donations to Tuft University and was appointed to the Board of Trustees prior to the university’s founding. Barnum also had investments throughout the country, including several in Colorado. Barnum’s interest in Colorado began in 1870, when he gave temperance speeches in Denver and Greeley (Union Colony), and soon he began to invest in local property. He owned land and rental property in Greeley, managed by the law firm Haynes, Dunning and Gipson. He also held shares in the Huerfano Cattle Company in Huerfano County and owned land, cattle and horses. Finally, Barnum owned several acres of land in Denver called Villa Park, now known as the Barnum, Barnum West, Villa Park and Valverde neighborhoods. Most of Barnum’s investments were disappointments. His Greeley tenants were constantly late with rent. One of his cattle company partners, David W. Sherwood, was a persistent debtor, always on the edge of bankruptcy. And Barnum’s Villa Park property needed repairs to the house, a fence and water to make it viable.

Many myths and legends exist about Barnum’s interest in Denver. He did not buy the Villa Park property to house his animals during the winter. He never intended to live in Denver. He visited Colorado in 1870, 1872, 1877 and 1890 to tend to his investments and see his daughter, Helen, who had created a huge family scandal when she left her husband, Samuel Henry Hurd, and their three children for Dr. William Harmon Buchtel. Helen and William married on March 2, 1871 in Indiana but as William had tuberculosis, they headed to Denver to seek a cure. While Barnum never truly embraced Buchtel, he continued to support Helen with his Colorado investments. The Buchtels lived on the Greeley property, ran a tuberculosis house called Prospect Villa Park, and assisted Barnum with Villa Park. The property was renamed the P.T. Barnum Subdivision of Denver in 1881, and Barnum transferred his holdings to Helen in 1884.

Today’s Barnum and Barnum West neighborhoods began to take shape in 1887, when incorporation papers were filed.

Barnum died on April 7, 1891 at his home in Bridgeport, Connecticut.

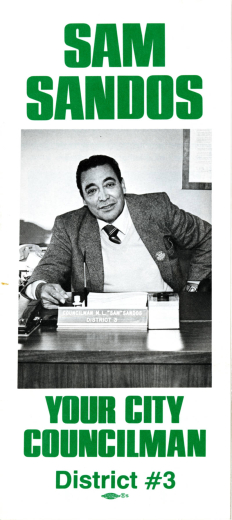

Manual "Sam" Sandos was born in Denver, Colorado on June 16, 1927, the son of a Greek coal miner and a Hispanic mother. Sam Sandos was a lifelong resident of Westside. In 1941, at the age of 14, he joined the 82nd Airborne division as a paratrooper (though lying about his age). During his combat in Europe, he was frequently decorated for heroism. He spent his final year in the service at Fort Carson, Colorado, where he successfully fought the loss of his legs to battlefield frostbite. While recuperating he met Ethel McCance, his wife of 41 years and mother of his two daughters and seven sons. Despite being a decorated U.S. Army veteran, Sam and Ethel Sandos were rejected as purchasers of a home in the Barnum neighborhood of Denver due to a covenant that prohibited Hispanics. They soon bought a home two blocks away where they raised their children as well as sheltered fourteen foster children over the course of forty years.

Sam Sandos was a lifetime member of the Parish of Our Lady of Presentation Church, where he established the Buddy Club for members of his local Knights of Columbus. He also served as an officer, founder or board member for organizations and groups such as Partners, Savio House, the Girls Clubs of America, the Hispanic Annual Salute, Samaritan House, Big Brothers, Police Athletic League, the Career Opportunity Center, Beaver Ranch, League of United Latin American Citizens, the G.I. Forum, Mass Media, and many others.

Sam Sandos started his professional life as a building and brick contractor, but it was his love of children that led him to community service and later into politics. By the early 1960s Sam was establishing Youth Centers for Westside kids. Mayor Currigan appointed him as a special assistant for Youth Affairs in the wake of the unrest that plagued the community at that time. In 1975 Sam Sandos was elected to the Denver City Council representing District 3 located on Denver's Westside. As the first Hispanic council member, Sam Sandos faced the task of building a bridge between Hispanic and white residents. During his 12 years and three terms in office, Sam Sandos was a leader in establishing the Auraria Higher Education Center and the Westside Health Center. His selfless efforts, devotion and grass roots activism brought his constituents and District 3 increased development as well as neighborhood awareness and interests.

Sam Sandos retired from the city council in 1987 due to declining health. He died on October 29, 1987 after a long illness and is survived by his wife Ethel; daughters Sheri Ortiz and Sandi Kaunalis; and sons Michael, Dave, Paul, Tim, Dan, Pat and Sean.

On the northeast corner of Cedar and South Knox Court in the Barnum Neighborhood there used to be a vacant lot with a “for sale” sign. But in the early 1990s, community activist April Crumley decided that it was the perfect location for a neighborhood park. The First Bank of Westland donated the land to use as a park, but it was discovered that the lot was a gas station from 1931 to 1941. The project soon came to a halt as the possibility of underground storage tanks disrupted the plans. Crumley called upon graduate students at the Colorado School of Mines to come and help her locate the tanks. By using electronic and magnetic feeds, the students located two tanks that were left in the ground by the gas station owner more than 50 years ago. After the bank helped out with the tank removal and cleanup, Crumley’s plan finally became a reality after receiving a small neighborhoods project grant that provided money for a sprinkler system and landscaping. In 1993, Denver Urban Gardens took the title to the park with the mission to develop and maintain the open space. The grand opening of the park was on May 13, 1995 and has been the location for Cedar Park Market and community celebrations.

Cedar Park features a stone walk with a shelter, picnic tables, and benches. The main attractions, with a nod to P.T. Barnum, are an elephant sculpture and decorative bronze cutouts by artist Calvin Farrow. The whimsical elephant sculpture is made out of rebar and chicken wire frame with a concrete exterior. Farrow even got the neighborhood children involved by letting them mix and apply the concrete to the elephant. The park today stands as a testament to the hard work and dedication of April Crumley. It provides a little piece of charm and peace to those in the Barnum neighborhood.

![A bust (3/4 view) portrait of Mrs. P. T. Barnum [Nancy Fish Barnum?]. She wears an ivory lace cap with a bow in the front and red flower on one side of her curled hair; a lace collar, circular locket with a bird painting on it and a black bodice with black lace trim. The background is dark green, brown and black. The painting itself is on rectangular linen canvas with four wood stretchers and is not framed.](/sites/history/files/styles/story/public/cdm_2008.jpg?itok=Ohf_T47u)